By Eleanor Solomon

Imagine yourself in your house. Now, imagine that you can never leave your house or you will risk getting run over by a car, or getting shot. Out your window you can see all your neighbor’s houses, and you want to talk to your neighbors, but they can’t leave their houses either. You and everyone else in the neighborhood are stuck in your houses, for the rest of your lives, until perhaps someone brave enough leaves her house and risks her life to reach other people. Pretty horrible, right? This is the situation many wild animals are in today.

Of course, wild animals do not have homes or neighborhoods. But they do have something called a home range. A home range is the place animals normally inhabit to find food and mates. Animals need their home range to live safely and healthfully. Roosevelt Elk, a type of elk that lives in the Cascades, have a home range of about three to six square miles. Fishers, which are a member of the weasel family, have a home range of about ten square miles. Wolves have an astonishing home range of 200 to 500 square miles.

In urban areas, parks and pieces of green are typically isolated from each other. Wild animals that might be in these natural areas have no way of reaching other animals and other food. They are all trapped in their tiny pieces of land. This is called habitat fragmentation.

There are two main types of habitat fragmentation: natural fragmentation and human fragmentation. Natural fragmentation is caused by natural events such as rivers changing course, wildfires, flooding, or avalanches. When natural fragmentation occurs, the organisms in the ecosystem are usually able to adapt to the fragmentation because they have evolved to be able to survive natural disturbances. Natural fragmentation is also usually temporary because plants will recolonize a disturbed area, making it easier for other species to return.

Human fragmentation, on the other hand, is more permanent. Human fragmentation is caused by man-made developments such as roads, croplands, residential development, and commercial development. When houses are built, it is impossible for plants to recolonize and for other animals to return.

A simple solution to the problem of human habitat fragmentation is to improve animals’ access to wildlife corridors.

|

|

|

A wildlife corridor is a path that animals and plants use to travel between habitats. These connections help wild animals find mates and maintain genetic diversity within a species. When genetic diversity is low, a species is vulnerable to disease and is less able to adapt to its environment. Connections between habitats are essential for the health of species within habitats.

But wildlife corridors are often obstructed by barriers, usually roads. When animals can’t get through a wildlife corridor, they can’t reach other habitats to find mates, and their genetic diversity plummets. In order to prevent this, a wildlife crossing provides a path through the barrier and lets animals cross safely through the corridor. These crossings can take the form of crossings under or over a highway, waterways and streams, urban greenways, and vegetated pathways.

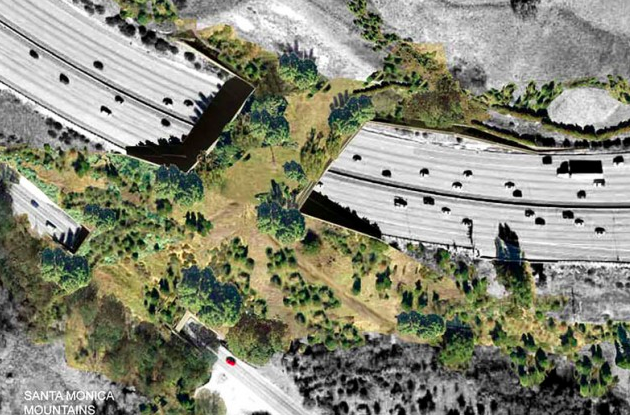

Wildlife crossings could help several species survive in the US. For instance, in Southern California, cougars are extremely scarce. The Santa Monica Mountains, west of Los Angeles, are believed to contain a total of six cougars, and of these only two are males. US 101, an eight-to-ten-lane highway, makes up the northern boundary of the Santa Monica Mountains. Only two cougars have successfully crossed the 101 highway and made it in or out of the Santa Monica Mountains. Six cougars is not enough to make a healthy population, and many Californians believe the cougar population will die out as a result. State officials are planning a wildlife crossing to help the cougars cross the highway. The crossing would be the first in California, shown above. The cougars may yet have a chance if this crossing is built.

|

|

|

Some wildlife corridors connect entire regions. A wildlife corridor in North America connects the Yukon Territory in Canada to Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. Yellowstone is renowned for its diverse and abundant wildlife, but the animals in it were isolated and unable to mix with other animals outside of the park. In 1993, in order to maintain these animals’ genetic diversity, people began to carve out a path for a wildlife corridor between Yellowstone and the Yukon Territory in Canada. The corridor spans a migration route that animals have followed for more than 6,000 years. Additionally, the Yukon Territory has abundant wildlife, including grizzly bears, that if connected to Yellowstone could improve Yellowstone’s biodiversity greatly.

Since the corridor was improved, the target species of the corridor, grizzly bears, have traveled through the corridor toward each other from each region, and they are the closest they have been to one another in 100 years. In the picture below, region 8 contains a healthy population of grizzly bears that have steadily been moving downwards into Montana, and towards the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which is region 11. The Yellowstone to Yukon project aims to finally connect the divided grizzly bears in coming years.

In 2012, the only wildlife crossing in Oregon was built. It crosses under Highway 97, near Bend, and its target species is the mule deer, a type of deer whose habitat and population had been decreasing. Mule deer in the Cascades spend the summer in the high Cascades, and then migrate east, across Highway 97. The busy highway, however, blocked their way, and when they attempted to cross they were often killed. Since it was built, a variety of species including deer, bears, elk, cougars, and moose have crossed under the Oregon bridge an estimated 150,000 times. Also, the addition of a wildlife crossing underneath the highway has helped to greatly reduce the number of traffic fatalities.

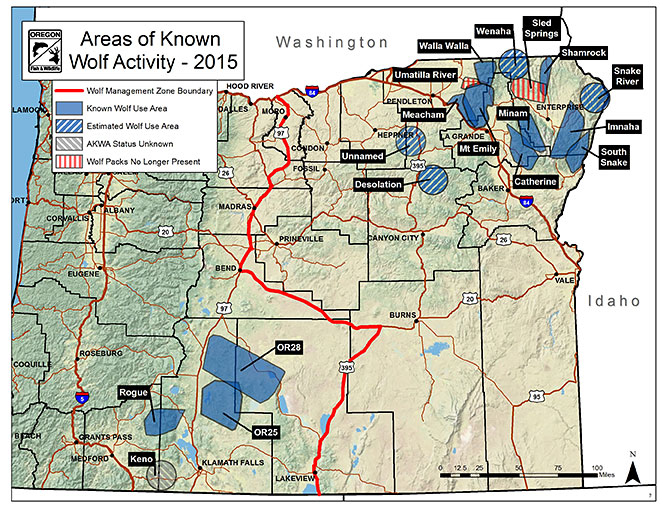

There is a great need for more wildlife crossings in Oregon. The wolf population in Oregon, currently at less than 80 known adult wolves, is located primarily in the northeastern corner of the state in and around the Wallowa Mountains. Interstate 84 cuts across the corner of the state where the wolves are located, and many believe the reason for the wolves’ restricted habitation in Oregon is because of Interstate 84. The highway is difficult and dangerous to cross, and as a result makes it difficult for wolves to reach the rest of the state. Wolves are an essential part of a healthy ecosystem. Recall that wolves have a home range of 200 to 500 miles. In order to expand the population of wolves in Oregon, constructing several wildlife crossings over I-84 seems critical.