By Chandra LeGue

Waldo Lake and the forests and trails all around it is one of my “happy places.” Every summer, I love to paddle and swim in the clear, deep blue water and pick huckleberries for camp breakfast. I’ve hiked through the young forest on the north side of the lake, recovering slowly from the Charlton Fire that severely burned the high-elevation area. And I included the Black Creek trail, leading from the west side of the Waldo Lake Wilderness through diverse forests to the edge of the lake, in my ancient forest hiking guide.

I’m not the only one. The natural beauty and diversity of the area, and relative accessibility from major roads and nearby communities has made Waldo Lake and its watershed a popular (and booming) recreation destination – from mountain biking to backpacking to paddling.

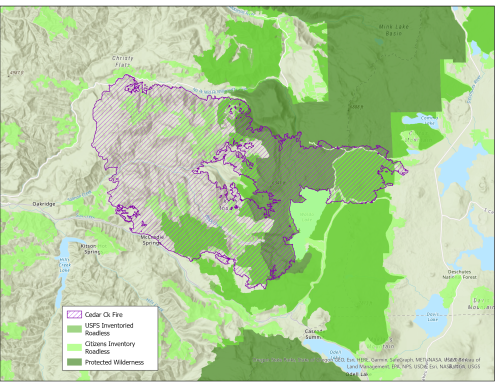

Initial protection efforts for the area were driven by the urge to safeguard the unique and pristine waters of Waldo Lake, but efforts to protect the wild and diverse forests surrounding the lake were also active. The Waldo Lake Wilderness was established in 1984, and subsequent codifications of the Roadless Rule ensured even more wild lands in this spectacular landscape had protections from logging and road building – though much had already fragmented the surrounding Willamette National Forest. The North Fork Middle Fork Willamette River – from its source on the north end of Waldo Lake downstream 42 miles – was designated as a Wild & Scenic River in 1988. Superlatives abound.

Fire has been no stranger in this rugged and diverse landscape. Historic fires shaped the high-elevation subalpine forests around Waldo Lake and the moist Douglas-fir, hemlock, and cedar forests downstream in the North Fork Middle Fork and Salt Creek watersheds for millennia. In recent years, the Warner Creek Fire burned the area around Bunchgrass Ridge in 1991 (sparking a protest and movement against post-fire logging), the 1996 Charlton Fire burned the north side of Waldo Lake, and several other small lightening-caused fires have burned in patches all around. These fires left natural legacies behind – charred snags, down logs, and remnant living trees – to form the base for rebuilding soil, wildlife habitat, and the next forest generation.

When a lightning strike started a fire on Koch Mountain on August 1, 2022, near the headwaters of Black Creek on the west side of the lake, of course I paid attention. On August 6, I watched smoke rise from where I camped with my family, and wondered what would happen to some of my favorite places and trails.

The fire burned in the steep terrain on the edge of the Wilderness for a few weeks. Firefighters were cautious in the steep terrain, and sensitive to the wild landscape and ecosystem. The fire might well have fizzled out without reaching the lake or threatening nearby Oakridge were it not for a strong wind event at the peak of the hot, dry summer, which drove the fire north and east across the old Charlton burn, then west towards town – encompassing the Warner Creek fire area as well. In the end, the Cedar Creek fire impacted 127,000 acres, (including areas intentionally burned by firefighters to control the fire’s spread).

I didn’t get a chance to see the fire’s aftermath until nearly a year later. In July, I arranged a flight with LightHawk – a non-profit organization that pairs volunteer pilots with conservation groups – and my colleague Tim Ingalsbee with FUSEE (Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology).

Tim is hardly a stranger to this landscape. He was one of the protesters who stopped planned post-fire logging in the Warner Creek Fire area, and he has a long history of activism promoting natural fire recovery and sound fire policy. He was interested to see the effects of this fire on the Warner Creek area so near and dear to his heart.

Michael Sherman with Spring Fed Media also joined us to document the flight. (See linked videos below)

What we saw was emotional. On the way, we flew over the Holiday Farm Fire area in the McKenzie watershed. Much of that fire burned over private industrial timber lands, where young plantations burned fast and hot, and where any burned trees still standing were logged as soon as possible. The landscape was stark – while fire impacts from this 2020 fire are quite visible, the impacts of industrial clearcutting and roads on the landscape takes it to a new level.

Once over the Willamette National Forest and the fresher Cedar Creek Fire, emotions shifted to the places I knew and loved. There was the outlet of the North Fork Middle Fork River, and the Charlton Fire – many of the legacies from 25 years ago turned to ash and the small recovering trees largely gone. There was the North Waldo Campground, where I started my first solo backpack trip in 2021 – with many burned trees but still clear blue water. And there, the Black Creek Canyon – a clear mix of fire severity, even where the fire burned for weeks, old-growth trees still green and standing tall. Over Bunchgrass Ridge, where the Warner Creek Fire burned, some of the young trees – regrowing for the past 20 years – with nothing left but their small trunks, while snags from the first fire still stand sentinel for this next round of regrowth.

As we flew toward Oakridge, smoke from the recently-started Bedrock Fire in a nearby drainage was smothering the low-elevation hills and obscuring our view.

A few months later, I finally had the chance to drive up into part of the fire area to get a closer view. The story on the ground was also one of a mix of burn severity and impact. Some areas were completely blackened – thin-barked mountain hemlock and fir trees were but standing husks, old snags and down logs converted to charcoal to feed the soil. There were also plenty of green patches that the fire didn’t touch, providing seed sources and shade for nearby burned areas.

I also saw up-close what firefighting efforts can do on the ground and the limits to human intervention and prediction in these forces of nature: swaths of forest bulldozed as a fire line – sometimes clearly adjacent to the fire (or intentionally burned to reduce fuels – a common tactic) but others surrounded by green where the fire didn’t touch. Unfortunately, these activities left unnatural scars on the landscape.

The Willamette National Forest is not planning a massive post-fire logging operation in the Cedar Creek fire area. But some roadside tree removal is proposed, and I made note of burned old-growth trees – legacies for the next generation of forest – that might be in the path of such logging. We’ll be watching proposals here carefully, urging the Forest Service to only do what is necessary, and to preserve forest legacies across this landscape.

What I saw from the air and the ground affirmed what I know about fire ecology from years of study and observation. Standing dead and downed trees are hanging on to the majority of the carbon they stored over many years, fresh growth is already coming back to become forage for deer and elk, birds and other wildlife are still using the burned areas, and there is added diversity in vegetation and forest structures.

What I saw also affirmed what I know about the importance of public lands. In the protected areas surrounding Waldo Lake, and within the bounds of Willamette National Forest, there is an opportunity for natural recovery of this burned landscape – standing in stark contrast to the private industrial lands where legacies were stripped away to move forward with another tree crop.

We can’t log our way out of fires like this. We can’t even fight our way out of fires. We’ve seen again and again that fuel breaks and fire lines in the backcountry can’t stop wind-driven fire events. What we can do is address climate change and the conditions that drive hotter, dryer summers, stress native vegetation, and lead to bigger, more severe fires.

We can also prepare our communities for the reality of climate-driven fires, investing in safe shelters and reducing the chances of home ignitions through home hardening and reducing fuels close to homes. As the state moves forwards with landscape level strategies for addressing fire risk, funding needs to be directed to real solutions – for the climate and for communities.