Walking into a grove of towering trees on the edge of Crabtree Lake, trunks all wider than I can get my arms around, feels like I’ve entered a place outside of time. Carved by glaciers, the steep walls of Crabtree Valley and the moist environment around Crabtree Lake have protected pockets of ancient trees from fire for nearly a millennium. The centuries these trees have stood here – withstanding wind and snow; seeing fellow giants fall and new life grow; standing guard over the salamanders, rotting logs, and fungal spores that all contribute to the web of biodiversity that makes up their home – are beyond what most humans can fathom.

Human timelines are often more short-sighted. For decades, the lands surrounding this oasis of old growth were heavily logged by private companies and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). In fact, the heart of the valley was once owned by a timber company and could have suffered the fate of the surrounding forests, but starting in the late 1970s forest advocates worked for years on a plan to save this special place. Eventually, a land swap resulted in the BLM acquiring the land from the timber company. The agency recognized the importance of the unique ancient forest ecosystem here and designated it first as a Research Natural Area and later as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern. Today these designations apply to 1,251 acres under the BLM’s Resource Management Plan.

But 1,251 acres isn’t much. A view from the air shows how disconnected this patch of forest is from other wildlands – surrounded as it is by roads and clearcuts.

Over the years I’ve taken dozens of people to Crabtree Valley, navigating a maze of logging roads and clearcuts (nearly getting lost the first few times) to reach the closed road, now softening back into the hillside, that serves as a trail.

Every trip has been memorable in its own way. On my first visit, in the pouring rain, I saw my first Pacific giant salamander near the edge of Crabtree Lake. One year, a family with young children joined our group, and years later returned and shared photos of the now-adults revisiting the forest. Hiking guide author William Sullivan marveled at “King Tut” and “Nefertiti” when he joined Oregon Wild staff on a hike into the valley in 2014. Most recently, I brought author-naturalist Marina Richie and old-growth expert and hike guide author John Cissel to this special place.

None of us strangers to wild, ancient forests, Marina, John, and I crawled over down logs and navigated through spiny devil’s club to reach “King Tut” – where we stood in awe gazing up at this ancient Douglas-fir tree with characteristic spiraling grooves in its bark. Estimated to be over 600 years old (and perhaps 800), I got a look at the tree’s canopy with a drone on this trip and saw a healthy intact canopy no worse for the wear from centuries of exposure. Next, we ambled to the spectacular grove of immense firs, hemlocks, and cedars that grow on the east side of the lake – each of us marveling at the plants, fungi, and lacey canopy that surrounded us.

With every group I take to Crabtree Valley, I’m reminded how the draw of ancient forests, to something bigger and older and more mysterious than ourselves, is something that unites people.

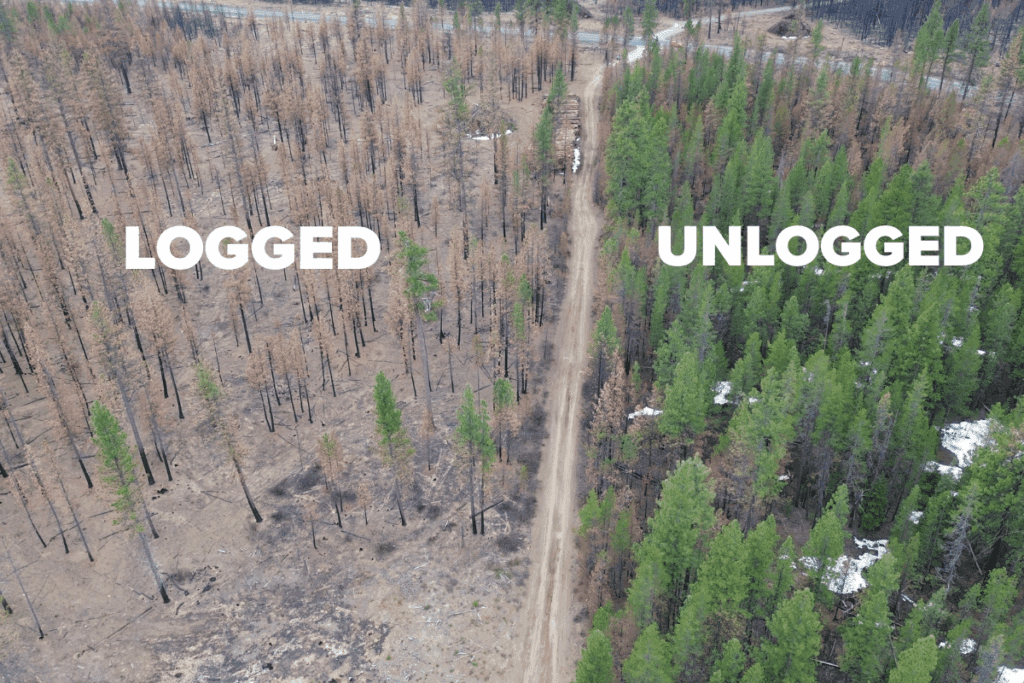

As we look to a future where climate change is putting native plants and wildlife at risk, water may be more scarce, and threats of logging in older forests are more pervasive, it will be increasingly important that we not only protect more places like Crabtree Valley, but we also must restore the interconnected forest ecosystems that once connected Crabtree Valley to the forests of the Cascades. We need to let the next ancient forests grow, whether they are recovering from fires or regrowing after past logging.

This 1,251 acres of wild forest is only still standing because of the persistent advocacy of the people who fell in love with it. Such work is difficult, especially when setbacks come as hard and fast as opportunities and successes. Here at Oregon Wild, we know protections for these special places are often hard-fought over a long period of time, but successful outcomes are well worth the effort. Whether through defending bedrock environmental laws, pushing back against plans to log mature and old-growth forests, or inspiring forest advocates through outdoor experiences, Oregon Wild is here to do this work. We do it for the love of nature; for future generations of black bears and giant salamanders, hemlocks and huckleberries; and for humans who can take respite in the deep shade of an ancient forest canopy on a hot summer day, find water running year-round from a forest-sheltered stream, and marvel at an ecosystem centuries older than they can fathom.

Support Oregon Wild’s work with a year-end donation here.

Additional resources and descriptions

Profile by Friends of the Douglas-fir National Monument

Salem Statesman-Journal story by William Sullivan

John Cissell’s description on his Old-Growth Hikes website

The hike into Crabtree Valley is featured in “Oregon’s Ancient Forests: A hiking guide” available here.