“Sea otters have been around for more than a million years.”

This is Bob Bailey, Board President of the Elakah Alliance, an organization working to restore sea otters to the Oregon coast.

You’ve probably seen pictures of sea otters – furry, adorable creatures that live in the ocean and hold hands. They group together in these big colonies called rafts, usually just beyond the breaking of the surf. They spend most of their lives in the ocean, only coming ashore to rest, groom, or nurse. They even give birth out at sea.

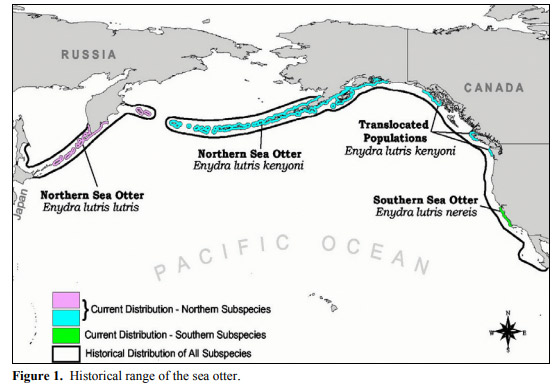

“Originally it’s estimated that between the tip of Baja California and Mexico all the way around the Pacific rim to the northern islands of Japan, there were approximately 300,000 sea otters,” says Bailey. “They’re not as big as seals, they’re not as big as seal lions. About the size of a German shepherd dog.”

“Sea otters are highly social animals.”

Danielle Moser is the Wildlife Program Coordinator at the nonprofit conservation organization Oregon Wild. She advocates for the protection and recovery of native species.

“They’re an incredibly intelligent species and are actually the only marine animal to use tools, like rocks, to break open shells,” comments Moser.

Sea otters have another special distinction. Unlike most marine mammals, like whales, dolphins, seals, they don’t have a layer of blubber to insulate them against sometimes freezing ocean water temperatures. Instead, they have extremely dense fur, denser than any other mammal.

This thick fur is one of the reasons sea otters were so valued by the native people of the Pacific Northwest, and the traders that arrived later. But some theorize that sea otters played an even more significant role in how humans first populated the coast.

As Bailey points out, “People, early people, showed up along the west coast after they came across the Bering Sea at the low stands of the sea during the last ice age. That was 15,000 years ago. And the shoreline, at least in Oregon, along the west coast, was much further to the west than it is today. So it didn’t look anything like it does today. We don’t know exactly what it looked like. But there is good speculation, hypotheses, that the kelp along the west coast, from Alaska all the way down to what we now call California and Mexico– that that kelp allowed early people to travel southward and make their way south along the coast rather than inland. Now, whether we will ever know for sure, that’s a plausible hypothesis and it was made possible because there were sea otters. Sea otters have had not only a long ecological relationship with the nearshore environment along the west coast, but they’ve had a long cultural relationship with the people that lived there.”

Similarly, in what is now Oregon, for the people of the Chinook, Coos, Coquille, and other tribes, sea otters were seen as providing ecological and economic value in addition to spiritual and cultural enrichment. In addition to their pelts being a sign of wealth and prosperity, and used in inter-tribal commerce, sea otters also played an integral role in their oral histories.

For example, the Haida– in what is now, British Columbia– have had a long history and deep relationship with sea otters. From an early age, Haida children are taught about the significant role sea otters play in their tribe and lessons on how to respect the land and only take what can be used.

Peter Hatch, is a member of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, he works on staff there and is also a Board member of the Elakha Alliance. He notes, “As indigenous people, our prosperity going all the way back is derived from the strength of our relationships to the many beings with which we share our lands and our waters. You can see that in many ways, but especially in the regalia, that people wear on ceremonial occasions be it the ventalia shells that people trade for, the woodpecker scarlett, or the yellowhammer feathers; so many things carry significance of prosperity derived from managing the environment and living in a good way.”

“Sea otter pelts were highly esteemed within our tribal communities and only certain people could afford to wear them and had the right to wear them,” says Robert Kentta. Kentta is an enrolled Siletz member and on the elected council, works in the cultural resources department for the Siletz Tribe, and is also on the Elakha Alliance Board.

In fact, when Lewis and Clark came down the Columbia River in 1806, they tried to trade for a sea otter robe.

According to Lewis’s journal, one member of the Chinook tribe was ‘draped in three elegant sea otter skins’ which Lewis and Clark very much wanted. They offered him many articles, but he would not trade one otter skin for anything other than ten fathoms of blue beads. A fathom was a strand of beads six feet in length, so the Chinook was asking for sixty feet of highly prized blue beads for one otter skin. Lewis and Clark had only six fathoms left, so they were unable to trade.

Sea otters also had tremendous spiritual value, and were used in the stories and teachings of the tribes. The sea otter symbolized a range of attributes; everything from a giver of great fortune to a never-ending curiosity and playful spirit.

Hatch shares, “Throughout our stories that tell us about how the world was put together, and inform the way that we should live today, sea otters are one of many beings we have a deep relationship with. For the Coos side of my family, I think of a specific story that illustrates the way that sea otters are really kin to us, as with many other beings. An elder from our community told a story about a young Coos woman marrying into the sea otter people, and cementing that relationship between the people and the sea otters; back at a time when animals and people weren’t as different as we see them today.”

However, the arrival of traders from Russia, Europe, and eventually, the young American republic, would drastically change life for the indigenous peoples of the Northwest and drive sea otters to the brink of extinction.