By Phillip Brown

What is now the northeast corner of Oregon has been a confluence of natural wonders since long before it was called Wallowa County. The Wallowa Mountains, themselves once home to coral reefs and later shaped by massive glaciers, stand tall above Hell’s Canyon, the deepest river-carved gorge in North America. The Zumwalt Prairie, one of the most intact grassland prairies in the United States, lies nearly encircled by the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest including the iconic Eagle Cap Wilderness and unprotected areas just as wild.

In recent years, Wallowa County has become home to another intriguing contrast as the once-extirpated gray wolf (Canis lupis) returns to its former homeland, within howling distance of the introduced livestock, ranchers, retirees, artists, loggers, tree-huggers, and all of the others who now call Oregon home.

To increase awareness and understanding of these carnivores-come-home – and the issues that surround them - Oregon Wild recently led the sixth annual Wolf Rendezvous, a four-day outdoor excursion just outside of Joseph, Oregon.

The first real introduction those of us on the rendezvous had to wolves was from a retired biologist who had studied wolves during the first years of their return to Idaho. His area of expertise was the interaction between wolves and other carnivores, such as cougars – something that Oregon’s Department of Fish and Wildlife is currently investigating itself.

|

| Can you identify the skulls? (Danica Swenson) |

In addition to learning about differences in behavior, seeing and handling preserved skulls from wolves, cougars, and coyotes illustrated just how different wolves are from their fellow predators.

fter learning a bit of biology, we spent the next morning speaking with Russ Morgan, ODFW Wolf Coordinator, about how the state is dealing with wolves in Oregon. Morgan is a source of information for the political forces controlling wolf recovery – like the legislature and the agency for which he works.He also has extensive hands-on experience (quite literally) with wolves including collaring them so that their movements can be monitored. In fact, Morgan has collared OR-4, leader of the Imnaha pack, no less than four times. OR-4, has been the target of possible lethal control measures on several occasions. In one instance, with just minutes to spare, he was saved by a legal injunction that temporarily halted the state-sanctioned killing of wolves. He is now entering what is considered old age for a wolf in the wild and has fathered many of the pups born in Oregon.

|

| OR-4, after an encounter with an ODFW biologist (ODFW) |

Passing around a wolf-sized radio collar, we learned that not all of Oregon’s wolves are success stories. OR-18, who originally wore the collar we examined, was illegally killed in Montana back in the summer of 2014. The two-year-old male travelled to the Big Sky state, where wolves can be hunted legally with the proper licenses, after failing an attempt to cross Interstate 84.

|

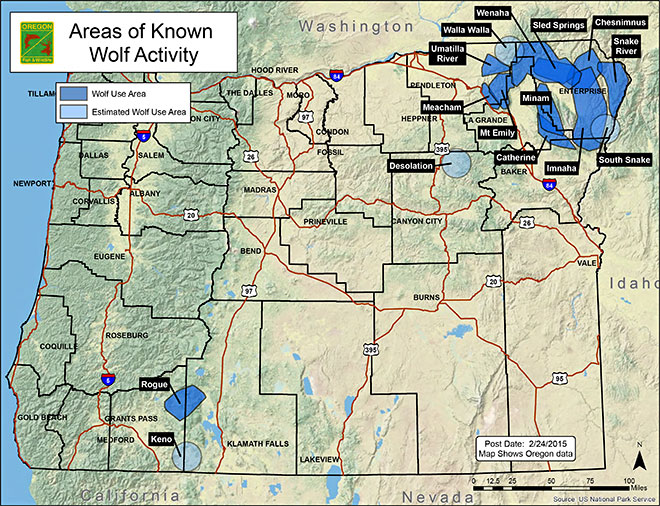

| Most of Oregon’s wolves are found in the northeast corner of the state, due in part to the barrier posed by Interstate 84. (ODFW) |

Morgan also demonstrated how the traps used to immobilize wolves about to be collared work, and gave us an overview of how he and his fellow wildlife biologists go about investigating potential livestock depredations for evidence of wolf involvement.

Having sat still long enough, members of the Wolf Rendezvous were then treated to a short hike trough some of the terrain where the Imnaha pack makes its home. With a home range that has at times neared 1,000 square miles, our expectations had been appropriately calibrated. Expecting to see the occasional wolf scat and perhaps a paw print or two, we were awestruck when, not fifteen minutes after starting our trek, our hike leaders abruptly stopped the group and demanded silence.

Cutting through the mountain air was the not-so-distant howl of a wolf pack, howling together for all the forest to hear. Those of us who had never heard the sound of a wild wolf were no more amazed than the Wallowa locals, who were fortunate enough to have already experienced a lingering call from the Imnahas.

Although the brightest highlight of the weekend had come and gone for many, our rendezvous was far from over.

The following day, we took a daytrip to the Zumwalt Prairie, where former US Forest Service biologist Ralph Anderson taught us about some of the plants that Native Americans historically foraged from the prairie. We were even treated to a taste of foraged roots, whose abundance has sadly diminished on the almost exclusively privately owned Zumwalt.

|

| Retired biologist Ralph Anderson shared his knowledge of the Zumwalt Prairie with the group. (Quinn Read) |

Thousands of elk graze on the open prairie, but our time there was during the hot hours of the day, when the herd beds down under the shade of the surrounding forests. Only livestock, mule deer, and the occasional coyote walked the Zumwalt, although the birders of the group excitedly watched as red-tailed hawks, ferruginous hawks, and one or two eagles flew overhead.

Despite its ecological importance, private owners today use the prairie more or less as a gigantic grazing plot for livestock, mostly cattle. However, the Nature Conservancy has purchased a small portion of the Zumwalt, intent on bringing conservation-minded stewardship to the high grassland.

After absorbing all we could from our short time with Anderson, we headed to the home of a local rancher, who has unfortunately lost cattle to ODFW-confirmed wolf depredation, although he believes the true number of losses attributable to wolves is actually higher than the official count.

Sitting in his well-manicured lawn and listening to his concerns, we obtained a glimpse into the complex reality of those opposed to wolf recovery. This rancher wasn’t a heartless monster, intent on killing everything with claws. He understood that wolves were here to stay, but was frustrated that unlike cougars and coyotes, he couldn’t “take care” of problem predators near his cattle if they happened to be wolves. Like some other Oregon ranchers, the man we spoke to is trying to prevent friction with wolves using non-lethal deterrents, some of which are provided by the state.

|

| Imnaha pup (ODFW) |

Putting a human face on the other side of Oregon’s wolf controversy did make many of the rendezvous participants question the way we had been thinking about the issue. However, it is important to remember that ranchers and those in the livestock industry have powerful lobbying groups, such as the Oregon Cattleman’s Association, Farm Bureau, and national organizations like Americans For Prosperity relaying their concerns to Oregon’s legislators and other decision makers. Wolves, on the other hand, don’t have direct access to the statehouse in Salem. They require concerned Oregonians who value native wildlife to take initiative and speak on their behalf.

All in all, the sixth annual Oregon Wild Wolf Rendezvous was a roaring success, but it highlighted the need for those of us who want to see wolves return to their native range in Oregon to listen and learn, but also to speak up. If we do, many more Oregonians, from Wallowa to Waldport and everywhere in between, may someday hear a far-off wolf pack raise their voices in thanks.

In addition to learning about differences in behavior, seeing and handling preserved skulls from wolves, cougars, and coyotes illustrated just how different wolves are from their fellow predators.

'

'