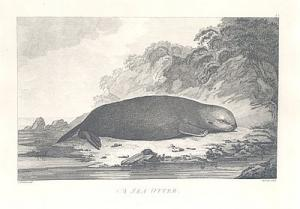

Victorian playwright Christopher Marlowe famously wrote that Helen of Troy was “the face that launched a thousand ships” and led to the epic Trojan Wars. John Webber could perhaps rightfully claim credit for having drawn a face that also inflamed the passions of men, and launched a new enterprise into the wilds off the Pacific Coast. That face, however, was not one from Greek mythology, but rather round and whiskered.

Reclining on the Nookta Sound shoreline with a bloated face and rounded body, the illustration looks more like a beached harbor seal than the lithe sea otter. But in the intricately drawn fur covering the otter, men saw fortune and empire. Like the slaughter inspired by Helen’s abduction from Sparta, Webber’s depiction of a sea otter would bring the species, and the native peoples of the Pacific Northwest, to the brink of ruin.

Webber’s illustration was included in the published journals of Captain James Cook who, sailing under the British flag, had been hunting for a pacific sea route through the Arctic that would have eased trade with Asia.- the fabled Northwest Passage. When Cook arrived on the tip of the Olympic Peninsula in what is now Washington in 1778, he described a great abundance of sea otters. Webber dutifully illustrated the opportunity.

Two other anecdotes from Cook’s voyage would spark the “fur rush” to the northwest.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES UK

The first was Cook’s claim, circulated to this day, that he had conquered scurvy. To that point, scurvy was responsible for more deaths at sea than storms, shipwrecks, combat, and all other diseases combined. The disease resulted from vitamin deficiencies, mainly C and B, and was sometimes compounded by an overdose of vitamin A from excessive seal liver – a food staple of sailors – and resulted in a grotesquerie of physical and psychological ailments, from blackened skin ulcers and loss of teeth to being overwhelmed by the senses, such that the smell of flowers wafting from shore could cause sailors to cry out in agony. Cook claimed to have conquered the disease by administering a regiment of malt, vinegar, mustard, sauerkraut, and other foodstuffs that kept the disease in check. While scholars today argue over whether Cook was successful in defeating the disease (that distinction belongs less controversially to the Scottish doctor James Lind) or was merely lucky, the claim was celebrated as fact by the British who had to that point suffered regular losses of half to two-thirds of ship crews to the disease.

The second, and perhaps even more motivating report, was that Cook had traded sea otter pelts in Canton, China for an 1800% profit. The dreams of obscene profit were so overwhelming that two of Cook’s own crew deserted to make their own fortunes.

With the promise of fortune, and threat of scurvy seemingly defeated, more expeditions were hurriedly dispatched to the Northwest. But the fur trade was as much about jockeying for territory as it was about trade.

By the time of Captain Cook’s voyages, Russia had already been engaging in the sea otter trade with China for decades, gathering furs in the far north of the Aleutian Islands and moving down the coast as the sea otter population was steadily diminished. The Russian head start, backed by the tsarist government, exhausted ready (and what were considered higher quality) otter populations and moved down the coast in the mid-1780s. The Spanish, in what is now southern California, were also trying to establish a foothold, but with a distinct disadvantage when it came to the otter pelt trade. California sea otters did not have the same dense fur as their northern neighbors, and the native tribes were less experienced in otter trapping.

The British were also trying to establish influence along the northwest. However, rather than establishing a strong sea otter trade, the British had developed a reliance on beaver and river otters. These furs were substantially less popular in China. At times, ten beaver pelts fetched the same price as one sea otter pelt in Canton. Conflicts with France and the Americans also sapped British power and influence. Increasingly, American traders or “Boston men” ended up becoming the dominant trading force in the region. American vessels ended up being cheaper to build and operate, and had faster access to their domestic ports.

While the Russians ensurfed native peoples, the Europeans and Americans treated them more like independent contractors.

Many tribes were eager to trade and lend their trapping experience in exchange for guns, alcohol, textiles, and other products. The fur trade brought increased material wealth to many of the tribes. New weapons and tools changed indigenous society from how they hunted to how they created art. Trade also integrated tribes into a complex global economy, where they began to supply other materials like salmon and timber, in addition to furs.

This prosperity was temporary.

As the fur trade intensified, and then declined as the availability of furs dwindled, tribes were drawn even further into an exploitative commercial system. The negative impact of the trade on the northwest tribes also became more evident. New diseases like smallpox and syphilis spread, as did alcoholism. Indigenous slave trading between some tribes and among settlers was exacerbated and intensified.

Peter, is the son of David Hatch, the founder of the Elakha Alliance. He inherited his father’s interest in Oregon sea otters and their relationship with the native Northwest tribes.

“A lot of Dad’s work was and his scholarship was about tracing the ways in which the health of the sea otter population and the health of Oregon’s indigenous population parallel each other very closely through the disastrous 19th century that both of us had – loss of sovereignty and loss of life. We survived and Oregon’s sea otters did not. So for us as managers, we have a sense of intergenerational responsibility for this place, we have a responsibility to do what we can to correct that wrong,” says Hatch.

Hunters and traders were so effective that by the 1820s and 30s, the northwest sea otter population was near collapse.

As Bob Bailey, Board Director of the Elakha Alliance points out, “By the middle of the 1800s, that population was down to 3000, as the Russians, British, and eventually the American fur trappers and traders hunted them out. Overnight, they were gone.”

And by 1900, the commercial fur trade had dried up for the simple fact that there were so few sea otters left to hunt.

While few pockets of sea otters remained in Alaska and southern California, here in Oregon, sea otters had been wiped out.

Danielle Moser, Wildlife Program Coordinator for Oregon Wild concludes, “Sea otters were plentiful on the Oregon coast for so long, then it was like overnight they went extinct. The last known Oregon sea otter was killed near Newport in 1906. Its pelt sold for $900.”