An Untold Story, the Promise of Wilderness, and the River Democracy Act

By: Marina Richie

“We’ve learned that safeguarding a river requires that people become engaged in the future.”

Tim Palmer, Wild and Scenic Rivers, An American Legacy

Read other posts in this series:

Beloved Metolius River

Every Wild Place Has a Story

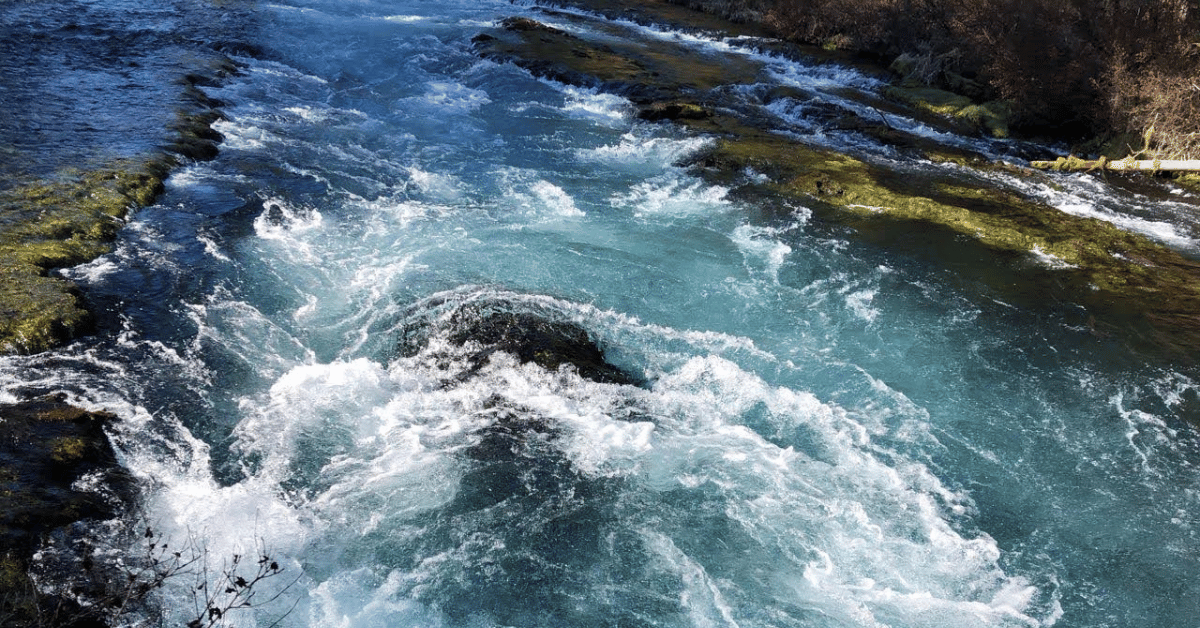

Sunlight strikes a chord across the Metolius. An American dipper, perched on a fallen tree in the water, sings a melody of whistles, riffs, and churrs. The river gives the beat and the hum on a late winter’s day. The great forests seem to rise even higher as if lifted from their roots by the wild aria. I stand still at the Allen Springs Campground, transfixed by a small gray bird dipping and dipping.

On that mostly cloudy day, the river flowed like polished obsidian. Under blue skies, the swift currents can dazzle in turquoise, jade, and whitewater. Deep clear pools. Icy cold. Refuge for the wily native bull trout. Legendary for flyfishing. Haven for centuries-old ponderosa pine, incense cedar, Douglas-fir, grand fir, and western larch.

One of the largest spring-fed rivers in the United States, the Metolius flows 29 miles north to Lake Billy Chinook. At the Head of the Metolius viewing area, you can see the birth of the river. Emergence. Frigid waters bubble up through mossy rocks whispering of origin 1.4 million years ago. Then, Black Butte erupted to blockade the ancestral headwaters of the Metolius in today’s Mount Washington Wilderness. Yet the river found her way, seeping into porous fractures in the lava rocks. Fed by Cascade snows and rains, two springs converge to enter the light-filled world at rates that range from 67 to 130 cubic feet per second. The river soon strengthens from more springs originating in the Mount Jefferson Wilderness.

The melody that is the Metolius rushes into our hearts as if to whisper—protect…protect…precious freshwater. Fortunately, people who love this river and the interwoven great forests continue to heed the message. The legacy extends back in time, including a 1931 designation of a Forest Service Research Natural Area for ancient ponderosa pines near the river–the first in the Pacific Northwest.

The Omnibus Oregon Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1988 Act added the Metolius River as part of legislation that still holds the record for adding the most river miles of any state at one time—54 rivers and four tributaries. To be part of the system assures the rivers will remain free-flowing and never dammed. Much later in 2009, the Metolius Basin earned special status as Oregon’s first and only “Area of State Critical Concern,” putting an end to plans for destinations resorts that would have tapped into groundwater and impacted the headwater springs.

The Metolius we know today would be very different if people had not turned their passion to activism. Like the critical feeder streams entering the river from headwater springs in the Mt. Jefferson Wilderness, acts of heroism merge in the free flow to be forgotten, unless we pluck the stories from the main channel. Tell the tales in the way of oral traditions passed down over generations. Tales that are best repeated and expanded upon around a campfire.

Part of environmental storytelling is to draw attention to what we have saved as reminders never to take the status quo for granted—like the treasured national forest campgrounds of the Metolius River. For those who have come to know them well, the names evoke a halcyon day: Riverside, Camp Sherman, Allingham, Smiling River, Pine Rest, Gorge, Lower Canyon Creek, Allen Springs, Pioneer Ford, Lower Bridge, and Candle Creek.

An Untold Story: Paving Paradise?

However, there was a time in the late 1980s when the Deschutes National Forest planned to pave the roads, install flush toilets, and build huge pads for RVs. To do so, they would have cut down many of the centurion trees. Gorge Campground with the most glorious ponderosas of all would have been unrecognizable. The industrialization didn’t stop there—with schemes for a paved bike trail right on the riverbanks and fish cleaning stations (despite the fact the Metolius is catch-and-release only). This is an untold story.

Bob Warren and Mary Maggs Warren enjoy the Metilous River

Enter Bob Warren, longtime environmentalist and early days’ Oregon Wild board member. He and his wife Mary Maggs Warren love the Metolius. Every year, they head east from their home in Eugene over Santiam Pass to camp there for a week or longer. They’ve come to know individual sites for their immense ponderosas, cedars, and firs, each with the lull of the Metolius close by.

At the time of the despicable plan, Warren served as the natural resource policy advisor to Congressman Peter DeFazio. When he got wind of the scheme from Penny Allen of Friends of the Metolius, he went straight to DeFazio who was shocked. He, too, knew the campgrounds as sacrosanct. It didn’t matter that the river was outside his district. He gave his approval for Warren to do whatever he could to stop the proposal steaming along with little public knowledge. Despite the risk to his career from powerful business interests pushing for development, Warren never hesitated.

“My philosophy has always been simple,” he said. “If you find yourself in the right place to do the right thing at the right time, then do it.”

To win for the Metolius, he relied on locals with intimate knowledge like Allen who ran the House of the Metolius, a private nature resort. He strategized over beers at the Deschutes Brewery with Tim Lillebo, then the eastern Oregon field representative for Oregon Wild.

For Warren, protecting the Metolius from irreversible harm was intensely personal. He even wrote a letter to Forest Supervisor Norman Arseneault in the imagined voice of his then 16-month-old son.

“This appears to be nothing less than the planned destruction of a place my Dad loves, a place I hope to visit when I’m older.” The words I find most prescient from the copy of the typed letter he shared with me are these: “Quality is what will be rare in my lifetime. Theme parks will be easy to find.”

Towering ponderosa pines reach far above the tree canopy into a blue sky

Warren wasn’t about to let down his son. On behalf of DeFazio, he arranged a Metolius field trip for the Oregon congressional staff. Both the staff of Republican Senators Bob Packwood and Mark Hatfield were there. The magic of the Metolius has a reputation for erasing most partisan divides. Missing from the field trip was the aide for Republican Representative Bob Smith, despite the Metolius falling in his district. After that two-day outing (involving the Forest Service and separately a trip led by Penny Allen), Warren said the sentiment was unanimous. All wanted the riverside campgrounds to stay as simple and humble as possible with all the big trees standing and protected.

Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., DeFazio applied his influence on the Forest Service Chief, then Dale Robertson, serving under President George H.W. Bush. Next came a forceful letter from DeFazio and signed by the Oregon delegation (absent Representative Smith) directing Robertson to drop the “recreation” plan for the Metolius. Done. Game over.

The Deschutes National Forest withdrew the plan. Warren learned from the Forest’s public affairs officer that many fellow employees applauded DeFazio’s letter. They, too, shared a reverence for the Metolius. Today, the simple campgrounds continue to merge with nature. The noble trees stand. Riverside—once slated for the biggest development of all—is a walk-in, tent only campground.

“Peter DeFazio really did “save” the Metolius from the Forest Service,” Warren said. “It was my deal, and I put it together, but only on his authority. The management plan would have destroyed the character of the place while putting in motion an unstoppable transition to tourist development. Visiting the area today I marvel at how much it has not changed from that first time I visited in 1985.”

Every advocacy story has a lesson. We must always be vigilant. Cultivate sources who know a place intimately. Sometimes we need to go right to the top. All federal agencies depend on the public to call them to task when needed. In fact, they rely on us. When it comes to politicians and their staff, take them to the field—away from offices and cell phones. And most of all? Apply the power of love, as Warren did with the letter from his son.

What’s Next? River Democracy Act

The quest to fully protect the Metolius is far from over. The splendor of the Metolius River cannot continue without caring for the entire watershed. Designating the mainstem of the Metolius as a national wild and scenic river system was a first step. While immensely important for preventing dams and other safeguards along a half-mile corridor, allowed activities vary depending on whether termed wild, scenic, or recreational. “Wild” is strictest and “recreational” the least limiting. The first 11.5 miles of the Metolius are “recreational” and the next 17.1 are “scenic.” While the Forest Service interpreted the Act to allow for the outlandish campground scheme, Warren said the designation gave them leverage to stop it.

Today, Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley’s River Democracy Act would add more than 3,215 miles to Oregon’s 2,100 miles of designated rivers (now comprising just two percent of the state’s river miles). Many streams are included, a recognition that all rivers depend on their tributaries. Oregon Wild is working hard to return rivers and streams removed from an earlier version of the bill– honoring the work of thousands of Oregonians who nominated favorites.

Fortunately, the current version does include four Metolius tributaries: Jack, Canyon, Candle, and Brush Creek. A protective half-mile buffer would offer wildlife safe passage through intact forests between the Mt Jefferson Wilderness and the river. Where the creeks enter the river, wildlife gathers. At one confluence, I witnessed a belted kingfisher, river otters, and a bald eagle within five minutes.

A Metolius Wilderness

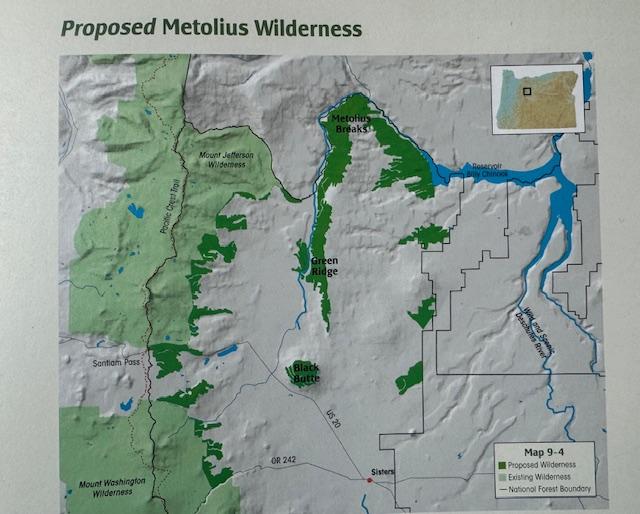

There’s another grand opportunity waiting in the wings—a Metolius Wilderness that Andy Kerr (another early Oregon Wild staffer and renowned environmentalist) proposed in his 2004 book, Oregon Wild, Endangered Forest Wilderness.

In this 60th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, it’s time to brush off that fine book filled with excellent maps and details for new wilderness. So far, the roadless areas included in the Metolius proposal are intact, according to Oregon Wild’s Erik Fernandez, based in Bend. The 39,411 acres (62 square miles) feature Black Butte, additions to the Mt Jefferson Wilderness, the Metolius Breaks, and Green Ridge.

Map from Oregon Wild, Endangered Forest Wilderness, by Andy Kerr

Green Ridge Logging Threat

Always there’s the dance of defending the status quo to keep designated wilderness possible. Enter the Green Ridge Project, a 25,000-acre sprawling logging plan of the Deschutes National Forest within habitat for the northern spotted owl, protected under the Endangered Species Act. As part of so-called restoration thinning, the project targets enormous grand firs and Douglas-firs that are critical for the owl. The logging boundaries are adjacent to part of the proposed wilderness and some dip into de facto roadless areas.

A cedar along the Metolius River steams in the early morning sun

Thanks to the vigilance of Oregon Wild, Central Oregon Land Watch, Blue Mountains Biodiversity Project, and others, the Forest Service might be scaling back. But it’s not enough when 5000 acres appear to be slated for commercial logging of trees greater than 21 inches in diameter. Logging would take place in riparian areas. New roads would fragment habitat.

While the trees still stand, it’s never too late to save them.

Returning to the riverside of the singing dipper on the next morning, the sky is clear. I pause by a cedar and ponderosa fused at their bases and living this way for centuries. Nearby, a lofty ponderosa pine forks forty feet up and then splits into six vertical trunks. The day is warming. Mist rises from the Metolius. Trees wet from melting snow are misting, too. Breathing. Exhaling. A dipper lilts into a jazz riff.

Marina Richie is the author of Halcyon Journey, In Search of the Belted Kingfisher, winner of the 2024 John Burroughs Medal for distinguished natural history writing. She lives in Bend and serves on the board of the Greater Hells Canyon Council. www.marinarichie.com