When you’re out enjoying the spectacular national forests in Oregon, you’re probably not thinking about laws passed decades ago to require forest plans for these areas. But these plans, and the subsequent standards, guidelines, designations, and policies they create, make a huge difference in what you’ll experience at your favorite trail, river, or picnic spot. They certainly affect the lives of the wildlife that call these places home, the fish that swim in the streams, and the plants that thrive in the forest soil.

One of my favorite trails is tucked away in the central Coast Range, along the North Fork Smith River. The trail takes you through a steep river canyon, past enormous Douglas-fir, moss-draped bigleaf maples, and waterfalls. This area of the Siuslaw National Forest is home to threatened and rare wildlife species (from salamanders to owls), and it is designated as a Special Interest Area and Late Successional Reserve under the forest’s Management Plan and the famous Northwest Forest Plan.

The Forest Service is planning a logging project here that might be incredibly concerning if not for the constraints of these plans – namely, ensuring that management focuses exclusively on thinning young plantations for the purpose of restoring old-growth and riparian forest habitat that help threatened species.

In far Eastern Oregon, there is another forested corridor – one that connects Hells Canyon to the Eagle Cap Wilderness. This part of the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest has been identified by scientists as one of the most important and irreplaceable connectivity corridors on the continent. The landscape here is about as diverse and spectacular as it gets. When I first visited, I camped along Lick Creek. I was struck by the majesty of the mountain views, the huge scattered ponderosa pines, and dense stands of fir, larch, and spruce. I saw evidence of natural regrowth after fire. I heard my first wolf howl and saw wild salmon in the stream.

What is a forest plan?

Every national forest has a guiding management plan, as required under the National Forest Management Act. In Oregon, most of these plans were completed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when logging, roading, grazing, and mining had already fragmented most intact blocks of habitat and cut down most large and old trees over a vast landscape. These forest plans aspired to break with the destructive activities of the past and envision more “sustainable” management. Though they have often fallen short of their aspirations, these new forest plans did start to consider uses that weren’t exclusively extractive. They outlined management guidelines and direction for everything from recreation, logging, Wilderness designations, wildlife needs, and other public values – kind of like a zoning plan for a forest. Plans were intended to be revised every 15 years or when conditions significantly change. Small amendments can be made in the interim.

Today, revisions and amendments are underway to make substantial, and potentially detrimental, changes to forest plans that touch nearly every national forest in Oregon, from the iconic Northwest Forest Plan to northeast Oregon’s Blue Mountains.

The Northwest Forest Plan

In Western Oregon, initial forest management plans saw major new developments almost immediately when, after decades of habitat destruction, northern spotted owls, marbled murrelets, and salmon were listed under the Endangered Species Act. The Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP) was developed as an attempt to strike a balance between logging and protecting habitat. In 1994, the NWFP amended plans for the Siuslaw, Mount Hood, Willamette, Umpqua, Rogue River-Siskiyou, and Deschutes National Forests, as well as Bureau of Land Management lands within the range of the northern spotted owl.

However, the NWFP has always been bigger than just one species. In defining areas for protection and setting strong standards for restoration, the NWFP has led to great progress in restoring some of the damage done by decades of unsustainable logging – protecting drinking water, keeping other wildlife off the endangered species list, restoring salmon runs, stabilizing the climate, and improving quality of life which is the foundation of the growing regional economy.

Efforts to weaken the Northwest Forest Plan began as soon as it was finalized. The most consequential attack came from timber interests that opposed forest and habitat protections on Western Oregon BLM lands. They claimed logging should be the primary use of these public lands. A lawsuit settlement, initiated under the George W Bush administration, led to a revision of the BLM’s management plans in 2016. The revision essentially removed 2 million acres from the conservation framework of the NWFP, allowing more intense logging and shrinking reserves.

In 2015, the Forest Service began considering if and how to revise management plans for national forests within the NWFP area, but the revision process was shelved during the Trump administration. Now, a federal advisory committee has been convened to inform potential amendments to forest plans in Western Oregon, focusing on addressing wildfire risk, climate change, old-growth forests, tribal engagement, and rural communities and workforce.

Blue Mountains Forest Plans

Major adjustments had to be made to Eastern Oregon’s forest plans around the same time as the Northwest Forest Plan. Recognizing the need to address the rampant degradation of wildlife habitat across the region, the Eastside Screens were put in place. Among efforts to maintain wildlife habitat, the Screens protected trees 21 inches in diameter or larger. These protections have many ecological benefits, and they also helped focus the agency and communities on building common ground, rather than fighting over old-growth logging.

Covering 5.5 million acres, the three National Forests of Eastern Oregon’s Blue Mountains – the Malheur, Umatilla, and Wallowa-Whitman – have been grouped together for revision. Starting in the early 2000s, a series of failed efforts at plan revisions have provided a sneak peek of the agency’s intentions. In those previous processes, the Forest Service had an opportunity to find a balance that protected undeveloped areas, embraced new science, and brought management of these public lands in line with the modern era. Instead, their proposals adopted an outdated vision of rural economics by prioritizing extractive industries like logging and livestock, while de-emphasizing the importance of natural and cultural values like clean water, recreation, salmon, wildlife, quality of life, and carbon storage.

The Forest Service has re-initiated a new revision process for the Blue Mountains very much in character with their previous attempts. A lot is at stake in this incredibly diverse region identified by scientists as being of global importance for wildlife connectivity and carbon storage. These forests have long been subject to logging, excessive road building, overgrazing, and the exclusion of natural fires. Their recovery from past abuse, and the promise of a healthy future – for the forests, streams, wildlife, and people who depend on this landscape – hangs on a new plan’s outcome.

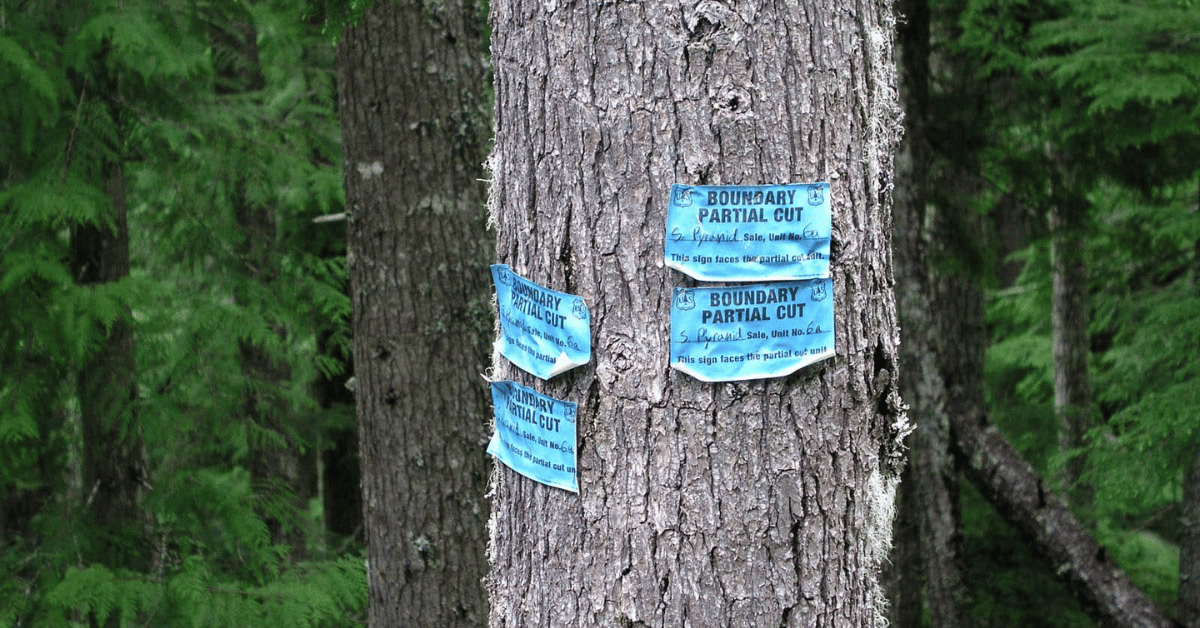

A huge project covering 87,000 acres, called Morgan Nesbit, is being planned here under the guidance of the 30-year-old Forest Management Plan. In contrast to the constraints embraced by the Siuslaw National Forest, a proposed amendment to the Wallowa-Whitman Forest Plan would allow logging of steep slopes and the largest 3% of trees that remain.

Limits and opportunities

While forest plans are incredibly consequential, they’re rarely perfect. Most are a compromise. For example, the Northwest Forest Plan, though celebrated for providing some protections for wildlife habitat and ancient forests, still allowed logging and road building in ecologically critical areas and did not fully protect mature and old-growth forests.

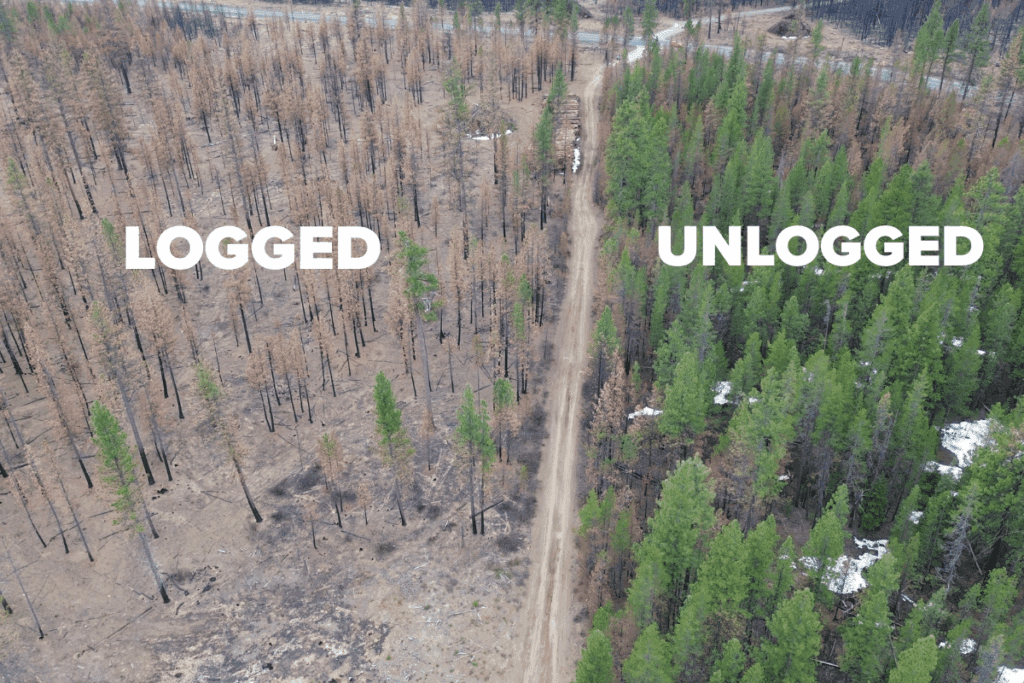

Forest plans are also subject to amendments and rule changes, directed by changing presidential administrations and agency discretion. The NWFP area saw rule changes that increased logging under the Bush administration. In Eastern Oregon, piecemeal amendments are often made to accommodate logging the largest trees under the guise of “restoration” and fuel reduction. The Trump administration tried to do away with those protections entirely.

Revisions and amendments to forest plans can be a good opportunity to reflect evolving public values and offer beneficial guidance for managing our public lands for clean water, natural ecosystems, wildlife connectivity, climate stability, fire resilience, and more. Rather than loosening standards, what we need from forest plans are more enforceable sideboards that ensure the protection of large trees and mature forests, water, and connected wildlife habitat. They should make the case for Wilderness or Wild and Scenic River protection, and set the stage for the landscape-scale preservation of natural areas and restoration of ecosystems necessary to address the dual climate and biodiversity crises and help meet national land and water conservation goals. Destructive activities like commercial logging, livestock grazing, backcountry fire suppression, and maintaining high road densities should be reduced.

With these sideboards in place, the Forest Service can focus on real restoration of watersheds that prepare for the return of salmon to their native streams, connecting habitats for species that need to migrate to adapt to climate change, and enhancing habitat degraded by mismanagement. But given the process and outcomes we’ve seen from recent revision efforts that always seem to move toward greater agency discretion and less conservation, it’s hard to feel optimistic that the Forest Service is heading in that direction.

This is why, at the same time, we need strong Administrative direction and durable protections for the landscapes, forests, and waterways that are so important for the future of biodiversity and a livable planet. To achieve this, Oregon Wild’s ongoing campaigns can complement and direct where forest plans go.

- Our Climate Forest Campaign is working to create a strong national rule to ensure forest plans protect mature and old-growth forests. Without a rule, the Forest Service has struggled to implement the vision of President Biden to protect these forests as a climate solution, and instead continues to plan and implement destructive logging projects across the country.

- With the Nez Perce Tribe and other conservation allies, we went to court and defeated an illegal effort to undermine forest plan protections for the largest 3% of trees left in Eastern Oregon. Now we’re working together to scale back piecemeal amendments to allow destructive logging proposals like Morgan Nesbit.

- We are working to pass Wilderness and Wild & Scenic River designations across the state. These are the best ways to protect Oregon’s remaining wildlands and waters for their many ecological and cultural values. Forest plans can ensure these areas are not degraded and support the case for their permanent protection until legislation is passed.

Together, we have a long history of speaking up for our vision and values. We’ll be counting on you to let the Forest Service and elected leaders know what you value about our national forests and public lands.