By: Marina Richie

Also a part of this series:

Saving the Big Trees of Badger Creek as Wilderness – A Lucky Break

Hardesty Mountain Roadless Area: Vigilance, Close Calls, & Heroes

Lookout Mountain: Roadless Beacon of the Ochocos

Beloved Metolius River

Every Wild Place Has a Story

It was 1979 at dawn when Bill Fleischman acted on impulse. Why not take the long way from his home in La Grande to Pendleton for the wilderness hearing? He’d hike a short way up the North Fork Umatilla River for a little fishing. What better way to get inspired to speak up for this obscure roadless area to be part of Senator Mark Hatfield’s proposed wilderness bill (a smaller-sized version before the Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984).

Sure enough, a half-mile upriver, he caught a 13-inch rainbow with extra shiny black spots. Lining his wicker creel with ferns, he lowered the wriggling fish inside and hurried back to the trailhead. The clock was ticking and he didn’t want to be late. But he would take time to clean the fish and have his catch with him at the hearing—adding a flare to his testimony. However, he had lined the creel so well the fish was still alive. That’s when things got interesting.

“I thought since the trout was fine, I’d fill the cooler with water and bring the fish along,” he said.

But when he got to the hearing, Tim Lillebo, then Oregon Wild’s eastern Oregon field representative, knew there was a problem. It’s illegal to transport a living wild trout without a permit. Problem solved: The regional director of the state wildlife agency was at the hearing and issued the permit on the spot.

With the cooler by his side, Bill used a hardhat to swirl and aerate the river water. There was muttering and speculating when he lugged the cooler up on stage to join a panel of environmentalists that he recalled included Tim, the charismatic Loren Hughes of La Grande, and Beryl Stillman from Heppner. When Bill opened the cooler lid, Senator Mark Hatfield came right down off the dais, plunged his hands into the water, and held the trout —more excited by the living fish than anything he’d heard or would hear that day. “The timber industry was so pissed off,” Bill recalled with a chuckle. After the hearing the regional director suggested he put the trout right back where he caught it. Bill did.

I got the tip about Bill and the trout from James Monteith, who spoke at that 1979 hearing, too. One of the founders of Oregon Wild and a longtime executive director, James is convinced that famous fish made a difference in securing the North Fork Umatilla within the 1984 Oregon Wilderness Act.

Taking a live trout to a wilderness hearing is brilliant. It’s also just what my friend Bill, who I’ve known since the early 1980s, would do. He’s that kind of quirky creative genius and quite a fisherman, too. While happily living in Missoula, Montana, he’s still connected to Oregon’s wilds and is a natural storyteller. Bill’s also humble, insisting his part was minor.

Enter the Legendary Marilyn Cripe

To protect the North Fork Umatilla Wilderness did take years of tenacious activism, especially from a Pendleton group called MEOW (Maintain Eastern Oregon Wilderness). What no one knew then was how critical this area would become as an anchor of a wildlife corridor and as refuge from the extreme weather of climate change.

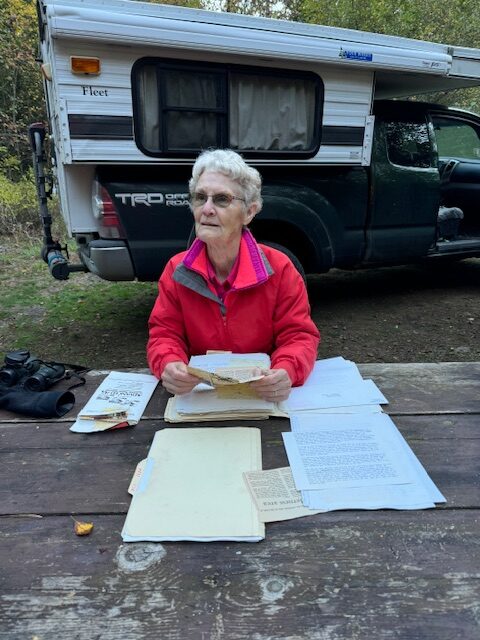

Earlier this fall, I hiked the river trail of the North Fork Umatilla Wilderness with Marilyn Cripe of Pendleton, founder of MEOW in 1970. At 82, she set a brisk pace for our group of four and only grumbled slightly about using trekking poles to prevent a fall, a concession to a setback from a stroke a year and a half earlier. I couldn’t have asked for a better guide on our six-mile round trip.

Marilyn’s passion for all things wild began in Ukiah (an hour south of Pendleton) where she rode her horse through forests from age six to nine before moving to Pendleton. Later, she and her husband Gene explored miles of backcountry on horseback. In the 1960s, they became alarmed by logging of roadless country. Soon after, Marilyn formed MEOW.

To join Marilyn is to see through her eyes the haven she’s known since first riding horseback up the precipitous Lick Creek trail with her friends the Bakers who owned the nearby Bar M Ranch. The Bakers would become fellow wilderness champions.

On this hike, we entered a wonderland of springs, maidenhair ferns, mosses and wide-bellied grand firs mingling with larch, water birch, alders cottonwoods, and Pacific yew. Wilderness enfolds the river, steep canyons, ridges, bunchgrass slopes, stringers of mixed conifer forests, and rocky rims with vast views. We followed a section of the 530-mile-long Blue Mountains Trail—created and overseen by Greater Hells Canyon Council, the grassroots group advocating for wildlands in this region.

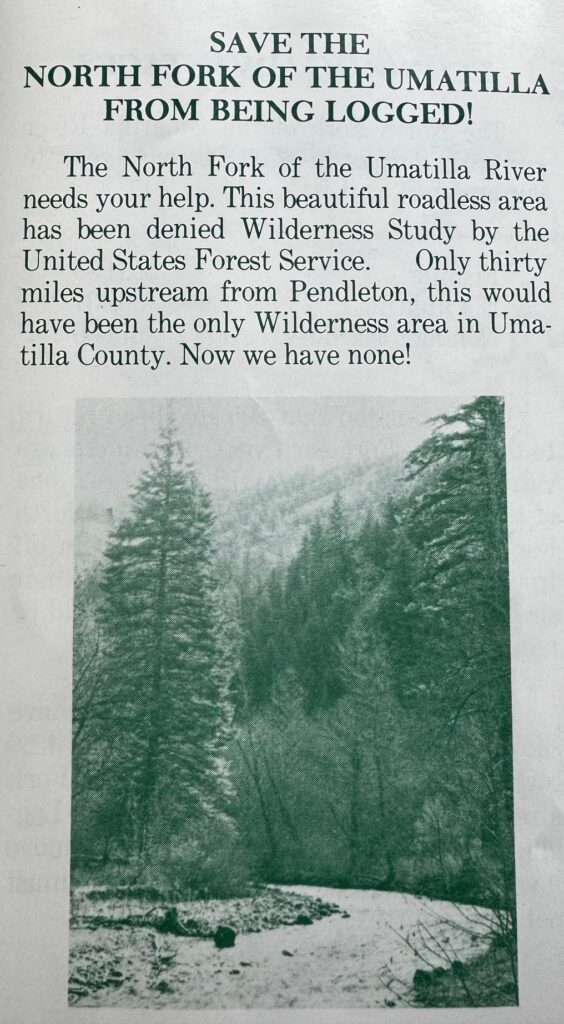

Marilyn has saved a lot of files from her days as an activist. Before our walk, Marilyn handed me a 1980 MEOW brochure with the headline in all caps, “Save the North Fork of the Umatilla From Being Logged.” Then, the Forest Service had denied Wilderness Study status, and instead tallied a potential 135 million board feet they could log from 10,000 acres—much of it steep with sensitive soils. Timber sales were in the works.

In a 1981 Wilderness hearing in La Grande, Marilyn testified on behalf of the North Fork of the John Day, Elkhorns, Lower Minam, and the North Fork of the Umatilla River. In her statement, she lamented the “coming of roads and the going of forest.” She spoke of the years she had spent studying maps, timber sales, attending meetings, hearings, and documenting roadless qualities in the field whenever she had spare time from running an electric motor service business with her husband. That’s what tenacity looks like.

On the river trail, we paused often to marvel at the log jams and channels, a beneficial aftermath of floods in February of 2020. Downed trees add nutrients and shelter for fish. Cottonwoods need flooding for seeds to sprout. Marilyn pointed to a deep pool below the log jam as ideal for an idling bull trout. A threatened species in Oregon, the trout depends on cold, clear, and connected waters. Importantly, a number of tributaries to the North Fork Umatilla, outside of protected Wilderness, are included in the River Democracy Act.

A Lush Climate Refugia and Wildlife Corridor

Forty years ago, local environmentalists recognized the high values of the pristine North Fork feeding the Umatilla River flowing through Pendleton. The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla—the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla—have intimately known and respected the life-giving Umatilla River of their homeland since time immemorial.

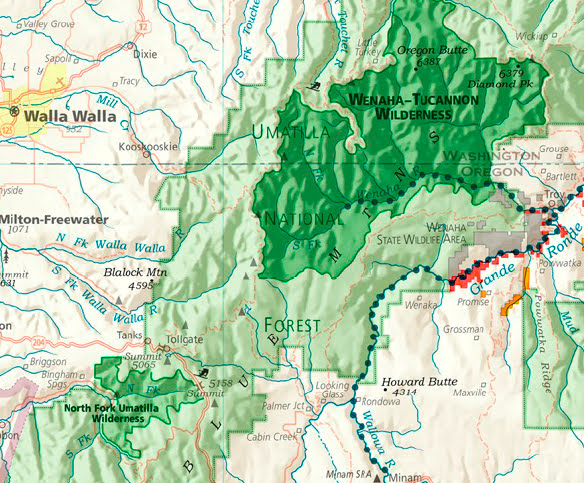

But climate change? The term was absent in 1984. Today, this verdant canyon and forests form vital climate refugia, buffering extreme weather and offering cooler realms as global temperatures rise to dangerous levels. Wildlife and even plants are on the move northward and to higher elevations—if there are ecologically intact corridors available. The North Fork Umatilla Wilderness anchors several migration routes, including a key corridor north to the Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness (177,737 acres designated in 1978). Wide-ranging animals, including wolves, elk, and cougars, traverse the linkages in multiple directions.

However, Wilderness areas across the Blue Mountains are too isolated from one another. A labyrinth of logging roads form barriers for wildlife. But add in roadless areas with strategic closing of old roads and the puzzle pieces fall in place. Permanent connectivity is possible, while in many other parts of Oregon, those pieces are missing. (To speak up for roadless areas and wildlife corridors, please weigh in on the Blue Mountains Forest Plan – see the Take Action area below.)

Return to the Rim 40 Years Later

Back in 1984, I gathered with environmentalists (including Marilyn) on the 5,000-foot elevation plateau overlooking the canyon on a snowy day. We were there to dedicate the North Fork Umatilla Wilderness. Camping the night before in Woodland Campground, we’d also hiked partway down the Nine Mile Ridge.

Returning to the Umatilla rim with Marilyn the day before our river walk, I felt the tug of connection and pride for doing my part for the 1984 Oregon Wilderness Act back in my twenties. Now as a board member of the Greater Hells Canyon Council, I’m in awe of the mostly youthful staff—motivated, smart, and the best part? They laugh often and keep up their spirits no matter how hard it gets. I see that same get-er-done and have fun spirit in Oregon Wild.

And for us folks in our “third act”? We might take a cue from the vitality of Marilyn Cripe striding up the North Fork Umatilla River trail and still speaking up for the wilds. And when it comes to that fateful 1979 wilderness hearing, I believe no testimony could compete with a gleaming trout splashing in cold, clean river water.

Take Action:

- Support the River Democracy Act: Take action here.

- Stay apprised and weigh in on the Blue Mountains Forest Plan revisions, which can have big impacts on future logging plans and protected areas. Sign up here.

Take a Hike:

- The North Fork Umatilla Wilderness is featured in Oregon’s Ancient Forests, a Hiking Guide, by Chandra LeGue, Oregon Wild (Buy it here!)

- Learn more about the Blue Mountain Trail – how to hike it, volunteer, and more!