TAKE ACTION TO PROTECT OREGON'S IMPERILED SPECIES

What is the Oregon Conservation Strategy?

The Oregon Conservation Strategy was created by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) to outline a set of priorities and recommendations for addressing Oregon’s fish, wildlife and habitat conservation needs.

The Conservation Strategy - Oregon’s Wildlife Action Plan - aims to maintain healthy fish and wildlife populations by protecting and restoring habitats, and preventing extinction of imperiled species. Wildlife Action Plans are Congressionally required blueprints for conserving the nation’s fish and wildlife, and are designed to help states implement proactive measures to prevent species from becoming endangered. Despite the critical importance of the Oregon Conservation Strategy, since its inception, it has lacked sufficient funds to fully implement necessary actions. For example, though 88% of all fish and wildlife in the state are not hunted or fished (many of which are included in the Oregon Conservation Strategy), they only receive about 4% of ODFW’s budget. That’s why Oregon Wild is working to address this issue by advocating for the passage of the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act. Learn more about what that means for Oregon’s fish and wildlife.

What are Strategy Species?

Strategy Species in the Oregon Conservation Strategy are Oregon’s species of greatest conservation need. There are 294 Strategy Species including 17 amphibians, 58 birds, 29 mammals, 5 reptiles, 60 fish, 62 invertebrates, and 63 plants and algae.

These species are experiencing population decline, habitat loss, and other issues that put them at risk. The Oregon Conservation Strategy compiles information on the needs of each species to make addressing these issues easier. The list of Strategy Species was put together with the input of regional biologists and species experts. Strategy Species are designated by ecoregion so that focused conservation efforts can be made where they are most necessary and impactful.

This approach also takes into account specific sites where large concentrations of animals gather. These Conservation Opportunity Areas are important places where animals gather together for migration, breeding, and sheltering. For example, Klamath Lake hosts the largest concentration of wintering bald eagles in the continental United States! And the largest known Vaux’s swift roost in the world is in an old school building in Portland! These large groups of animals are especially vulnerable to habitat alteration and disturbance because they heavily rely on a specific location.

Diving into Oregon's Ecoregions

Oregon is divided into nine ecoregions. Each ecoregion is designated based on climate and vegetation. By focusing on ecoregions, each area’s specific conservation and management needs can be defined. Below is an overview for each ecoregion, with an example of a species found there.

CLICK THE ECOREGION

NEARSHORE | COAST RANGE | WILLAMETTE VALLEY | KLAMATH MOUNTAINS | WEST CASCADES | EAST CASCADES | COLUMBIA PLATEAU | BLUE MOUNTAINS | NORTHERN BASIN & RANGE

Oregon’s Nearshore ecoregion runs along the coast and extends 3 nautical miles into the ocean. This ecoregion also includes portions of estuaries where species depend on saltwater that comes in from the ocean. The Nearshore ecoregion supports a diverse array of fish, invertebrates, marine mammals, birds, algae, plants, and micro-organisms in its variety of habitats such as rocky reefs and intertidal mudflats.

Commercial fishing and shipping are large parts of this ecoregion’s economy in addition to ample recreation opportunities like boating, surfing, and wildlife viewing. The human activities in the Nearshore ecoregion provide many services for Oregon’s population, but can also have negative impacts on coastal ecosystems.

The Oregon Nearshore Strategy addresses the needs of marine species, including saltwater fish, shellfish, marine mammals, seabirds, and their habitats, including kelp forests. Oregon’s nearshore environment is managed by the state and mainly falls under the purview of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW).

|

Ochre sea stars play a very important role in the rocky intertidal zone. In fact, research done on the ochre sea star is what resulted in the concept of a keystone species – a type of species that plays a defining role in its biological community. In the case of ochre sea stars, their predation upon mussels allows for much greater biodiversity in the rocky intertidal environment. Without sea stars present to hunt, mussels will take over and monopolize the rocky intertidal zone, leaving little room for the many other diverse and colorful residents of the tide pool community! Learn more about the species here! Art by Rebecca Marx. |

The Coast Range includes Oregon’s entire coastline and stretches eastward to the borders of the Willamette Valley and Klamath Mountains ecoregions. This lush region contains picturesque forests, rivers, coastal wetlands, impressive dune systems, beaches, and tidepools.

The Coast Range has the wettest and mildest climate in the state thanks to cool, moist air from the ocean. Most of the ecoregion is dominated by temperate coniferous rainforests. The Coast Range is also home to the highest density of streams found in Oregon.

If you’ve ever experienced the beauty of the Oregon coast, it will come as no surprise that more and more people continue to flock there for summer vacations and even permanent relocation. As demand for waterfront property and recreation opportunities increases, some areas of the coastline are developing rapidly. Unfortunately, development is often concentrated in sensitive areas near rivers and estuaries. This type of residential development causes loss of habitat that is important for wildlife.

Forestry is the primary industry in the inland portion of the region, while commercial fishing, tourism, and recreation are the prevalent industries along the coast. Inland, the timber industry continues to have many impacts on habitat within the Coast Range ecoregion. There are guidelines, like those in the Northwest Forest Plan, however these do not protect mature and old-growth forests, roadless areas, municipal watersheds, and complex young forests that are recovering from fire. Watershed functions and habitat complexity in stream and riparian areas are in need of restoration after years of intensive forestry practices.

In 2022 Oregon Wild represented the concerns of the conservation community and negotiated with private forestry corporations to overhaul private forest practices. Thus the Private Forest Accord was born, and its implementation will be a key step towards protecting important habitat, including waterways on private lands.

However, much of the Coast Range ecoregion is publicly owned, which gives the state more power to carry out management and conservation plans. Efficient planning, land use regulations, and habitat restoration are major concerns for this ecoregion. Special attention needs to be given to conserving and restoring sensitive habitat such as streams and estuaries.

|

Pacific lampreys are found in the Coast range ecoregion (also in Columbia Plateau, East Cascades, Klamath Mountains, West Cascades, Willamette Valley, and Nearshore) and begin life in gravel-bottomed streams. They spend 3 to 7 years floating downstream and acting as filter feeders, cleaning up the mud and sand as they go. Once the lampreys enter the ocean, they mature into adults. As adults, lamprey function as parasites feeding on fish and marine mammals. They spend their adult lives in the ocean before returning to freshwater streams to spawn. Pacific lamprey may not be the most colorful fish in the sea, but they are valued members of aquatic ecosystems. They are indicators of a healthy stream ecosystem and are an important first food for Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest! Learn more about the species here. |

The Willamette Valley is nestled between the Coast Range and the Cascade Range. This valley is home to gentle landscapes shaped by historic flooding that deposited many layers of sediment to create rich soil. This fertile soil along with abundant rainfall makes the Willamette Valley the most well known agricultural region in Oregon.

The Willamette Valley ecoregion is also the most urban one in the state, containing 9 of the 10 largest cities in Oregon and is the fastest-growing ecoregion. The population is projected to nearly double within the next 30 years. The rapid urbanization of this area continues to cause increased pollution and habitat loss.

Prior to European colonization, the Kalapuya People utilized a regime of regular fires (cultural burns) to help maintain the valley’s mosaic of grasslands, oak savannas, wet prairies, and other open habitats. Since 1850, the Willamette Valley ecoregion has been greatly altered by development and much of the historical habitat has been fragmented. Over 95% of land in the Willamette Valley is privately owned, making large-scale conservation projects difficult to carry out.

In order to help the natural ecosystems of the Willamette Valley ecoregion thrive, we need to focus on the needs of individual at-risk species and the protection of key sites, as well as promoting the creation and protection of parks and natural areas, wildlife corridors, and green infrastructure within urban areas.

|

Great spangled fritillaries have bright orange to brownish wings with black spots and bands. Their range spans southern Canada and across the northern and central United States. They are currently listed as a conservation strategy species in the Willamette Valley and West Cascades. Female great spangled fritillaries lay their eggs near violets in late summer and the larvae exclusively feed on the leaves of violets (mostly on Viola glabella in western Oregon). Adults feed on the nectar of many flower species including milkweeds, violets, vetch, and red clover. Learn more about the species here! |

The Klamath Mountains ecoregion encompasses a mountainous region of southwestern Oregon. Interstate 5 runs right through the middle of this area, which includes the cities of Roseburg, Grants Pass, and Ashland. The ecoregion is home to several popular and scenic rivers, including the Umpqua, Rogue, Illinois, and Applegate rivers. These rivers provide important habitat for salmon and steelhead. Oregon Wild is currently working to protect more Wild & Scenic Rivers in Oregon, many important wildlife hotspots. This ecoregion’s climate is rainy in the western portions, warm and dry in the interior valleys, and snowy in the mountains.

Partly due to the wide array of climate and terrain, the Klamath Mountains ecoregion is host to world-renowned levels of biodiversity. This region was included in the World Wildlife Fund’s assessment of the 200 locations most important for species diversity world-wide and has been proposed as a World Heritage Site and UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. The Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument was established in 2000, protecting 86,774 acres of grassland and forest in order to preserve biodiversity in this region. Additionally, the Soda Mountain Wilderness was designated in 2009, and encompasses 24,700 acres.

While there are many protected areas in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion, residential communities continue to grow rapidly, especially in the Medford and Roseburg areas. This ecoregion is the second fastest-growing in Oregon. Urbanization is leading to habitat loss in these valley communities.

Historically, the forests of this ecoregion were filled with fire-adapted vegetation and experienced smaller fires more often as a part of a healthy cycle. However, years of management techniques focused on fire suppression have led to decreased forest health and increased intensity of wildfires as a result.

In order to assist this ecoregion’s precious plant and animal communities, we need to implement careful land use policies to prevent further habitat loss.

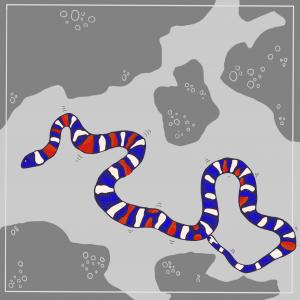

|

The California mountain kingsnake stands out with its distinctive red, black, and white bands. This medium-sized snake is sometimes mistaken for the venomous coral snake, but the California mountain kingsnake is harmless and can be distinguished by the black borders around each red band. The California mountain kingsnake lives in moist microhabitats within pine forests, oak woodlands, and in the chaparral of southwestern Oregon valleys. Besides the Klamath Mountains ecoregion, it is also found in the Coast Range, Columbia Plateau, East Cascades, and West Cascades. This elusive snake spends most of its time underground, concealed in rock crevices, rotting logs, or shrubs in open wooded areas near streams. Their main prey include lizards, birds, small mammals, and other snakes. As predators, snakes help to control the populations of their prey and keep their ecosystems in balance. Learn more about the species here. |

|

The West Cascades ecoregion spans the entire length of Oregon following the western slopes of the Cascade Mountains and reaching into the foothills of the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue Valleys. Much of this region’s topography has been shaped by its volcanic past. The volcanic crests of the West Cascades ecoregion include Oregon’s highest peaks: Mt. Hood, Mt. Jefferson, and the Three Sisters.

This ecoregion is made up almost entirely of coniferous forests. The climate is generally wet with winter precipitation falling as rain at lower elevations and snow in the mountains.

The West Cascades ecoregion is sparsely populated, containing just over 1 percent of Oregon’s population. Some local economies are shifting from timber dependence to a focus on recreation and tourism. However, logging still remains a threat to the area. This ecoregion’s picturesque forests and mountains provide ample opportunities for hiking, camping, birding, and other outdoor recreation.

By many metrics, the West Cascades ecoregion is considered the healthiest in the state. Much of the remaining old growth forests on public land are managed with an emphasis on biodiversity under the Northwest Forest Plan. This plan is intended to address the needs of more than 1,000 species of plants, animals, and fungi. While the Northwest Forest Plan provides positive conservation guidelines, there are still many limitations. Forests in the West Cascades ecoregion are facing increasing risk of severe wildfire. Reintroduction of healthy burns and protection of important wildlife habitat features are key for these ecosystems.

|

Great gray owls have striking, bright yellow eyes, and circular facial discs with concentric rings of dark and light feathers. Their bodies are mottled gray, brown, and white. The great gray owl is Oregon’s tallest owl, measuring up to 32 inches in length! Great gray owls have a broad range in the northern hemisphere spanning the northern regions of Europe, Asia, and North America. These owls are a rare sight in Oregon, where they can only be found in forested areas above 3,000 feet in the Cascades, Blue, and Wallowa mountains. Great gray owls require old-growth forests for nesting, and need open grassing clearings for foraging. These owls are predators, feeding on small mammals such as gophers, mice, shrews, squirrels, and weasels. Learn more about the species here. |

The East Cascades ecoregion cuts a vertical slice through the center of Oregon. This area reaches from north to south along the eastern side of the Cascade Mountains. The climate varies dramatically from cool and moist at its western border, to much drier at its eastern edge. The volcanic history of this ecoregion is evidenced by its numerous dramatic features including buttes, lava flows, and craters. The East Cascades ecoregion is home to one of the most well-known craters in Oregon, Crater Lake, which was created by the explosion of historical Mt. Mazama 7,700 years ago.

The East Cascades supports a remarkable level of biodiversity. Its many lakes, reservoirs, and marshes provide exceptional habitat for waterfowl, amphibians, fish, aquatic plants, and aquatic invertebrates.

Tourism and recreation, forestry, and agriculture encompass the majority of this region’s economy. Timber industry practices and unsustainable fire suppression have altered the stands of ponderosa pine. The forests are now young, dense mixed-species stands that are at increased risk of intense forest fires and disease. Rapidly expanding residential development is increasingly causing habitat loss in the East Cascades. Wildlife are losing important riparian zones and wetlands, and are facing decreased mobility due to busy highways cutting through their ranges, highlighting the need for wildlife bridges and corridors. In order to conserve the natural wonders of this ecoregion, careful limits on development must be enacted, along with better forest management to protect forests, wildlife refuges, and natural habitats.

|

Greater sandhill cranes need large emergent marsh-meadow wetlands with both wet and dry areas for nesting and foraging. These cranes breed throughout southeast, south central, northeast and central Oregon and are found in the East Cascades, Northern Basin and Range, and West Cascades ecoregions. The largest breeding concentrations occur at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge, and nature preserves such as Sycan Marsh. Over 240 pairs of Greater sandhill cranes have established nesting territories at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, and one banded crane was recorded returning to Malheur for 27 years! There is also an increasing winter population of Greater sandhill cranes on Sauvie Island, much to the delight of Portland-area bird watchers. Learn more about the species here. |

|

The Columbia Plateau stretches across the top of Oregon from the eastern slopes of the Cascade Mountains to the Blue Mountains ecoregion. This region is greatly influenced by the powerful hydrology of the Columbia River, which delineates its northern border. Ancient cataclysmic flooding events have shaped this ecoregion’s floodplains and deposited silt and sand across the landscape. The Columbia Plateau is known for an arid climate with cool winters and hot summers.

The Columbia Plateau’s agriculture conditions are utilized to produce the vast majority of Oregon’s grain. This region also produces staples such as potatoes, onions, and fruit.

Agriculture creates a high demand for water, and has led to decreasing groundwater levels. Intensive agricultural practices are also leading to soil erosion in the region. Outreach, education and incentive programs should be implemented to encourage landowners to implement better management techniques such as no-till farming, and careful water usage.

Almost all of the land within the Columbia Plateau ecoregion is privately owned, leading to high levels of habitat fragmentation. This makes conservation efforts harder, as there is limited connectivity among patches of high quality habitat. The areas that are available for native plant and wildlife conservation are often small fragments, such as roadsides and sloughs. Private land ownership and current land use regulations present an obstacle for large-scale ecosystem restoration.

However, there is hope for conservation in this region. Efforts will need to focus on restoring and maintaining natural ecosystem functions within privately owned landscapes. Focusing on agriculture techniques that have conservation principles in mind and restoration of riparian areas will greatly benefit this ecoregion’s native flora and fauna.

|

Townsend’s big-eared bats are medium-sized bats with pale gray or brown fur and buff colored undersides. As the name indicates, these bats have very large ears reaching up to 38 mm in length. When laid back, these long ears extend to the middle of the bat’s body! They are found in many ecoregions including the Columbia Plateau, Blue Mountains, Coast Range, East Cascades, Klamath Mountains, Northern Basin and Range, West Cascades, and Willamette Valley. Unlike many bats that tuck themselves into cracks and crevices, Townsend’s big-eared bats prefer open roosting areas. They use caves, mines, insulated buildings, and occasionally, hollow trees. Learn more about the species here. |

Oregon’s largest ecoregion, the Blue Mountains ecoregion contains a diverse mix of deep rock-walled canyons, glacially-cut gorges, sagebrush steppe, juniper woodlands, mountain lakes, forests, and meadows within its boundaries. This ecoregion encompasses a wide swath of northeastern and central Oregon, even extending into Washington and Idaho.

Named for its largest mountain range, the Blue Mountains ecoregion is characterized by short, dry summers and long, cold winters. Much of the precipitation in this region falls as snow, due to the high elevation.

This ecoregion is home to Hell’s Canyon National Recreation Area and Hell’s Canyon Wilderness, which Oregon Wild worked to protect with the Hells Canyon Wilderness / National Recreation Area Act of 1975. Working to preserve these areas was one of Oregon Wild’s first projects!

This ecoregion’s broad river valleys contain cattle ranches as well as wheat and alfalfa production. The Blue Mountains ecoregion has some of the largest intact native grasslands in the state, but unsustainable grazing practices are taking a toll on native habitat. Riparian areas, wetlands, and shrublands have been converted to agricultural uses leading to highly fragmented habitat. Wildlife need connectivity and corridors in order to survive in the lower elevation valleys of this region.

Wood products are also a large part of the economy of the Blue Mountains ecoregion. Forest habitats have been impacted by unsustainable fire suppressions and logging, leading to increased vulnerability of forests to insects, disease, and climate change impacts like uncharacteristically severe wildfire.

This ecoregion is popular for big game hunting and tourism. Increased recreational pressure, along with habitat loss and degradation due to industry, have increased invasive species and vulnerability to wildfire, and put native wildlife at risk in the Blue Mountains.

|

Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, the largest wild sheep in North America are one of two subspecies of wild sheep native to our beautiful state of Oregon. They can be found in habitats with large expanses of open grassland, canyons, rocky outcrops and cliffs. Unfortunately, populations of Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep were extirpated from Oregon in the 1800s due to unregulated hunting, habitat loss and destruction, and diseases contracted from domestic animals. However, there is hope for the species’ recovery! Current populations exist in Oregon thanks to reintroduction efforts led by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife that started in the early 1950s. There are now about 800 Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep in northeast Oregon, focused around the soaring Wallowa Mountains and the steep canyons of the Snake river. Learn more about the species here. |

The Northern Basin and Range ecoregion is situated in the southeastern corner of Oregon. Sagebrush communities dominate the numerous flat basin landscapes separated by isolated mountain ranges. This is Oregon’s driest ecoregion, with characteristically low precipitation and even desert-like conditions in the farthest southeastern corner of the state.

The Northern Basin and Range ecoregion has a history of ranching and farming. Livestock and agriculture are major parts of the economy. Past decades of overgrazing by livestock caused serious long-term ecological damage throughout the ecoregion. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 put some protections in place and rangeland conditions have improved throughout the ecoregion. However, some areas are slow to recover and still in need of restoration efforts.

Historical overgrazing and fire suppression led to the invasion of non-native grasses, which have greatly altered many sagebrush steppe habitats in the Northern Basin and Range ecoregion. Invasive plant species have replaced native plant mosaics in many areas. Greater sage-grouse are charismatic inhabitants of this ecoregion and excellent indicators of sagebrush habitat quality. Efforts must be made to improve conditions for native species, restore sagebrush steppe habitat, address invasive species, water quality, and recover from overgrazing.

|

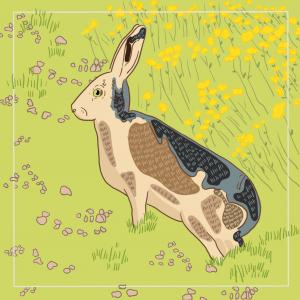

The white-tailed jackrabbit has an expansive range in North America, spanning across southern Canada and the northern United States from the west coast to the Great Lakes. These jackrabbits live in open grasslands and sagebrush plains, and are sometimes found in coniferous forests and subalpine meadows. They are particularly associated with bunchgrass grasslands. As herbivores, white-tailed jackrabbits help to maintain a healthy ecosystem by preventing the overgrowth of vegetation. They are also important sources of prey for predators such as foxes, coyotes, bobcats, cougars, snakes, owls, eagles, and many species of hawks. Learn more about the species here. |