Eugene, Ore. (January 2026)

Contact for more information

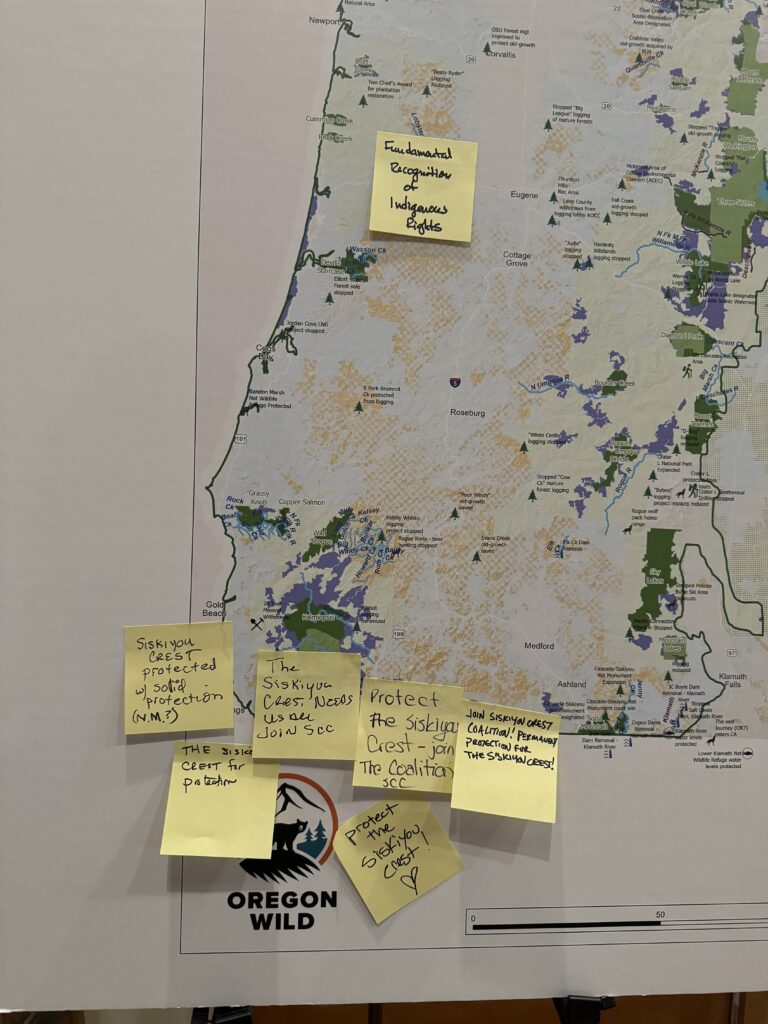

Oregon Wild today released a new report outlining risks to Oregon’s public lands, driven primarily by the Trump administration’s policies to maximize extractive industries like logging and mining. Reviewing the first year of Trump’s second term, the report entitled “Trump 2.0: Looting Oregon’s Treasures” details substantive shifts in public policy that threaten to fundamentally change the management of some of the state’s most iconic places, from the Coast Range to the Blue Mountains, the slopes of Mount Hood to the redwood forests in Southwest Oregon.

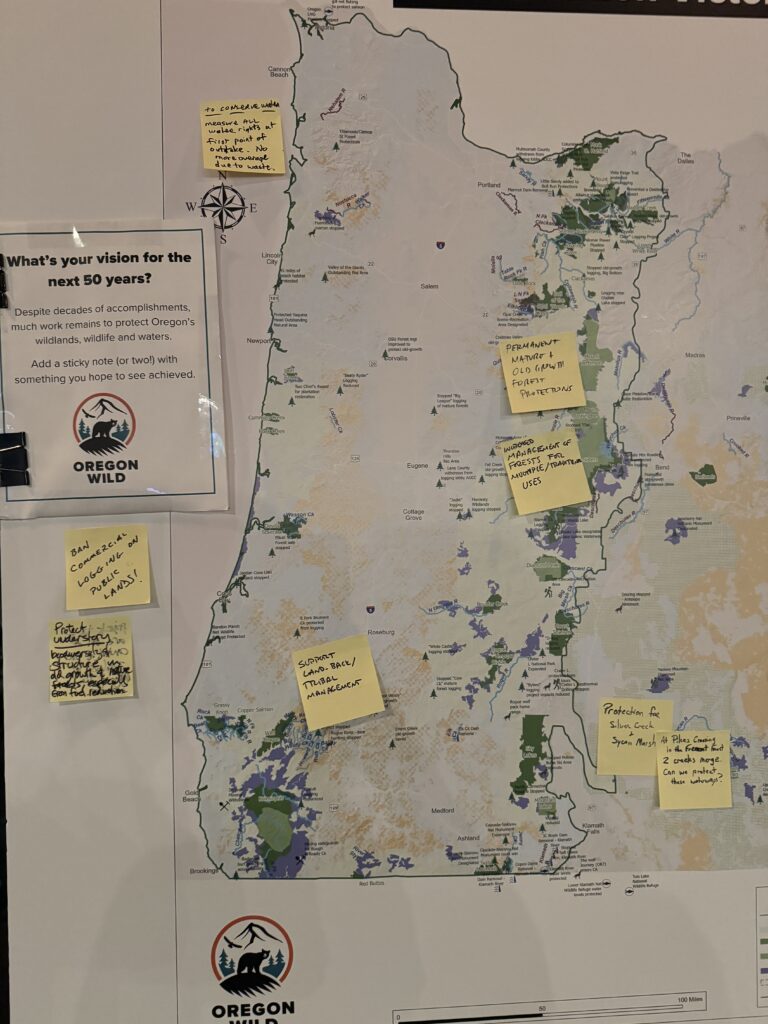

The report catalogues numerous proposed and implemented changes: revisions to the Northwest Forest Plan and Blue Mountains Forest Plan, the rescission of the National Roadless Area Conservation Rule, weakening of wildlife and habitat protections, reduced staffing and reorganization at federal management agencies, Executive Orders deregulating logging and energy development, and many more. Included are several legislative proposals, such as the Fix Our Forests Act and proposals for public lands sales.

“The Trump administration is systematically dismantling the safeguards that protect our public lands, transparency, and accountability,” said Chandra LeGue, Oregon Wild’s Senior Conservation Advocate. “This report shows exactly how those decisions translate into real harm on the ground, in places that belong to all of us.”

In addition to laying out threats to our public lands, Trump 2.0: Looting Oregon’s Treasures profiles locations many Oregonians are familiar with and illustrates how the actions of the Trump administration and Congress might impact them specifically. Through the lens of some of the places like the Oregon Dunes, Newberry Caldera, and Lost Lake on Mount Hood, the report outlines how proposals will drastically change management on the ground, limit the public’s ability to learn about and influence decisions on public lands, and threaten the resiliency of these landscapes to be enjoyed by future generations.

Locations Profiled

- Mount Hebo

- Oregon Redwoods

- Rough & Ready Creek

- McKenzie River headwaters

- Tumalo Mountain

- Lookout Mountain

- Joseph Canyon

- Oregon Dunes

- Mount Hebo

- Lost Lake

The report also details laws and policies that could protect these special places, and others across Oregon and the US. It also features suggested excursions to help Oregonians who have not yet experienced these public lands learn what is at stake.

Photo credits: Lost Lake by TJ Thorne | Joseph Canyon by David Mildrexler | Newberry Crater by Mark Darnell | Oregon Dunes by Micah Lynn

###