By: Marina Richie

Read other posts in this series:

Beloved Metolius River

Lookout Mountain: Roadless Beacon of the Ochocos

Hardesty Mountain Roadless Area: Vigilance, Close Calls, & Heroes

Saving the Big Trees of Badger Creek as Wilderness – A Lucky Break

North Fork Umatilla Wilderness: Saved by a Trout?

Imnaha River: Wolves, Wilderness, and Wildlands

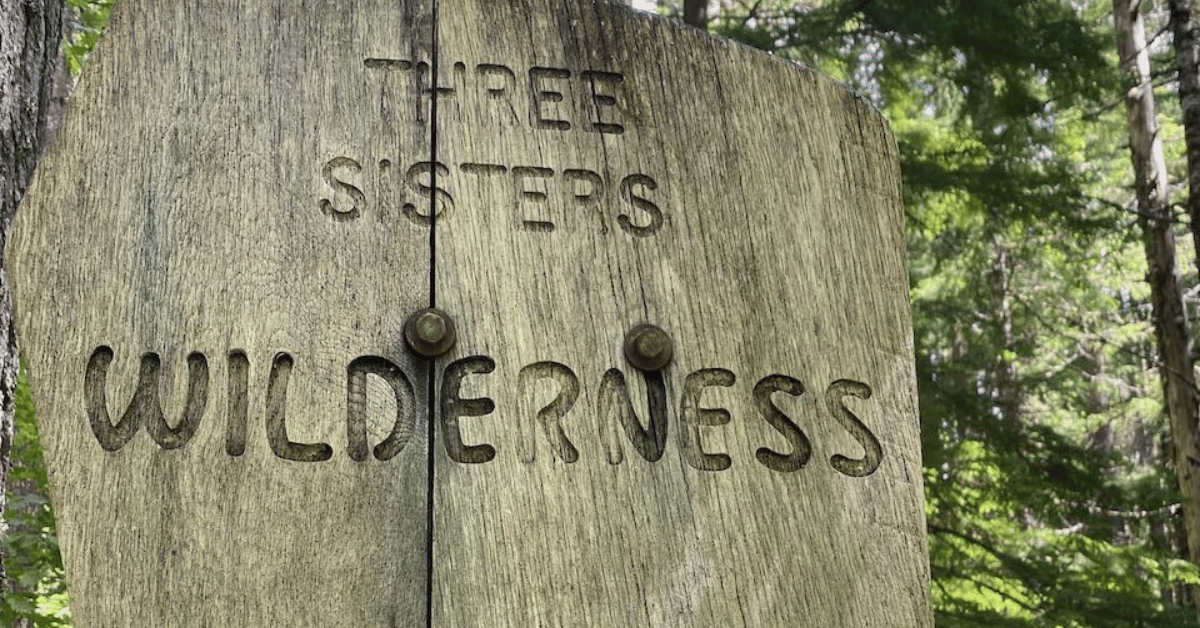

Hiking into a designated wilderness on a national forest, I often pause to admire the boundary sign. The organic shape blends like a great gray owl merging with a grand fir. Routed in the wood is the name of the wilderness and the national forest. When a sign is within easy reach, I might trace the lettering and whisper my gratitude.

Crossing the portal, my steps lighten. Here, I will not round the corner to see stumps or the gash of a new road. I will not encounter a mechanized vehicle. I will not worry about the latest timber sale to “improve” forests with chainsaws. Instead, I will open my senses to self-willed nature that is complex, entwined, and ever-changing.

What is not on the entry sign is how that wilderness came to be protected. You might call it a love story, because love is the most powerful of motivations for ordinary people to step up with extraordinary courage to advocate for wilderness with a big “W.”

Oregon has a rich and often unheralded legacy of local heroes who took great risks to keep roadless areas roadless, wild rivers free-flowing, and ancient forests safe from logging. Without their efforts, we would have far fewer wilds left today. We would also have far fewer wolves, wolverines, spotted owls, marbled murrelets, fishers, martens, salmon, steelhead, salamanders, and a myriad of life forms dependent on our last intact wildlands and rivers.

As Oregon Wild celebrates 50 years and the Wilderness Act turns 60 this year, I’m delving into a few of the stories of protection and celebrating the leadership of an organization I’ve known and supported since I was a student at University of Oregon, from 1977 to 1981. Even when living in Montana full-time from 1988 to 2015, I felt the tug of the wildlands, wild coastlines, peaks, and forests I’d come to know intimately in Oregon. In 2016—following a year as a roving naturalist—I returned first to La Grande and a year later to Bend, my home today.

I’m a nature writer, environmentalist, and author of the 2022 book, Halcyon Journey in Search of the Belted Kingfisher. I’ve served on the board of the Greater Hells Canyon Council since 2016.

Throughout 2024, look for my upcoming blogs featuring the following wildlands (listed from west to east): Hardesty Mountain, Middle Santiam Wilderness, Metolius River, Lookout Mountain, North Fork Umatilla Wilderness, and Imnaha River.

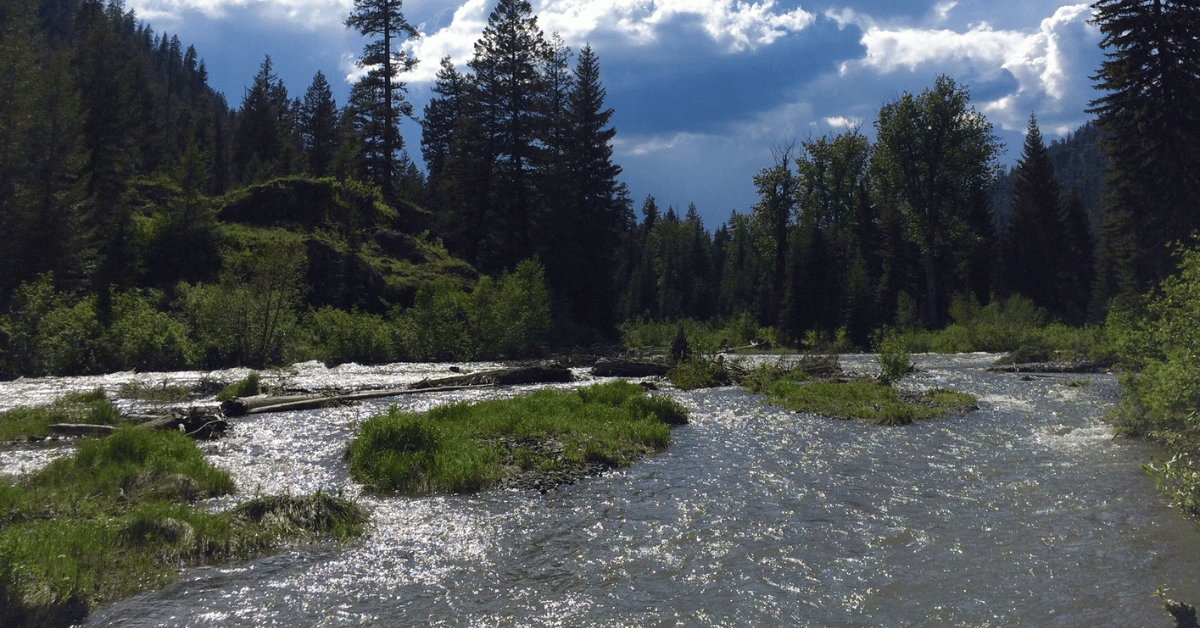

The Middle Santiam and North Fork Umatilla fall within our national system of wilderness areas. The Metolius and Imnaha Rivers are part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system. The upper Imnaha flows from headwaters within the Eagle Cap Wilderness to a confluence with the Snake River in Hells Canyon National Recreation Area. Hardesty and Lookout Mountains are roadless areas not yet protected as wilderness.

The Wild and Scenic Imnaha River

The Wild and Scenic Imnaha River

All the chosen wildlands harbor big trees and ancient forests, vital for storing carbon and biodiversity. All have critical associated wildlands in need of protection. With the exception of Middle Santiam Wilderness, the selected wilds appear within Oregon’s Ancient Forests, A Hiking Guide, by Chandra LeGue of Oregon Wild.

Writing these pieces for Oregon Wild informs a new book in progress, one that links my passion for birds with saving our threatened ancient and mature forests of the Pacific Northwest. I’ve also teamed up with watercolor artist Robin Coen to research and write prose for an exhibit called “Refugia of the Blue Mountains” (for the Wild Blues Artist in Residence of Greater Hells Canyon Council). I’m pleased that most of my writing is now interweaving like the mycelial network of roots in a wild forest.

For a sense of what to expect in the series, see the blog Drift Creek Wilderness—a Tribute (appeared in Oregon Wild’s November newsletter). I wrote of my October hike threaded with memories and the drama of a decade-long fight to save the big trees coveted by the timber industry. Designated under the Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984, Drift Creek is the largest remaining protected ancient forest in the Oregon Coast Range. On that day, I witnessed chinook salmon spawning in clear waters.

Environmentalists in 2024 are part of a long continuum of advocates who have never had it easy. Losses hit hard. Victories are sweet and often short-lived before we must roll up our sleeves again. Today, we have far more tools in our hands with social media, drones for filming from above, and even Light Detection and Ranging (Lidar), a remote sensing technology that can reveal a three-dimensional forest. No matter our advances, there’s nothing better than people out in the field as guardians, watchdogs, and for that ultimate reason—to fall deeply in love with a wild place.

Oregon Wild has grown from a scrappy grassroots group located in an old Civilian Conservation Corps building across from Hayward Field in Eugene to a vibrant organization with a staff of 20, four regional offices, dozens of volunteers, more than 4,000 members, and even more subscribers and followers.

I’m grateful for Oregon Wild’s unflagging advocacy over 50 years— protecting almost two million acres of Wilderness, and more than 2000 miles of Wild & Scenic Rivers. What’s harder to measure is what would have been logged, roaded, and degraded without vigilance, winning lawsuits, passing legislation, working hand in hand with other grassroots groups, and rallying people to take action.

The author takes a selfie in front of an old-growth tree

All our remaining wilds in Oregon form one unfinished symphony. The music grows more resonant with every roadless piece we protect, every existing wilderness we expand, every wildlife corridor we link, and every wild river and tributary added to our national wild and scenic river system.

Please contact me if you have stories to share from your experiences in the featured wildlands or know parts of the history. Thanks for coming with me on the virtual journey. Maybe I’ll see you on the trail! Look for my upcoming blog on the Metolius River next month.