Forests and Climate

As our planet continues to warm at an unprecedented rate, the impacts on Oregon’s economy, communities, ecosystems, and our way of life will only intensify. The single biggest step Oregon can take to combat climate change is to modernize our forest management laws and protect mature and old growth forests.

In recent years, the impacts of climate change in Oregon have become more acute, including heatwaves, droughts, wildfires and severe winter storms that have impacted communities and our treasured wild places. Protecting our forests offers win-win solutions that simultaneously address the impacts we are already experiencing while also reducing the future threats of climate change.

Protect our forests from city-sized logging projects!

Tell your Senators to oppose the dangerous Fix Our Forests Act, a trojan horse for 15 square mile logging projects on our public lands!

-

How Oregon Wild works to confront climate change

- Protecting mature and old growth forests

Conserving our remaining older forests and trees on federal public lands is one of the country’s most straightforward, impactful, and cost-effective climate solutions. Oregon Wild is fighting for a strong, lasting national rule that protects mature and old growth forests from logging across federal lands as a cornerstone of US climate policy. We are a founding member of the Climate Forests Coalition. - Using nature to fight climate change

Natural climate solutions are practices that protect or enhance the ability of natural and working lands to sequester and store carbon while maintaining climate resilience, human well-being, and biodiversity. Examples include longer logging rotations in managed forests, expanding the urban tree canopy, protecting drinking watersheds, and restoring wetlands. Oregon Wild advocated for passage of one of the country’s first natural climate solutions bills as part of Oregon’s 2023 Climate Resilience Package (HB 3409). The Natural Climate Solutions Act was signed into law August 1, 2023.

- Protecting mature and old growth forests

-

Climate benefits of old-growth forests

Older trees and forests store and sequester tremendous amounts of carbon.

On the scale of an individual tree, research increasingly indicates that the rate of carbon accumulation will continue to rise as the tree grows older and larger. As a recent study concluded: “[L]arge, old trees do not act simply as senescent carbon reservoirs but actively fix large amounts of carbon compared to smaller trees; at the extreme, a single big tree can add the same amount of carbon to the forest within a year as is contained in an entire mid-sized tree.”Older forests and trees help counter the biodiversity crisis.

Forests and trees tend to develop structural complexity as they age (more hollows in trees, more snags and downed logs in forests, for example). This complexity fosters biodiversity and can support species that have specific habitat needs. For instance, older forests and trees in the West provide critical habitat for wildlife, such as pileated woodpeckers and bears.Intact forests reduce the risk of flooding, erosion, and landslides.

Intact forests have a positive effect on the redistribution of runoff, stabilize water table levels and retain soil moisture by altering soil permeability. These processes help stabilize slopes, prevent water and wind erosion, and regulate the transport of nutrients and sediments.Intact, older forests protect drinking water.

An analysis of 60-year records of daily streamflow from eight paired-basin experiments in Oregon revealed that the conversion of old-growth forest to Douglas-fir plantations (monoculture tree farms that are planted after clearcutting) had a major effect on summer streamflow.Older trees are often better able to withstand and recover from wildfires.

Older trees often possess features that make them more resistant to fire than younger trees, such as the thicker bark that comes with increasing age and size, and higher canopies that help limit the spread of crown fires. -

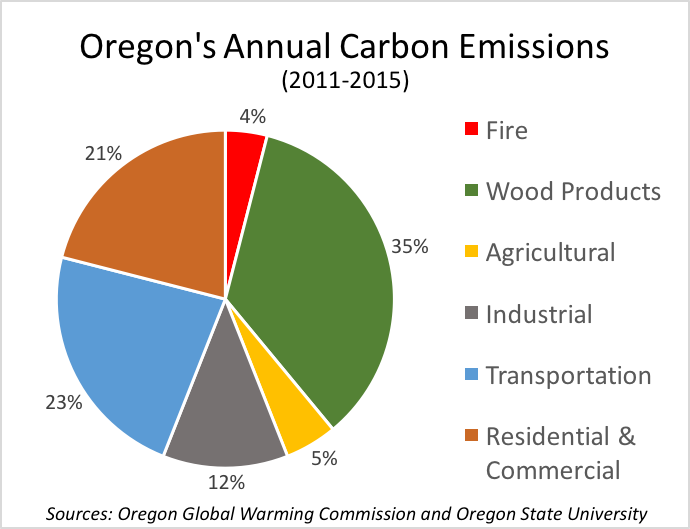

Reducing Oregon’s carbon emissions

Reducing carbon emissions from energy, transportation, manufacturing, and other industries is an important piece of the puzzle when it comes to confronting climate change and building resilience. In 2015, a groundbreaking study from Oregon State University revealed that Oregon’s logging industry is responsible for 35% of carbon emissions, more than any other sector.

Reducing emissions alone is an insufficient strategy for addressing the climate crisis we face today — the U.S. must also pull and sequester significant amounts of legacy emissions directly from the atmosphere. Therefore, we need natural climate solutions like our forests to be a central part of the effort to address climate change.

While some technologies may be able to help us meet this need in the future, our best near-term opportunities are our forests. Forests absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in trees (both living and dead), root systems, undergrowth, and in organic matter in soils. If left undisturbed, these carbon reservoirs can last centuries. Natural climate solutions, like forests, naturally remove and store atmospheric carbon.

Key Staff

- Lauren AndersonClimate Forests Program Manager

- Victoria WingellForests and Climate Campaigner