Hordes of people were out and about along the Deschutes River, enjoying a warm, sunny day in Bend, Oregon. Some were on bikes, others were with their dogs. And others–well, at first, you might not know what they were doing.

They were wearing hard hats and carrying long wooden beams and posts. Most looked to be struggling under the weight and awkwardness of their loads, audibly sighing in relief once they could drop them at their intended destination right next to the riverbank. Others in the group configured these posts and beams into a fence along the river’s edge. Enthusiastic smiles and high-fives were passed around, and then a few of them started up the hill again to retrieve more beams and posts.

In case you were one of the confused onlookers that day walking by this odd sight, this was, in fact, a group of Avid Cider, Oregon Wild, and U.S. Forest Service staff working to build fencing to protect sensitive riparian vegetation and streambanks along a popular section of the Wild & Scenic Deschutes River.

Northwest Is Our Core: Cider for a Cause

This Fall, Avid Cider partnered with Oregon Wild and Conservation Northwest to launch the Northwest Is Our Core program, an initiative to raise awareness and funds for wildlife and forest conservation across the Pacific Northwest. A portion of cider sales and 100% of profits from some very cool merch were donated to these conservation causes.

Avid Cider has been a proud partner of the Oregon Brewshed Alliance© since the Spring of 2024 and we were honored when they reached out to Oregon Wild asking us to be their conservation partner for the first year of this campaign.

Cider and conservation? We’ll drink to that!

Putting in the (restoration) work on the Upper Deschutes

To celebrate the end of the Northwest Is Our Core program, Avid, Oregon Wild, and local staff from the Deschutes National Forest teamed up to continue building fencing along the Deschutes. This restoration work, focused on a designated Wild & Scenic section of the Deschutes near Rimrock Trailhead (aka GoodDog), has been ongoing for several years in an attempt to protect sensitive vegetation in the riparian area. Due to the high popularity and traffic at this area, the trails and streambanks have become significantly eroded in recent years. Fencing helps direct people (and dogs) to designated trails and river access points, reducing the amount of erosion from off-trail use.

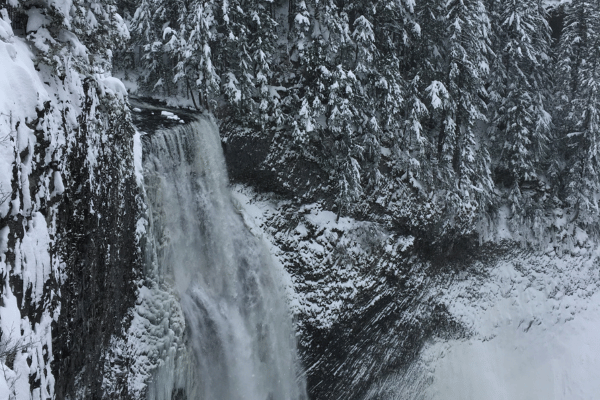

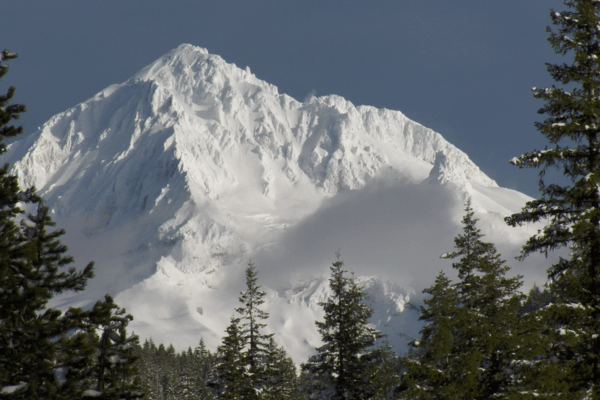

The Upper Deschutes River was designated Wild & Scenic in 1988 for its incredible ecological, scenic, and recreational values. Hundreds of miles of trails run along the river and within its adjacent forests, visitors from all over flock to the Deschutes for its world-renowned whitewater and fly fishing opportunities, and locals enjoy the vast physical and mental health benefits of a stroll or picnic along a wild river. The river corridor also provides important habitat for mule deer and elk, eagles and osprey, native trout, threatened species like Oregon spotted frogs, and a whole host of other wildlife.

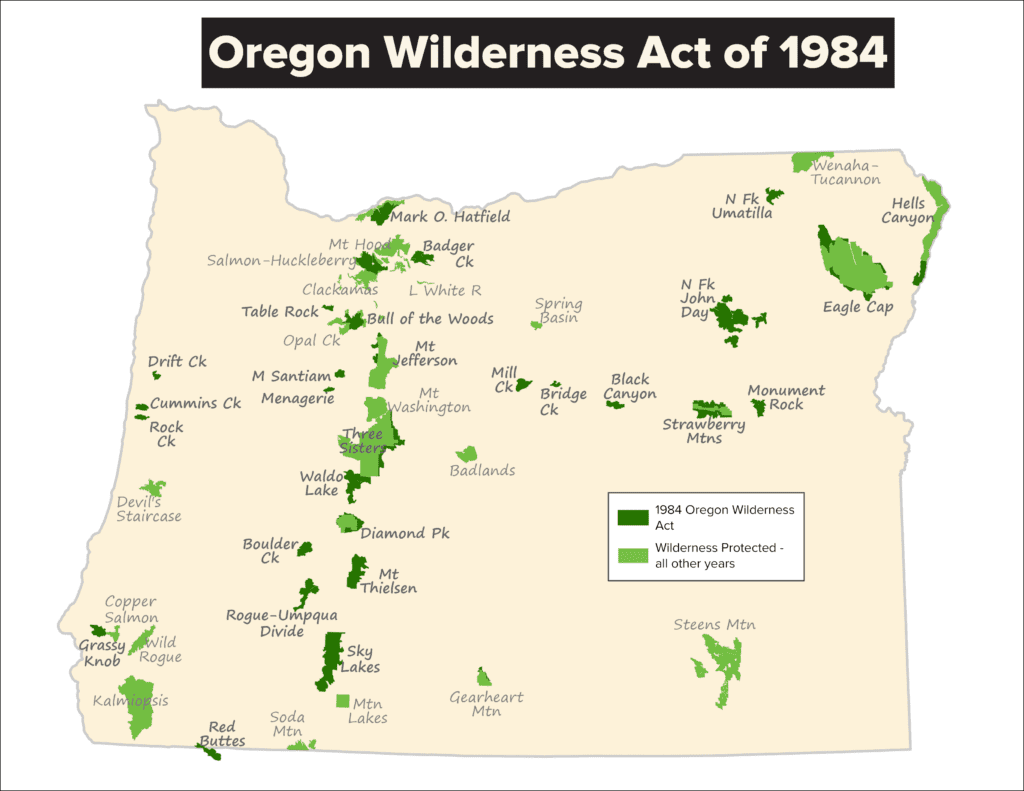

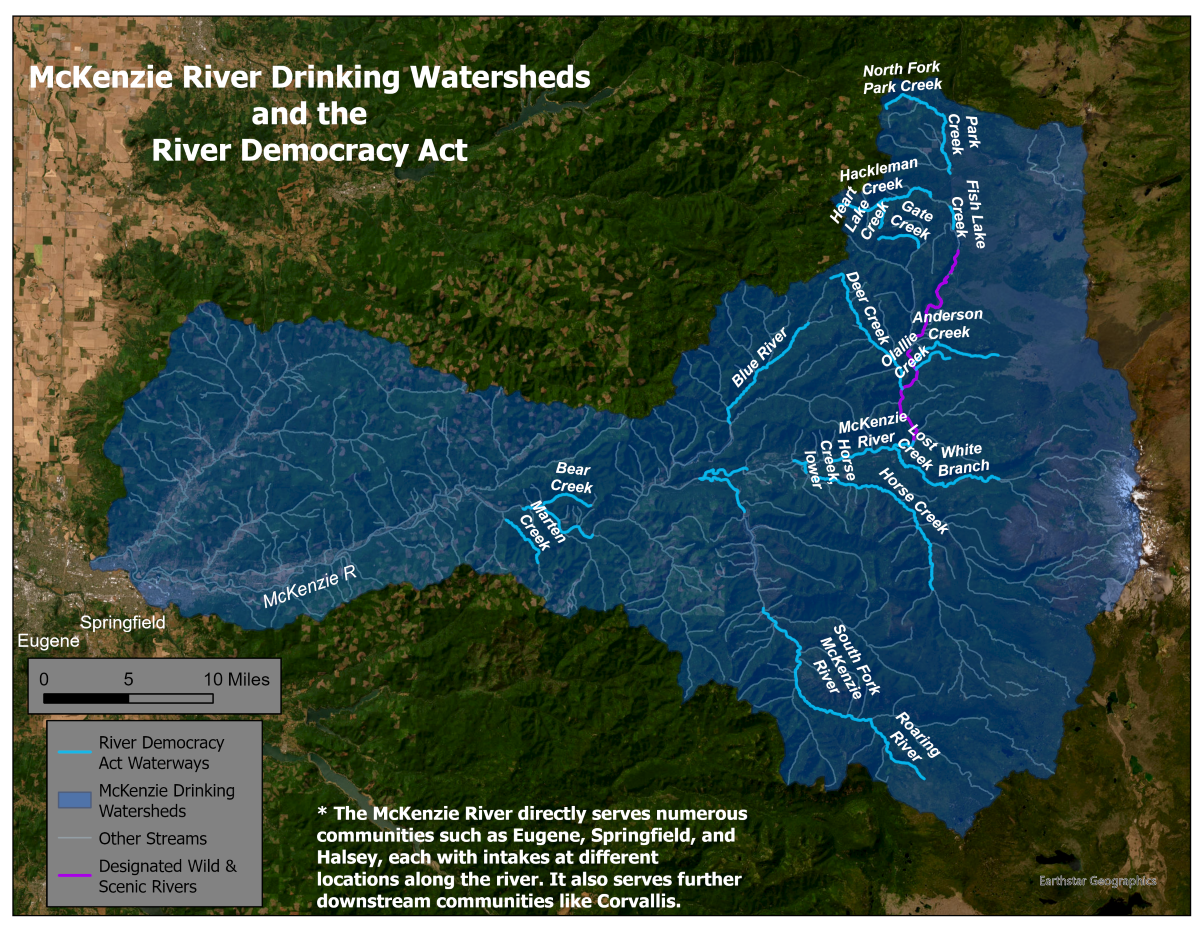

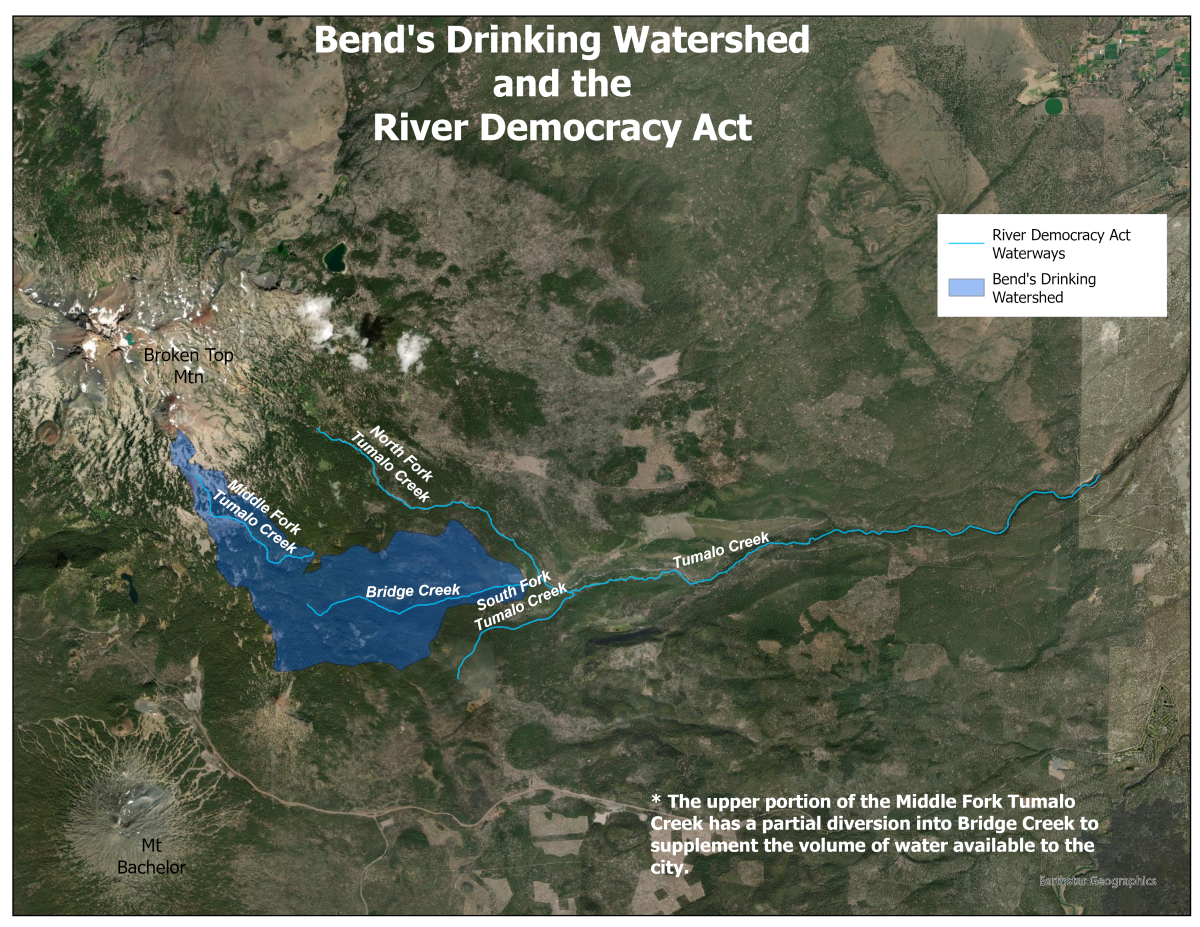

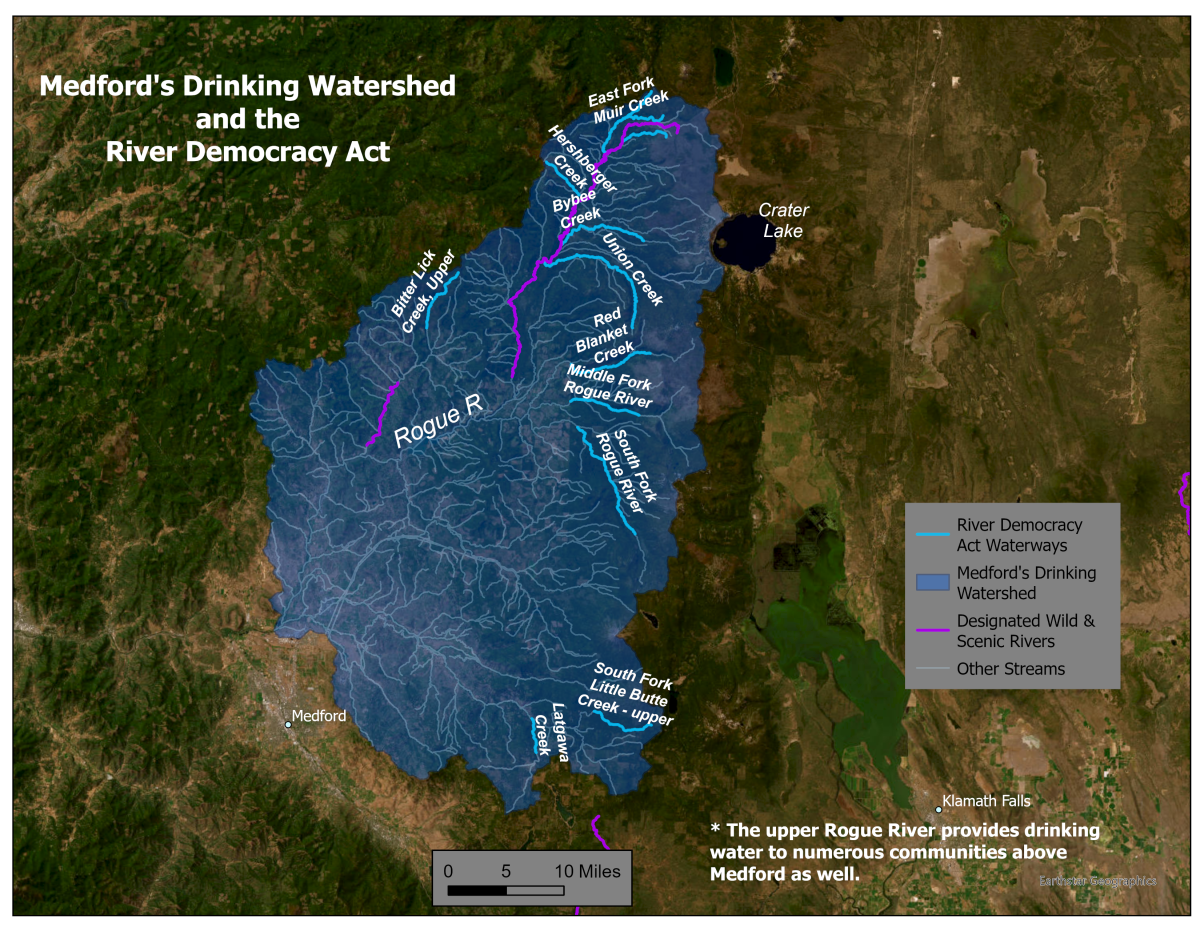

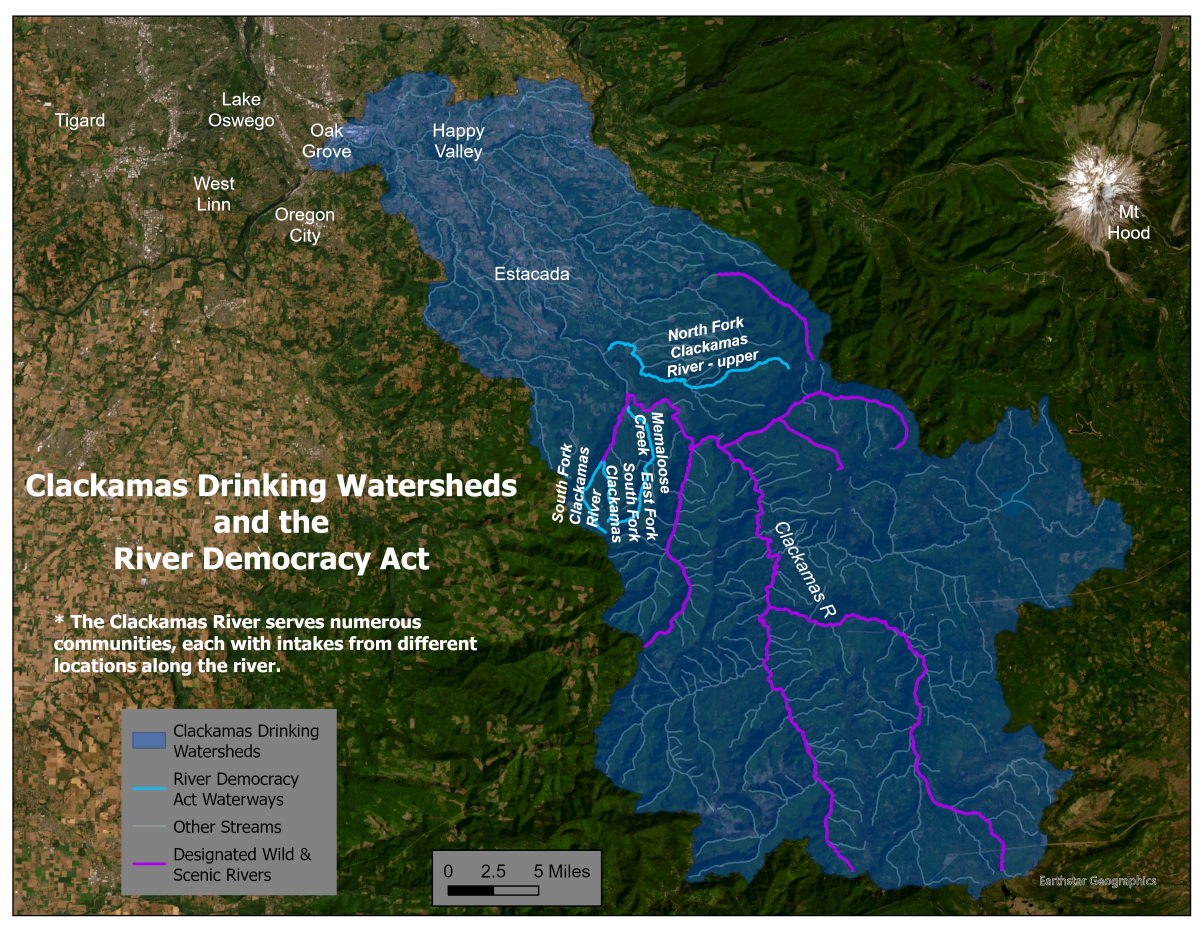

Unfortunately, climate change, drought, development, and poor upstream and downstream water use activities have threatened this special river and those (human and non-human) who rely on it. Trail work and restoration work like the Avid/Oregon Wild/USFS crew did that day helps. Oregon Wild is also working to pass Senator Wyden’s River Democracy Act, which would protect over 3200 miles of stream all across the state, including many within the Upper Deschutes watershed. By protecting these critical headwater streams of the Deschutes, we help protect clean water and wildlife habitat downstream.

Thanks to businesses like Avid Cider and everyday Oregonians who care about this special river, we can safeguard the Deschutes and the important values it provides. Become a Citizen Co-sponsor of the River Democracy Act today and tell your members of Congress to pass this historic bill.

For a wilder Deschutes.