By Taylor Rudow, Oregon Wild intern

Next time you find yourself in the basin of Crater Lake, take a few moments to examine the underside of the rocks and driftwood found along the shoreline. With luck, you will unearth a rare specimen: the Mazama Newt. The Mazama Newt (Triturus granulosus mazamae), also known as the Crater Lake Newt, is endemic to Crater Lake. It is believed that hundreds of years ago, during an especially wet period, the Oregon Newt was able to find its way over the lip of the caldera and into Crater Lake. However, the caldera walls have served as a natural isolating mechanism, so no Oregon newts have been able to make the trek since the initial colonization. This separation has allowed the Mazama Newt to evolve into what is widely believed a unique subspecies.

The Mazama Newt is strikingly similar to other Oregon newts. Dark brown backs and tails allow them to successfully blend with the muddy logs and rocks where they spend most of their time. Inquisitive, round black eyes are constantly scanning their surroundings, and adorably small webbed feet dig feverously into the mud. However, when flipped on their backs, these newts are anything but camouflaged. It is also in this area that the two subspecies are finally distinguishable; Oregon newts have an immaculate orange-yellow underside, while the Mazama Newt’s belly is a much more moderate tone. That being said, without both species present for easy comparison, it is nearly impossible to delineate between the two through looks alone.

The Mazama Newt is strikingly similar to other Oregon newts. Dark brown backs and tails allow them to successfully blend with the muddy logs and rocks where they spend most of their time. Inquisitive, round black eyes are constantly scanning their surroundings, and adorably small webbed feet dig feverously into the mud. However, when flipped on their backs, these newts are anything but camouflaged. It is also in this area that the two subspecies are finally distinguishable; Oregon newts have an immaculate orange-yellow underside, while the Mazama Newt’s belly is a much more moderate tone. That being said, without both species present for easy comparison, it is nearly impossible to delineate between the two through looks alone.

It is their unseen differences that truly set the Mazama Newts apart from their Oregon relatives. Newts are the only land animal to contain tetrodotoxin (TTX), a potent neurotoxin produced as a defense against predation; the Mazama Newt is no exception. However, when the Mazama Newt colonized Crater Lake, they were met with a habitat free of fish and crayfish predators. Producing tetrodotoxin is extremely energy-intensive, so Mazama Newts produced less and less as they grew accustomed to their predator-free habitat. Today, Oregon newts produce 4000 times the toxin of the closely-related Mazama Newt.

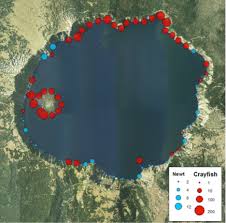

While the lack of toxin-production allowed the Mazama Newt to thrive undisturbed for hundreds of years, it is also the reason that these mesmerizing creatures are now facing extinction. In 1915, non-native crayfish were introduced into Crater Lake as a food source for (ironically) the non-native fish. Since then, crayfish populations have skyrocketed, causing the Mazama Newt, the Crayfish’s primary food source, to suffer. Due to their lack of toxins, the only defense Mazama Newts have against these predators is to attempt to stay out of their way. Today, crayfish occupy over 80 percent of the previously newt-dominated lakeshore. In contrast, newt populations are at an all-time low, and biologists worry that extinction may be inevitable.

Though efforts to save the newt are currently in effect, they have been largely unsuccessful. Our lack of knowledge is striking in this regard; we don’t even know enough about the Mazama newt to save them. Much of their life histories in Crater Lake are a mystery to us. Once again, we are watching an animal that we barely know disappear before our eyes. It is important that we strive to save the few remaining Mazama Newts and they find ways to reclaim the pristine Crater Lake they call home. But most importantly, it is important that we learn from our mistakes, so that species will not suffer the same fate as the Mazama Newts in the future.

to save the newt are currently in effect, they have been largely unsuccessful. Our lack of knowledge is striking in this regard; we don’t even know enough about the Mazama newt to save them. Much of their life histories in Crater Lake are a mystery to us. Once again, we are watching an animal that we barely know disappear before our eyes. It is important that we strive to save the few remaining Mazama Newts and they find ways to reclaim the pristine Crater Lake they call home. But most importantly, it is important that we learn from our mistakes, so that species will not suffer the same fate as the Mazama Newts in the future.