Congress passed a spending bill last week after a month of negotiations produced a $1.3 trillion budget that will keep the federal government open for – gasp – a whole six months. The bill almost failed to become law after a whirlwind few hours that had President Trump threatening a veto, only to reverse himself, sign the bill, and pledge to never let another bill like it pass again.

While Trump didn’t like the bill, he wasn’t alone. A handful of prominent Democrats with eyes on a White House run voted against the spending package as well (including Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley). While they all had different reasons for their dislike of a bill that ramped up both military and domestic spending, it’s a fair bet that none of them were opposed to the so-called fire funding fix embedded in the legislation.

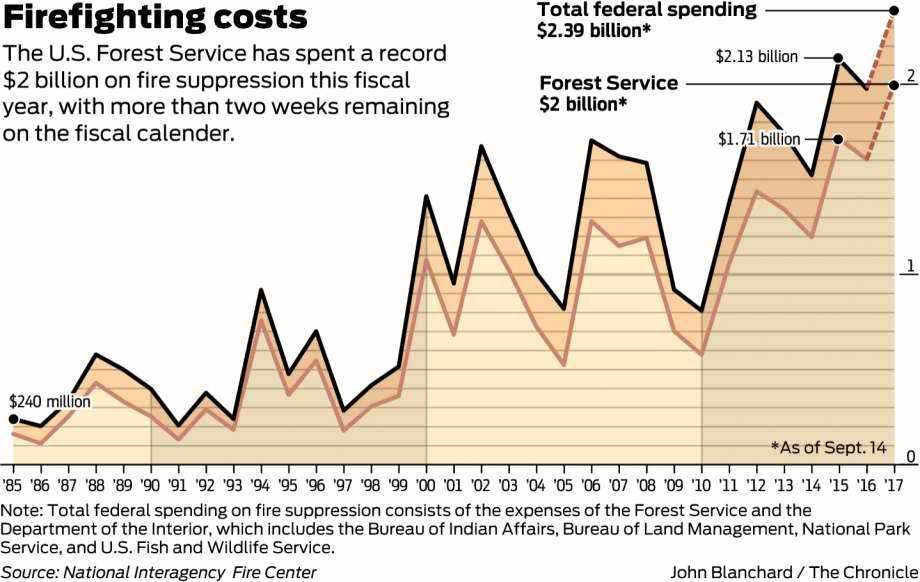

This fire funding “fix” has been touted by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, dozens of environmental organizations, and many in the timber industry. Over the last two decades, the United State Forest Service (and other land management agencies) has spent an increasing amount of money attempting to put out forest fires. In 2017, the feds spent $2.4 billion across the country on firefighters, air tankers, bulldozers, meals, supplies, encampments, and more. That’s a 10-fold increase from costs in the 1990s.

Those firefighting expenses have consistently eaten up more of the general Forest Service budget – a process termed “fire-borrowing” whereby the agency would essentially steal from itself to throw money at fire.

Surprisingly, “throwing money at fire” is not a far cry from the truth. While some resources are spent near communities to make homes more resilient to fire or to make last ditch efforts to keep flames from burning down homes or structures, a lot of the money is foolishly spent on attempting the near impossible – putting out large weather and wind-driven fires that are only truly extinguished when the first heavy rains of fall arrive.

Fire experts Dominick DellaSala and Timothy Ingalsbee make the point well:

“…large fires burn under hot, windy, and dry conditions when they are humanly impossible to put out and futile to even try. When we try to stop fires in those conditions, we might as well be throwing money out of air-tanker windows.”

The much lauded fire funding “fix” doesn’t actually fix the inherent flaws with our methods of fighting fire in the U.S. The bill allows the Forest Service to tap into a disaster fund if the cost of fire suppression exceeds the 10-year average cost of fighting fire ($1.4 billion). If costs exceed this already insanely high rate, the Forest Service can still spend ever more money from the disaster fund. The approach is a little schizophrenic. On the one hand, we are saying that fire is like any other natural disaster and should draw on emergency funds when disaster strikes. On the other hand, we are pretending that we can control (and even halt) fire if we just spend enough money.

Imagine if we applied this thinking to earthquakes. Instead of investing money in reinforcing our buildings and infrastructure, we just waited for the earth to start shaking and then spent billions to try and make the ground sit still.

Even though fire is a natural and essential part of our forests, it makes for an easy scapegoat (a bipartisan one at that). The GOP (and plenty of western Democrats who should know better) incessantly claim that the only reason fire is so bad is because environmentalists have halted all logging in our National Forests. It’s the old line that we must log the forest to save it. On the left, we hear doomsday scenarios linking ever bigger fires and ever longer fire seasons to climate change.

That OPB headline is patently ridiculous. However, there is some truth to both of these arguments but if we take either to the extreme we end up with rather confused policy when it comes to fire. In many places, our forests are out of whack. Typically, though, these forests are departed from historical conditions because we have logged all the big trees, set cattle loose on millions of acres to chew down native vegetation, and then suppressed the hell out of fire to the best of our ability. That has left plenty of forests that do need restoration.

In a much cited (and much ballyhooed) report by the Nature Conservancy and the United States Forest Service from 2015, the authors concluded that 11.8 million acres of forests on all land ownerships (public and private) east of the Oregon and Washington Cascades were in need of restoration due to abnormal fire risk. Policymakers and the timber industry have taken this number and run with it – logging it all being the preferred solution. But if you go beyond the catchy headline of the report, you see that active management (ie: cutting trees down) is only part of the prescription for restoring these lands. Just as needed, if not more necessary is for fire to be reintroduced and forests left alone to grow into older and more resilient forest.

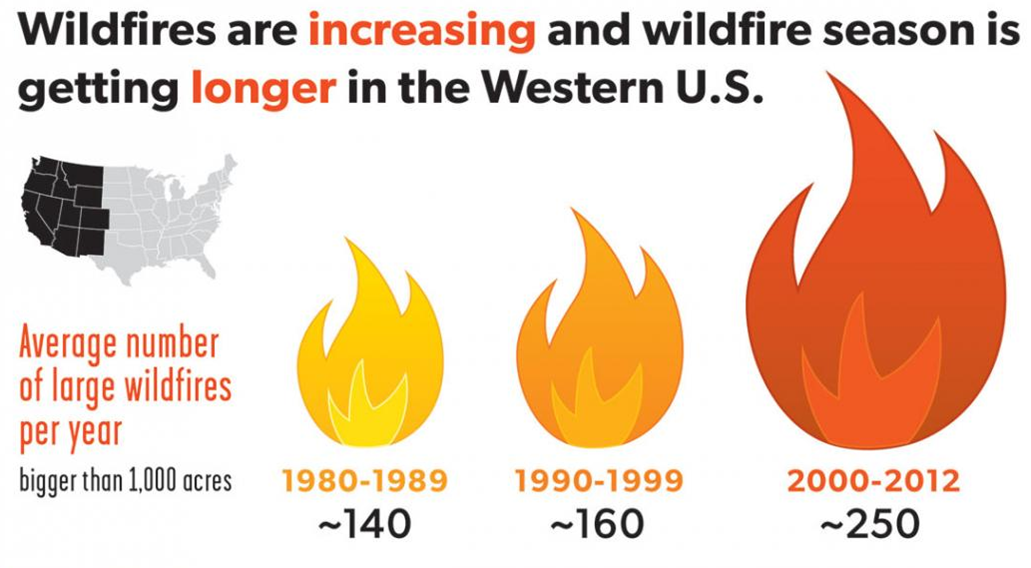

When it comes to climate change and forests, there is no doubt that hotter summers and potentially increased droughts are going to change fire behavior. Most like to cite numbers from the last 30 years that show a marked increase in the number of fires over 1,000 acres and the length of the fire season. The graphic here is from the Union of Concerned Scientists report on fire and climate change. And how can you not believe them – they are concerned!

Again, if we look a little deeper we see that the full truth is more complex. Over the last 30 years, fires have grown larger, but they haven’t burned any hotter. And, perhaps more importantly, they still aren’t burning at anywhere near the frequency and acreage that they did historically. We have a pretty large fire deficit in the Western U.S., largely driven by our dogged pursuit if extinguishing every fire we can.

So, how does the fire funding “fix” fit in to all of this?

The truth is, we don’t quite know yet. But, we can make some educated guesses. The reason for uncertainty, is that we have no idea how the Forest Service (continually under pressure from a logging industry and many state and local politicians from both sides of the aisle) is going to use the new fire funding source or the flexibility that will come with spending less of their core budget on fire.

Are they going to continue to fight fire the same way they always have? Certainly, the trend of firefighting spending does not suggest that fiscal responsibility and a brand new mindset are just around the corner. Though, there is some hope, as just this month the new lead official in charge of wildfire for the Forest Service in the Northwest had this to say on public radio:

“How do we stop saying, ‘we need more firefighters and we need more money,’ and we gotta throw more stuff at these fires."

Giller said prescribed burning can help thin forests and manage rangelands. He also said some fires should just be allowed to burn naturally. He said the keys to protect the public are “local notifications, evacuations, defensible space.”

While statements like these are refreshing and becoming more common within the agency, the predominant thinking still seems to be more in line with the message put out by the official Forest Service twitter account on the passage of the fire funding bill.

Those of us hoping that some of those saved dollars would go toward recreation and improved infrastructure may have to wait.

In the end, the fire funding “fix” holds some potential but it is only as good as the agency in charge of spending the money.