Last weekend, I hiked to Aneroid Lake, deep in the Eagle Cap Wilderness in Northeast Oregon. Our hike started at the busy Wallowa Lake–its cabins, lodges, and campgrounds full of families enjoying the holiday weekend and last days of summer. A couple of miles and a few switchbacks later, we were high above the lake and crossing into the Eagle Cap Wilderness. We came across several other hikers and backpackers on the trail, but the quietness was noticeable. As we caught our breath, we marveled at the immense walls of granite towering above us. Songbirds called out and darted between the firs and hemlocks. The sudden snap of a downed branch quickly drew our attention; a moment later, a deer walked out into a lush meadow, framed by stands of lodgepole and the peaks above.

At the lake, we enjoyed a charcuterie lunch on a beach to ourselves and spent the afternoon fishing for trout eager to sample anything floating on the surface. During the hike up, and especially as we lounged and fished at this scenic alpine lake, I kept thinking back to the law that permanently protected this place and many others like it. A law written and passed by forward-thinkers who believed our few remaining wild and undeveloped landscapes should be set aside and safeguarded from the ever-encroaching reach of development and extraction. It was fitting that just days before the 60th birthday of the Wilderness Act, I was visiting Oregon’s largest, and one of its first, designated wilderness areas.

The Wilderness Act is signed

On September 3, 1964–60 years ago today–President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act of 1964 into law, officially creating the National Wilderness Preservation System. With the stroke of a pen, nine Wilderness areas in Oregon, including the Eagle Cap, were designated–and many more across the U.S.

Oregon’s Wilderness Expansion: A Landmark Achievement

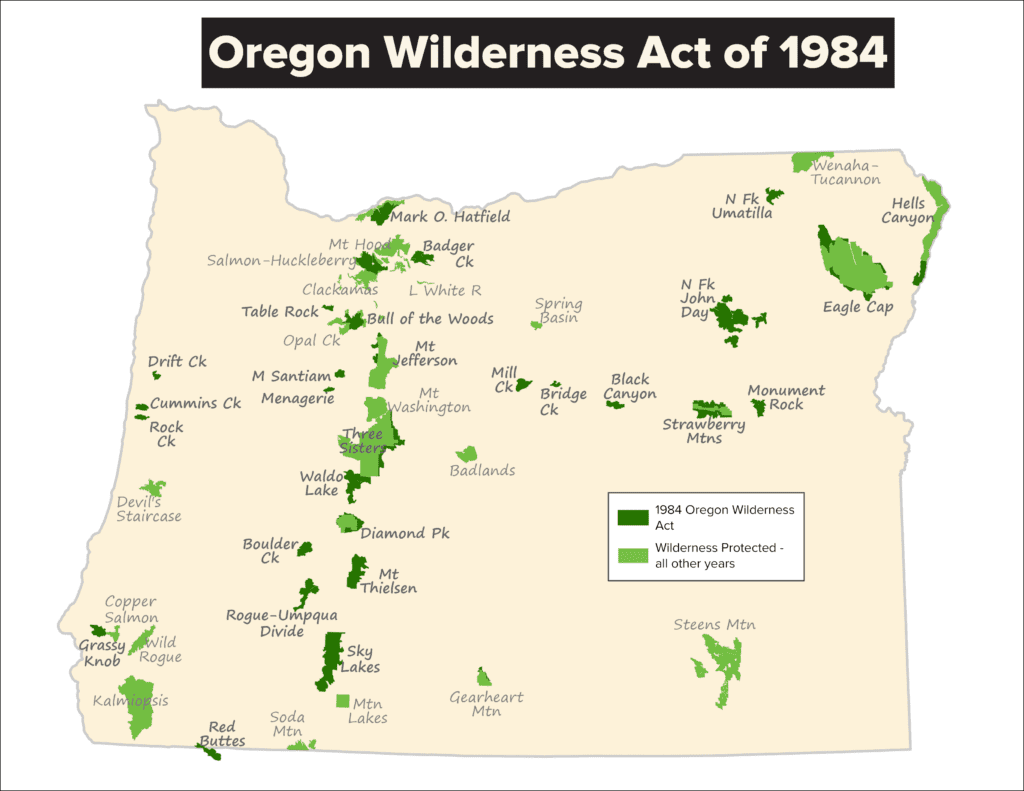

And then 40 years ago, in 1984, Oregon’s largest expansion of wilderness protections was enacted when the Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 was passed in Congress. This added 21 new wilderness areas to Oregon and expanded eight others. These newly protected areas included ecologically vital habitats like the old-growth forests of the Badger Creek, Bull of the Woods, Drift Creek, and Middle Santiam Wilderness areas. Other gems such as the Waldo Lake, Rogue-Umpqua Divide, and Mount Thielsen Wilderness areas were also established. In total, this bill added 878,000 acres of ecologically important Oregon watersheds to the Wilderness system in Oregon.

to Oregon and expanded eight others.

The Gold Standard: Why Wilderness Protection Matters

At Oregon Wild, we often refer to Wilderness designation as the “gold standard” for public lands protections, meaning it is the highest and strongest level of protection we can provide. While there are many other designations and levels of protection for our public lands, we strive for Wilderness because that is the most effective and time-tested tool available to protect natural and ecological values in our state’s wildest and most special places. Wilderness prohibits logging, development, new commercial mining, oil and gas extraction, and motorized recreation. It allows many different low-impact forms of recreation such as hiking, hunting, fishing, camping, kayaking, rafting, trail running, bird watching, skiing, snowshoeing, and more (but as Erik Fernandez, our Wilderness Program Manager, likes to say, “you just have to leave your chainsaw and bulldozer at home”).

In addition to the benefits for quiet recreation and solitude, protecting wild and undeveloped landscapes is now more important than ever as we face the impacts of the climate and biodiversity crises. Natural, wild landscapes like those found within our National Wilderness System act as carbon sinks, sequestering and storing atmospheric carbon and slowing the impacts of climate change. Oregon’s ancient forests are among the most carbon-dense in the world, storing carbon for centuries in the trunks of mature and old-growth trees and the soil. Wilderness areas also represent our most intact ecosystems–these places are free from roads and other development and activities that can degrade habitat and isolate populations. For many species, protected Wilderness is one of the last remaining refuges.

But to truly combat the rapid acceleration of climate change and biodiversity loss, we need more Wilderness. And that is especially true in Oregon.

While Oregonians are fortunate to have numerous incredible Wilderness areas in the state, only 4% of Oregon’s land mass is currently designated as protected Wilderness. This lags far behind our neighboring states of Washington (10%), California (15%), and Idaho (10%). Since that 1984 bill, only 350,000 acres of additional Wilderness have been designated in the state. Over 5 million acres of wild, forested, roadless lands in Oregon are still unprotected, and even more can be found in our desert landscapes. Beautiful and ecologically vital landscapes like the Crater Lake backcountry, Hardesty Mountain, half of the Wild Rogue, the Owyhee Canyonlands, and thousands of acres of ponderosa forests in eastern Oregon are just a few examples of our stunning yet unprotected wild lands.

Credit: David Herasimtschuck.

Oregon Wild’s Ongoing Commitment

Many who have followed along with Oregon Wild this year know that we are celebrating our own big anniversary–50 years as an organization. But many of you might not know that–before Oregon Wild and the Oregon Natural Resources Council–our original name was the Oregon Wilderness Coalition, and we worked to protect and designate Wilderness areas across the state.

Since 1974, we have played a major role in protecting our existing Wilderness areas, from the 21 Wilderness areas designated in 1984, to the Copper Salmon and expansions of Wilderness around Mount Hood in 2009, to the Devil’s Staircase in the central Coast Range in 2019–Oregon’s newest Wilderness. We are currently working to expand Wilderness protections for the Wild Rogue and Mount Hood, and we are working to pass the largest public lands and river conservation bill in Oregon history–the River Democracy Act. And we’ll never stop fighting to protect the wild in our beautiful state.

How You Can Help

But it’s time to finish the job and permanently protect these special places for good, and that’s where we need your help. In honor of these 3 big anniversaries, please consider making a gift to Oregon Wild today to support our efforts to protect Wilderness and to keep Oregon wild.