by Robert Bailey, President, Elakha Alliance Board of Directors

A perfect storm is pounding the foundation of Oregon’s nearshore seascape, battering the web of complex relationships on which marine life depends and on which commercial and recreational ocean fisheries rely. Underwater photos, biologist surveys, fishermen input, and diver reports tell of a kelp ecosystem in peril. Photos show purple sea urchins, and not much more, covering the rocks where kelp and other seaweeds once grew. These urchins have eaten all the kelp, eliminating this valuable habitat and its enormous biological productivity.

The consumption of kelp by urchins is a natural phenomenon, but predators such as sunflower sea stars and sea otters have historically provided a key check to this prolific herbivore. However, the recent die-off of sea stars from a mysterious wasting disease; a "blob" of warm ocean water that inhibits the growth of kelp, and a massive “recruitment” of baby sea urchins in 2014 has resulted in accelerated kelp losses.

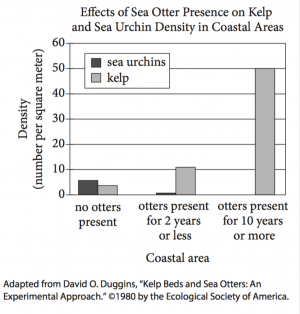

The term resiliency is used by ecologists to describe ecosystems with intact native biodiversity that can persist through change. In many cases, resiliency is about redundancy. While sea stars enhance the health of Oregon’s kelp ecosystem, the voracious sea otter was the other key to flourishing kelp.

The otter’s lush fur spelled their demise at the hands of market hunters. For more than 150 years they have been functionally extinct in Oregon – representing the earliest loss of a keystone species in the state. For decades, the ecological effects of the removal of sea otters were unnoticed in Oregon and much of the West Coast. Their absence was masked by the sea star’s appetite for sea urchins, especially the many-armed sunstars in deeper waters beyond the purple and orange “starfish” familiar in tidepools. (sunflower sea star pic)

Today, however, neither sea otters nor sea stars are present to control the plague of seaweed-eating purple sea urchins. Ominously, after polishing off available kelp, these “cockroaches of the sea” go into a state of suspended animation and wait, sometimes for decades, for their next seaweed meal. Between these waiting predators and influx of warmer ocean water, young kelp has no chance to grow.

Coastal communities such as Port Orford are considering ways to remove purple sea urchins and give kelp a chance to return. Studies in Haida Gwaii, off the coast of British Columbia, show that kelp and other seaweeds return quickly when urchins are removed. Evidence throughout the Pacific coast repeatedly demonstrates that sea otters will be key to any long-term solution to restore and protect Oregon’s kelp ecosystem.

The Elakha Alliance, named for a coastal Indian word for sea otter, is an Oregon non-profit organization whose mission is to restore sea otters to the Oregon coast because of their crucial role in sustaining a productive marine ecosystem.

However, to avoid putting the cart before the horse, Elakha Alliance is researching needed information, conducting a third party science-based feasibility study, a third party economic impact assessment, and building partnerships with other ocean users, wildlife agencies, university researchers, and coastal communities.

Sea otters are a long-term strategy to protect Oregon’s marine environment, not a quick fix. Even after animals again take up residence, it will take time to address urchin populations, restore the ecological balance, and enable the ecosystem to recover.

While under water and relatively out of sight, Oregon’s nearshore marine ecosystem needs help. Returning sea otters to their former home in Oregon will provide that long-term help. While the return of sea otters will create overall benefits to Oregon’s coastal communities, some sectors such as commercial crabbing and sea urchin harvest may experience negative impacts. The Alliance is committed to working with these ocean users to assess and reduce or avoid negative impacts. The Alliance is also working with the community in Port Orford to find short-term solutions to invasion of sea urchins and loss of kelp beds.

How can you learn more about our work?

To learn more about the Elakha Alliance please visit www.elakhaalliance.org and explore sea otter science, indigenous perspectives, our vision, and plan. Also, explore our podcast archive containing over 10 episodes with leading experts on the ecological and cultural dimensions of sea otters, kelp and other associated marine life.

What is our most important need now? We are seeking support to fully fund a third party economic impact assessment to analyze and address valid concerns held by various commercial shellfish stakeholders. Thank you for your support!

petportraitsbyedi.com

www.meredithlagerman.com

'

'