by Ethan Shaw

In this three-part series, we’ll explore what’s known about the grizzly bear in Oregon—its historical distribution and its extirpation—and muse on its potential life history in the Beaver State. First up: an overview of just where the griz once roamed.

Read Part 2: The Last Grizzlies of Oregon and Part 3: Ghosts of the Oregon Grizzly.

“The end of the bear as a physical presence coincides with the end of a human way of being at peace on the earth.”

—Paul Shepard, Encounters With Nature

|

| Grizzly tracks in Gates Of The Arctic National Park & Preserve |

Once upon a time, Oregon was grizzly country. Perhaps we should say that, once upon a time, Oregon was the dominion of the grizzly bear (or the co-dominion, anyway, shared with American Indian peoples), for few beasts anywhere hold such swaggering sway over their habitat as Ursus arctos horribilis. The great bear—he of the long claws and boxy head and silver-tipped coat—is gone now from the Beaver State (where once he undoubtedly tore up the lodges of more than one beaver family). It’s easy to imagine, though, that Oregon’s mountains and valleys are only just now getting accustomed to his absence. And, to paraphrase a famous quote by John Murray, those mountains and valleys seem just a bit smaller in stature given they’re now grizzly-free.

Not much has been written about the Oregon grizzly, so it seems appropriate—especially given the current National Park Service review of the feasibility of reintroducing grizzlies in the North Cascades to supplement their beleaguered population—to review what we know about the story.

I’ll say at the outset that this survey is woefully scant on the ethnographic side of things, reflecting almost exclusively on the slim Euro-American historical record. The indigenous perspective on the grizzly in Oregon deserves its own in-depth treatment, as there’s no question that the thousands of years informing it easily trump the gun-powdered century or so that white settlers meaningfully overlapped with the “Old Man in the Fur Coat” here. The Cayuse, Klamath, Molalla, Kalapuya, Umpqua, Chinook—these people shared salmon streams and huckleberry patches and oak groves for many generations with irascible grizzlies, while Euro-Americans considered the bear only rather incidentally as they shot him out.

|

| "The Old Man in the Fur Coat" (National Park Service) |

It’s also worth mentioning, here at the outset, that the grizzlies of California anchor a very rich lore (the definite inventory of which remains Tracy Storer and Lloyd Tevis, Jr.’s California Grizzly): their great heft, their arena battles with bulls (and, at least once, an African lion), their frequent encounters with miners, trappers, and mountain men—including Grizzly Adams, who ultimately toured the country (including Oregon) with a ragtag menagerie of wild-caught Golden State grizzlies and various other beasts1. Every once in awhile, that lore spills across the Oregon line—especially in the tale of Old Reelfoot, which we’ll get to—and the bioregional kinship that links the two states suggests the knowledge we’ve inherited about grizzlies in the northern Sierra Nevada, the Great Central Valley, the Klamaths, and the California Coast Ranges sheds some light on the ghost bears of Oregon, especially west of the Cascade Crest.

All that said, let’s kickoff this exploration of the silvertip in Oregon with a pertinent legend from the Molalla people of the eastern Willamette Valley and Cascade foothills.2 Off to create the world, they say, Coyote ran into Grizzly Bear near Mount Hood. Challenged to a fight, Coyote proposed a contest of swallowing red-hot rocks, then outwitted his opponent by downing some strawberries instead. The scalding stones that Grizzly consumed killed him, and Coyote, upon skinning the carcass, tossed the bear’s heart toward the country of the Molallas, thereby sanctifying their hunting grounds—and enshrining the grizzly bear in the indigenous mythology of Oregon.

The Grizzly’s Historical Oregon Range

|

| Vernon Bailey's map of the grizzly's historical distribution in Oregon, from his Mammals and Life Zones of Oregon (1936) |

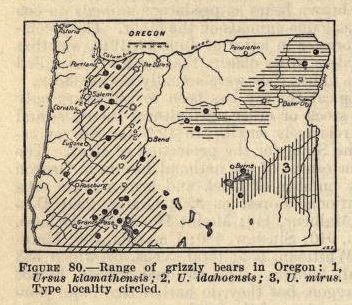

Our picture of the historical (that is, pre-contact) range of the grizzly bear in Oregon is not ironclad. Considered together, several maps made over the last century suggest the bear’s native geography in the state as well as some of the gaps and contradictions in our collective knowledge. On the earlier end of things—but, lamentably, not early enough to have been inked at a time when the silvertip occupied anything close to its original Oregon dominion—are C.H. Merriam’s hand-drawn 1922 map of grizzly distribution in the U.S. at that time; Ernest Thompson Seton’s map of the bear’s pre-contact range in all of North America, published in Lives of Game Animals (1926); and Vernon Bailey’s map of original Oregon grizzly country, from his 1936 monograph Mammals and Life Zones of Oregon.3

Seton’s map excludes much of Oregon from the grizzly’s native geography, save for the southern half or so. In Lewis and Clark Among the Grizzlies, Paul Schullery uses Seton’s map, the accounts of the Corps of Discovery, and some early Washington State records to suggest that most of Oregon north of the Klamaths (and southwestern Washington) was basically devoid of grizzlies, possibly because of dense indigenous populations in the greater Columbia Basin.4 This assertion—and Seton’s map—appears to fall somewhat short of the real picture.

Bailey’s survey of Euro-American grizzly observations (which also include a few nuggets of Indian knowledge) paints a substantially broader distribution. He shows grizzlies in the Klamaths, the western interior valleys, the Cascades, the Blue/Wallowa Mountains, and an arc of Southeast Oregon’s Great Basin and Snake River Plain. In a 2002 paper in Conservation Biology, David J. Mattson and Troy Merrill produced a map series depicting grizzly-bear range in the lower 48 circa 1850, 1920, and 1970, an effort that delivers perhaps the best available chart of Oregon’s original grizzly distribution.5 It agrees closely with Bailey’s 1936 map.

(Bailey, following the intricate, rather wacky, and now-obsolete taxonomic scheme C. H. Merriam proposed for the North American grizzly in 1918, referred to three subspecies in Oregon: the Klamath grizzly, U. klamathensis, of the Cascades, Klamaths, and Pacific Slope valleys; the Idaho grizzly, U. idahoensis, of the Blue/Wallowa Mountains; and the Yellowstone Park grizzly, U. mirus, of the Great Basin ranges and the Snake River Valley of southeastern Oregon. Modern taxonomists lump all these supposed races (and nearly all the rest of Merriam’s 80-odd varieties) as one subspecies of brown bear: U. a. horribilis.)

Grizzly bones have been uncovered in some wide-scattered corners of Oregon: a tooth from South Ice Cave near Newberry Volcano, a skull in the bed of Malheur Lake (along with those of bison and elk), a radius near the mouth of the Umpqua River. A grizzly limb bone discovered in Oregon Caves in the Klamath Mountains may be more than 50,000 years old, which would rank among the earliest brown-bear fossils found in North America.6 The caves also show a number of scratch marks thought to have been made by the claws of bears.

Grizzlies in the Western Valleys

As late as the first half of the 19th century, grizzlies were still to be found in the Willamette Valley; they persisted somewhat longer, it seems, in the Umpqua and Rogue valleys to the south. In these lowlands, Oregon grizzlies inhabited similar habitats to their counterparts in California (and, to a lesser extent, the Southwest): mosaics of prairie, oak savannas and parklands, riverine gallery forests, marshes, swamps, and heavier foothill woodlands.

In Bailey’s review, he mentions reports of “extremely ferocious” grizzlies in the Willamette in the early 1810s, and he cites Charles Wilkes, who, when overnighting in Champoeq during his far-traveling expedition of the early 1840s, heard that grizzlies were well known in the area and “that their flesh was esteemed for food.”

A 1900 article in The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society7, documenting the “reminiscences” of 82-year-old Louis Labonte, mentions his observations of two grizzlies in French Prairie, “one of which was in connection with a hunting party one foggy morning”; these sightings probably happened in the early 1830s. The piece further suggests an archaic indigenous origin for a Chinook term for grizzly, eshayum (compared with the black bear, itch-hoot), and thus concludes “grizzlies were a well recognized species in the Willamette Valley during the period of Indian occupation.” (Many vintage Chinook dictionaries give the trade jargon’s moniker for grizzly as si-am.8)

The pioneering botanist David Douglas recorded a few rather dramatic observations of grizzlies as he trekked up the Willamette and then the Umpqua in 1826—partly in search of the sugar pine, the supersized cones of which had intrigued him9. At dusk on October 1, somewhere in the mid-Willamette, he came across a yellow-jacket nest that had been downed by bears; soon after, one of his party’s hunters, John Kennedy, saw a big grizzly enter a “small hummock of low brushwood” not far from Douglas. Given the failing light, the two left the bear alone. Several days later, near modern-day Albany, a grizzly chased Kennedy into an oak tree and tore at his clothes. By that time, incidentally, Douglas had acquired a sleeping robe made from grizzly hide.

|

| Meadows near Bulldog Rock in the Umpqua National Forest (Robin and Gerald Wisdom) |

A few weeks later, Douglas finally found his in situ sugar pine up on what’s now called Sugar Pine Ridge, on the margin of the Umpqua Valley just west of Roseburg. The following day, he tracked down a grizzly sow and her two cubs near his camp; they had accosted his American Indian guide while he had been torch-fishing the night before. Finding the grizzlies eating acorns in an oak grove, Douglas shot one of the young dead and wounded—mortally, he thought—the mother, who had reared on her hind legs at his approach. Douglas ended up paying his guide with the carcass of the grizzly cub; the Indian, he wrote, “seemed to lay great store by it.”

Coastal Bruins?

|

| A grizzly bear in Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve scavenges a washed-up baleen whale. Prior to their extirpation, California grizzlies also were known to feed on beached whales; the same may well have been true for coastal Oregon bears (National Park Service) |

Several vintage Euro-American sources claim the grizzly was basically absent from the Oregon Coast Range, at least north of the maritime Klamaths. Bailey’s and Seton’s maps depict the Pacific coast as grizzly-free. In The Natural History of Washington Territory & Oregon10—a report on 1853-1857 surveys exploring the Northern Pacific rail route between the Mississippi and the Pacific—George Gibbs notes that grizzlies (“white bears”) were numerous in the North Coast Ranges and the Klamaths of California, but that “[m]ore to the northward they become scarce near the coast. I have never heard of them on the Coast range between the Willamette and the sea.”

This certainly doesn’t mean grizzlies didn’t inhabit the Coast Range; in fact, as grizzly expert Doug Peacock told me, it would be quite surprising if they didn’t, at least to some extent, given how they prosper in the spruce-hemlock rainforests of coastal British Columbia and southeastern Alaska (and how they once prospered along California’s northern coast). There is that grizzly radius from the Umpqua estuary, discovered (along with black-bear remains) by R. Lee Lyman during excavations at an archaeological site.11 And while the heavy timber of these mountains might be generally better habitat for black bears, the Oregon Coast Range did offer some irresistible grizzly resources: historically prodigious salmon and steelhead runs; late-summer berries (salmonberry, thimbleberry, evergreen huckleberry, currants, gooseberries, salal, etc.); the lush herbaceous groundcover in the redcedar and alder swales of the mountains or the spruce-pine strand swamps of the coast; the grazing and rooting grounds of the scattered mountaintop balds; and the seafood riches of the beachwrack.

Coast Range grizzlies perhaps were harder to detect because of the environment or because of a naturally sparse population; or perhaps they simply died off earlier.

Sky Island Bears

Certainly among the more farflung corners of the grizzly’s Oregon empire was Steens Mountain, that great 10,000-foot fault-block whaleback marooned in the Great Basin steppe and semidesert. Grizzlies once inhabited the mountain’s aspen woods and glacier-plowed gulfs, which also—despite their isolation from other high-country habitat—used to shelter wolverines. Bailey writes:

|

| Grizzly bears used to roam the high country of Steens Mountain in southeastern Oregon. (Sarah West) |

In 1916 William F. Schnabel sent the Biological Survey some notes from an old Piute chief, Yakima Jim, who told him that long ago there were so many bears in the Steens Mountains that the Indians did not dare go into the mountains alone, but always two or more together. In 1896, when Merriam and the writer were first in the Steens Mountains, and since then, it has been impossible to learn of any trace of grizzly bears there, and they were probably killed out at an early date.

The grizzly skull retrieved from the Malheur Lake bed also attests to the silvertip’s use of this region. And grizzlies skirted southeastern Oregon’s semiarid plains elsewhere, too—around the Klamath Lakes and Swan Lake Valley, for example, as well as in the volcanic highlands east of the Cascade belt, including Newberry Volcano and Yamsay Mountain.

[1] Storer, Tracy I. and Lloyd P. Tevis, Jr. California Grizzly. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1955.

[3] Bailey, Vernon. The Mammals and Life Zones of Oregon. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1936.

[4] Schullery, Paul. Lewis and Clark Among the Grizzlies: Legend and Legacy in the American West. Gilford, Connecticut: Falcon, 2002.

[5] Mattson, David J. and Troy Merrill. “Extirpations of Grizzly Bears in the Contiguous United States, 1950-2000.” Conservation Biology 16 (2002): 1123-1136.

[7] Lyman, H.S. “Reminiscences of Louis Labonte.” The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 1 (1900): 169-188.

[9] Douglas, David. Journal Kept by David Douglas During His Travels in North America 1823-1827 Together With A Particular Description of Thirty-three Species of American Oaks and Eighteen Species of Pinus, With Appendices Containing a List of the Plants Introduced by Douglas and an Account of his Death in 1834. London: W. Wesley & Son, 1914.

[10] Suckley, George and James G. Cooper. The Natural History of Washington Territory and Oregon. New York: Balliere Brothers, 1860.

[11] Lyman, R. Lee. Prehistory of the Oregon Coast. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc., 2009.