SUBSCRIBE ON

Act 1: Early History and Cultural Importance of condors

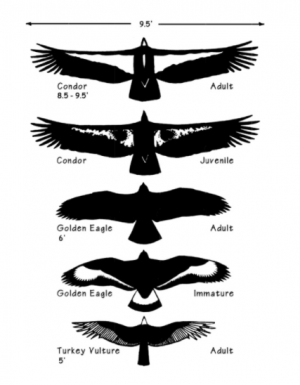

The free flying California condor is a rare sight in the wild, one which many people have not ever witnessed. But those lucky few who have described the experience as nothing less than awe-inspiring. It’s no wonder that this ancient species, with an impressive 9.5 ft wingspan of inky black plumage, commands the skies and holds a place in our minds and our hearts -- and why many are working incredibly hard to bring “thunderbird” back from the brink of extinction.

One such effort is being led by the Yurok tribe -- whose ancestral lands include the redwoods of Northern California -- because of their close spiritual and cultural connection to condors since time immemorial.

“[There are] ceremonies that we continue to dance to this day and tie to our fundamental reason for being as Yurok people, which is as world renewal people. We conduct these ceremonies, and actually condor in the beginning of time gave us the song that we sing. And, while we continue to sing the condor song and pray his prayer in our world renewal ceremonies and, while we’ve actually been able to get feathers from things like the condor feather repository, we still don't have condors in our skies carrying our prayers to the heavens.

- Tiana Williams-Claussen, Wildlife Department Director for the Yurok Tribe

Chairman Joe James of the Yurok Tribe performs a song in honor of the condor at a hearing of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., on February 27, 2019.

However, the Yurok are far from the only people to have a spiritual connection to the condor. Hundreds of miles away on what is now the border of Oregon and Idaho, the Nez Perce tribe, whose ancestral lands are in this region,also celebrate a connection to this mighty bird.

“Condors are part of the Nimiipuu creation stories and they're in the language, they're in place ---. In fact, [for] Joseph canyon, the Nimiipuu name for that translates roughly to the canyon where condors occur. And so we know that they were important to the Nimiipuu historically.”

- Angela Sondenaa, Wildlife Program Project Leader for the Nez Perce Tribe

Though it’s name can be misleading, the California condor is a native species of Oregon, and historically was found throughout a significant portion of the state, including Hells Canyon in Eastern Oregon near the border with Idaho. Known as North America’s deepest river gorge, Hells Canyon was carved out by the Snake River over millions of years, and is part of the ancestral homeland of the Nez Perce people. The canyon itself and the region around it also provide important habitat for a diverse variety of fish and wildlife species.

The Yurok and Nez Perce’s efforts to bring back condors to the Pacific Northwest skies are not only important for cultural reasons, but also vital because the species inhabits a key ecological niche that no other species on the landscape can fill.

“From an ecological perspective, they are a little bit of a missing link in the ecological system out there in that they have extremely powerful bills. They can tear into large game. In the terrestrial system, you can get bears opening up carcasses like that. But, in a lot of cases, we find areas of coastline where bears don't have access to the carcasses that wash up. So condors can actually do a lot of work towards cleaning up the landscape by opening those carcasses up and making them available to the broader scavenging community and really being one of the key recyclers in the whole process of bringing these carcasses back into the food chain.”

- Chris West, Yurok Tribe Condor Restoration Program Manager

To give a more specific example, let’s say a whale washes up on a beach. California condors have adaptations that allow them to start breaking up that carcass. Once the condors have started the work, other smaller scavengers like gulls and crabs come along to eat the remains. But without condors to do that work first, there isn't a predator large enough to start the process of breaking up the carcass, especially on some of the isolated areas along the Pacific Coast.

And that is a role they’ve played for a very long time.

In fact, condors, including all species and subspecies, have had a long presence in the Pacific Northwest dating back to well over 9,000 years ago, with some samples dating back over 30,000 years. Radiocarbon dating of ancient condor bones tell the story of these magnificent birds soaring over the mighty creatures of the Pleistocene era - which many of us think of as the Great Ice Age. When megafauna like the great wooly mammoth, mastodon, and bison lumbered across the land that is now the Western United States, large meat eating scavengers like condors and teratorns commanded the skies.

However, the condor’s wide-ranging dominance over Western skies slowly retreated. Archaeological evidence shows that during the middle of the Holocene, which is the current period of geological time beginning about 12,000 years ago, their range drastically plummeted to just around 200 miles from the Pacific Ocean.

There are two main related theories as to why the condor saw a huge reduction in range. The first is that terrestrial megafauna extinctions reduced the amount of carrion available for condors to scavenge, something that happened very gradually. As such, condors were able to adapt due to the long period over which this occurred, and also because there still remained enough large mammals to provide an adequate food source. Still, these inland megafauna extinctions would have had some impact, ultimately driving condors into a smaller range along the coast where marine food sources, like beached whales and sea lions, were still abundant.

The second theory is that drought during the mid-Holocene caused the massive reduction in condor’s habitat and range. This period of drought has been described as the most severe in the last 10,000 or even 100,000 years. A variety of mammals were especially vulnerable to changing conditions, which would have impacted the condor and their ability to scavenge. The only way the species could have survived was to live along the coast where drought impacts were mitigated by proximity to the ocean.

It is very possible that both a reduction of terrestrial food sources and climatic factors worked in conjunction to push the condor into its smaller range, one that would remain for the next several thousands of years.

By the time European explorers like Lewis and Clark arrived in the Pacific Northwest, the condor’s range was likely the Pacific Coastal areas from Canada to Mexico.

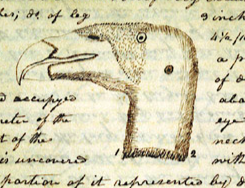

In February of 1806, Lewis noted the bird’s presence in Oregon when he remarked that the “buzzard of the Columbia” was likely the biggest bird in all of North America. But even their presence within that range was about to be reduced significantly.

Keep reading! Act 2: Decline of the Condor

Written and expanded chapters of the special audio program will be released each Thursday for the next month. Be sure to check back to learn more about the tumultuous history California condors endured, their fight to return and future efforts to recover this native and endangered species. Follow this story at oregonwild.org/shadowofthecondor

This project would not have been possible without grants from Mountain Rose Herbs and the Siletz Tribal Foundation. Special thanks to Jessica Riccardi and all our guests.