On February 3rd, 2021, Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley introduced the Oregon River Democracy Act of 2021 to better protect clean drinking water sources, recreational opportunities, and wildlife habitat. This historic bill proposes expanding Oregon’s network of Wild & Scenic Rivers by over 4,700 miles and would protect segments of numerous key rivers across the state, from the desert streams of Owyhee country to the roaring rivers of the Coast Range.

Update December 2022: Senator Wyden announced a new version of the River Democracy Act. This new version includes 3,215 miles of Wild & Scenic River protections, a substantial reduction but still very much in the range of an historic scale. There are some waterways that Oregon Wild is working to have added to the bill to ensure the most important are included.

Here you can learn more about some of the incredible rivers in this proposal – why they’re important and worth protecting.

Oregon Cascades

Some of Oregon’s most iconic rivers flow out of the Cascades and into the Willamette River – from the Clackamas and Santiam, to the McKenzie and Middle Fork Willamette. Some of these rivers have stretches designated as Wild & Scenic, while their headwater streams and major tributaries are not. These streams flow from glaciers and high elevation springs and out of protected wilderness – providing cold, clean water essential for native salmon and trout and connecting ancient forests and wildlife habitat from the Willamette Valley to tree line.

Western Cascade river systems provide drinking water and nearby recreation for a majority of the state’s population. The ancient forests that shelter their headwater springs and streams provide amazing, and free, water filtration. The colder, cleaner, and more protected these streams are, the better water quality comes into drinking water intakes further downstream for Eugene, Salem, Oregon City, and many other communities. As the climate warms and changes, these headwater streams will become even more important for providing a steady source to downstream communities.

Likewise, streams in the Clackamas, Santiam, McKenzie, and Middle Fork Willamette watersheds connect Oregon’s population centers to world-class recreation on accessible public lands. From whitewater rafting on the McKenzie River, to scenic drives along the South Santiam or Quartzville Creek, to spending a day picnicking at Memaloose Lake, viewing Oregon’s 3rd tallest waterfall on Salt Creek – the scenic highways and trails that lead Oregonians into the forests and mountains follow truly wild and scenic rivers.

Featured Rivers/Watersheds:

- South Fork McKenzie River

- Middle Fork Willamette River

- South Santiam River

- Breitenbush River (and its North and South Forks)

- Oak Grove Fork of the Clackamas River

Central Oregon

Central Oregon’s volcanic legacy makes its rivers and streams incredibly unique. Some literally spring forth from the ground at the base of mountains, as if by magic. Others have no visible outlet stream, instead they sink slowly into an underground network of old lava flows before joining with a major river downstream. Their backdrops can’t be overlooked – these waters flow in the shadow of enormous dormant (and active!) volcanoes, through towering forests and overflowing wildflower meadows, and into the deep river canyons that define the landscape.

Middle Schoolers Nominate Tumalo Creek

Middle school students in Bend, Oregon chose to nominate beloved local waterway Tumalo Creek after spending time there as a class: “We believe that Tumalo Creek should be designated as a Wild and Scenic River to protect it for years to come because it represents everything that we love in Bend — the beautiful outdoors, being with friends/family, and having fun! The students of Pacific Crest Middle school feel the need to protect the creek because it is part of our community”.

Photo by Peter C. Blanchard

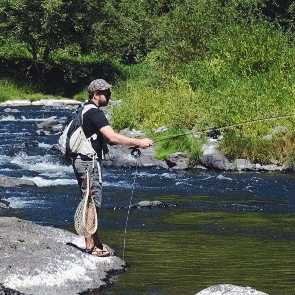

The region is made up of three main river systems – the Deschutes, Crooked, and Metolius – but in the high desert water is precious, so the creeks and streams that feed them are equally important. Smaller waterways like Tumalo Creek and Deep Creek provide critical water sources for wildlife (and people!), and act as fish “nurseries” for bigger rivers in the region, while larger rivers serve as important recreational hubs for anglers and whitewater boaters. Having access to so many beautiful public waterways is a boon, and towns like Bend and Sisters have seen decades of substantial economic benefit from the money that this tourism brings in. Studies by Headwaters Economics have found that Deschutes County (and other “recreation counties” like it) has been more resilient during economic downturns specifically because of our access to public lands & waters.

Featured Rivers/Watersheds:

- Tumalo Creek

- Fall River

- Paulina Creek

- South Fork Crooked River

- Deep Creek

Coast Range

From meandering streams that flow through remnants of quiet, out-of-the-way old-growth forests, to short but incredibly scenic creeks sheltered by Sitka spruce trees that draw thousands of visitors each year, to strongholds for native fish like tributaries to the Nestucca River, the rivers proposed for protection in this region offer important scenic, recreational, fisheries, wildlife, and ecological values. The region includes scenic byways along the South Fork Alsea River, complete with waterfalls, and one of the best known ancient forest groves in the state – Valley of the Giants on the North Fork Siletz. In addition, streams unique in all of Oregon flow through the Oregon Dunes ecosystem, where shifting sand and water support rare species and incredible recreation.

Few streams in Oregon’s Coast Range remain unimpacted by heavy management of forests in the region, which makes protected stretches – whether in the headwaters or an estuary – vital for connecting habitat for rare and threatened species like Coho salmon, marbled murrelets, northern spotted owls, and coastal martens. Amid a fragmented sea of clearcuts and roads, native species need these stream corridors to thrive, and residents and visitors seek out these islands of beauty and help local economies thrive. Coastal rivers and streams that are still shaped by natural processes are vital for these connections and experiences – from the Drift Creek watershed, to the headwaters of the Yachats River, to streams flowing from Mount Hebo into the Wild & Scenic Nestucca.

Featured Rivers/Watersheds:

- South Fork Alsea River

- Drift Creek

- Gwynn Creek

- Nestucca River headwaters

- Tenmile Creek

Southwest Oregon

The “Wild Rivers Coast” and Rogue River watershed are home to some of Oregon’s most iconic rivers. The Siskiyou region is one of the few sizable intact landscapes along the entire pacific coast between the Olympics and the San Francisco Bay area. This region also missed the last ice age, resulting in the most unique ecosystem in Oregon, home to plants found nowhere else on the planet. Oregon’s only redwood forests call this corner of the state home, so while you may not see bigfoot here you might find Ewoks.

Recreation Economy Pays Dividends

Many counties across Oregon benefit from recreation dollars, and data shows that it helps them in more ways than one. Communities that integrate recreation into their economy benefit from higher average incomes, fasten earnings growth, a reliable stream of new residents, and more stability during economic downturns.

The world class rafting, hiking and fishing along the Rogue River is the heart of southwest Oregon and it’s most iconic river. The Rogue, it’s tributaries, and other rivers are home to an array of fish species ranging from the prehistoric looking sturgeon to salmon, steelhead, and lamprey. The rivers also provide clean drinking water to a number of communities in the region.

Featured Rivers/Watersheds:

- Rough & Ready Creek

- Forks of the Rogue River

- Illinois River

- Smith River

- Applegate River

- Winchuck River (redwood forests)

Umpqua Basin

Starting with the South Umpqua headwaters in the Rogue-Umpqua Divide Wilderness, past the confluence with the incomparable North Umpqua River, and flowing free all the way to the ocean, the Umpqua is the second longest undammed river in Oregon. The scenic Umpqua system provides absolutely essential salmon and steelhead habitat, high quality water, and offers some of the best recreational opportunities in the state – from hiking to fishing to scenic drives. Tributaries of the North Umpqua River that comes out of the Cascades, and the Smith River that cuts through the Coast Range to the Umpqua both contribute outstanding river values to the region.

Salmon and steelhead are the lifeblood of the Umpqua… and vice versa. The vast undammed network of streams in this watershed are vital to Chinook and Coho salmon and wild steelhead, and indigenous people have depended on these fisheries for millenia. In fact, Steamboat and Canton Creeks, flowing into the North Umpqua Wild & Scenic River, are recognized as being the best steelhead streams in the Umpqua Basin and part of these watersheds are within the Frank & Jeanne Moore Wild Steelhead Special Management Area.

Featured Rivers/Watersheds

- Upper North Umpqua River

- Steamboat Creek

- Fish Creek

- North Fork Smith River

- Smith River

Northeast Oregon

Northeast Oregon is a landscape of superlatives. Rivers flow from some of the states highest peaks towards North America’s deepest canyon. The region hosts the most complete assemblage of native wildlife in Oregon. Moose make their homes in wet forests, wolverine prowl wilderness headwaters, and wolves began their recovery after wetting their paws in the Snake River. Tantalizing reports of grizzly bears, lynx, and fisher persist. Endangered fish make their home in cold clean waters.

Wild and Scenic Wildlife Corridors

Habitat loss and fragmentation are major concerns for those who care about wildlife. This is one of the reasons wildlife corridors and the habitat connectivity they provide have emerged as important solutions. The habitats around rivers can be integral in helping wildlife travel or move to higher altitudes. As the climate changes and Oregon warms, this connectivity to cooler habitats will be all the more important. In addition, these river-miles are also generally more intact than other landscapes that have seen more logging and development.

The region connects the Rocky Mountains to the Blue Mountains, and the Cascades and Coast Range beyond. From small streams to big iconic rivers, the waterways of Northeast Oregon provide critical and irreplaceable habitat corridors that flow through alpine areas, deserts, wet forests, and prairies alike

Indigenous people have made this region their home since time immemorial with the oldest evidence of human habitation in North America being recently discovered in the Snake River Watershed. Water is life, and protection for these waterways and surrounding landscapes will provide wildlife habitat, clean cold water, recreation, and opportunities for solitude and wildness that make the region so unique and alive.

Featured Watersheds:

- Grande Ronde River

- Snake River

- Umatilla River

- John Day River

- Powder & Burnt Rivers

High Desert

While the world-class rivers of Oregon’s high desert are treasured for their abundant, quiet solitude, they are by no means devoid of color, life, or cultural touchstones. From the small headwater streams in the mountains to the mighty John Day and Owyhee Rivers, these waterways form the lifeblood of a vast region. Desert waterways are vital for fish and wildlife. In the Steens region, bighorn sheep and golden eagles rely on these waters, while in the John Day and Deschutes River Basins, salmon and steelhead spawn.