Of all the spectacular rivers in Oregon, it’s hard to find one as widely beloved as the McKenzie River–and for good reason. World-renowned for its fly fishing, whitewater rafting, and mountain biking, and offering endless opportunities for hiking and camping, the McKenzie River is an outdoor enthusiast’s playground. Oh, and the watershed also supplies one of Oregon’s largest population centers with clean drinking water.

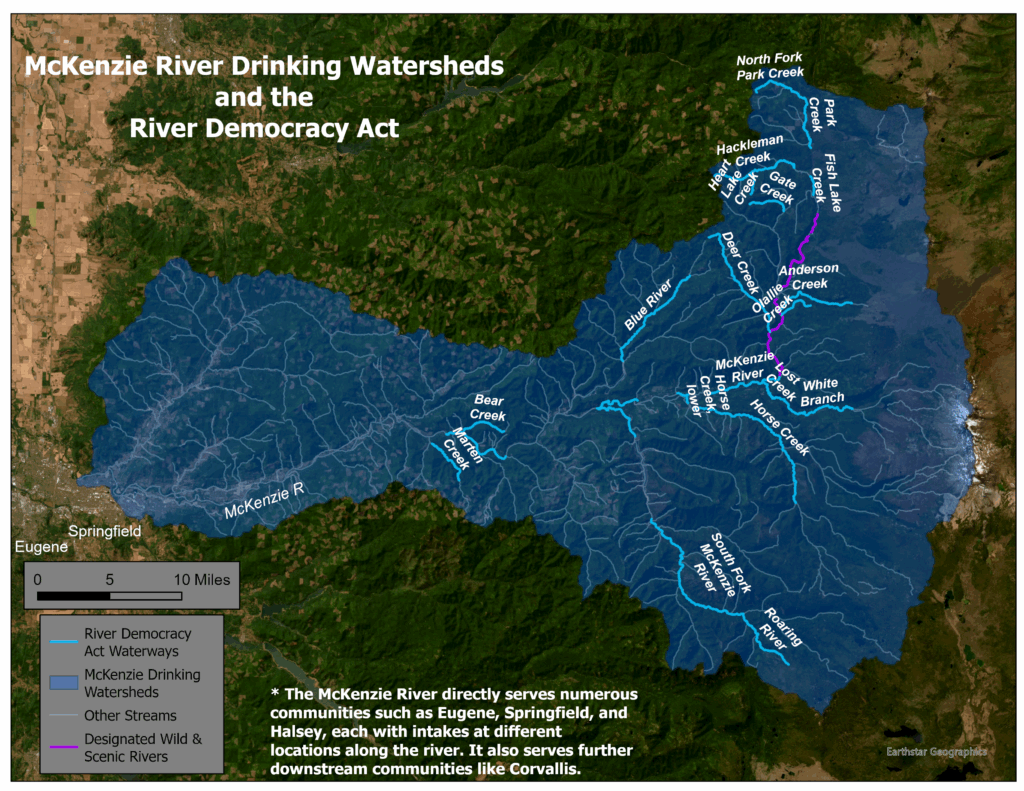

The River Democracy Act would protect these values, and more, for over 3200 miles of rivers across Oregon, including dozens within the McKenzie River basin. Read on to learn more about this key Oregon watershed and how the River Democracy Act would safeguard it and the communities that rely on it for generations to come.

Outdoor Recreation

Whether it’s rafting or fishing on the river itself, mountain biking the famous McKenzie River Trail, or enjoying the view of one of the river’s many waterfalls during a hike, there’s no shortage of outdoor adventure to be had here.

Recreation Spotlight: McKenzie River Trail

The McKenzie River Trail is a 24-mile-long trail that starts near the headwaters of the McKenzie River at Clear Lake and ends just upstream of the community of McKenzie Bridge. The trail is popular for both hiking and mountain biking.

Mountain bikers will find technical riding over sharp lava rock, flowing downhill single track through old-growth Douglas fir forests, and dazzling views of waterfalls and the aquamarine waters of the McKenzie. Most of the trail is located within the current McKenzie River Wild & Scenic corridor, but the last 5 miles of the trail is unprotected. When passed, the River Democracy Act would add protections to these last 5 miles.

Popular hikes include the 4-mile round-trip hike to Blue Pool/Tamolitch Falls and the 2.4-mile Sahalie and Koosah Falls loop.

Wildlife Habitat

The McKenzie River watershed is home to a wide variety of native species, including threatened and endangered species such as Chinook salmon and steelhead, northern spotted owls, and bulltrout.

Wildlife Spotlight: Bull Trout

Bull trout, like many other members of the salmonid family, begin their lives in cold, clear streams, feeding on small aquatic invertebrates. As these fish mature, they either migrate out of their home stream to larger streams and rivers or lakes and reservoirs, or remain in the stream where they hatched. The migratory bull trout tend to become much larger than their resident counterparts—sometimes growing as long as 40 inches and heavier than 30 pounds. Unlike Pacific salmon species that spawn once and die, bull trout will spawn multiple times in their lifetime. Migratory bull trout may migrate multiple times between spawning streams and their large river rearing habitats. Bull trout can be recognized by their particularly large, broad head and their dark olive or brown color with lighter yellowish spots. In Oregon, bull trout were historically found in streams in the Klamath basin, the Columbia and Snake Rivers and their major tributaries, and the Willamette River and its major tributaries on the west side of the Cascades.

This threatened fish has some very specific habitat requirements, and when they aren’t met, it can be disastrous for bull trout populations. Their physiology dictates that they need cold water (no higher than 60° F) to survive, as well as for the survival of their eggs. A river environment with low silt is equally important, with a gravelly bottom and plenty of protective habitat such as overhanging brush. Unfortunately, human activities such as logging have been steadily spoiling prime bull trout habitat. Logging and road building lead to siltation in rivers, lowering stream quality and raising water temperature, both of which lower the viability of eggs and hatchlings. Other threats, such as impassable dams, sometimes keep bull trout from spawning at all. Non-native brook trout also present a threat due to competition for food. In order to ensure the survival of this sensitive fish, it’s necessary that roadless areas be maintained and the fight for clean water continues.

Drinking Water

Over 200,000 people living in the Eugene-Springfield area rely on the McKenzie watershed for clean drinking water.

Intact, forested watersheds, especially those flowing through public lands, play a critical role in ensuring the quality and quantity of our water sources. These natural ecosystems act as invaluable sponges, absorbing, filtering, and gradually releasing water, contributing to the consistent flow of clean water to downstream communities.

The McKenzie River watershed is an excellent example of this natural phenomenon in action. At its headwaters, snowmelt, glacial thaw, and underground springs merge to form the mountain streams that feed the McKenzie. These streams flow through designated Wilderness areas, Roadless Areas, and mature and old-growth forests, depositing consistent, cold, clean water into the mainstem McKenzie River.

On the other hand, researchers have documented a direct correlation between industrial logging and increased flooding and peak flows. Without a healthy forest ecosystem in place to absorb and slow the release of water, rain and melting snow tend to run off of heavily logged forests much faster. That run-off causes erosion, carrying with it large quantities of sediment and debris that reduce water quality and can cause problems for water filtration systems and fish habitat further downstream.

The quick run-off during winter and spring storms also means there is less water available during the dry summer months when water demand is higher and supplies are lower. Oregon State University scientists have found that clear-cut plantation forestry can reduce water levels during summer months by 50% when compared to adjacent, unlogged old-growth watersheds.

Threats to this watershed

Despite the importance of intact, mature and old-growth forests for outdoor recreation, wildlife habitat, and clean drinking water, much of the forests in the McKenzie River watershed have been heavily logged and remain open to logging.

Aggressive commercial logging projects, such as the planned (and withdrawn) Flat Country timber sale, pose a significant threat to the mature forests and headwater streams of this area and all the important values they provide.

The Flat Country sale was withdrawn due to widespread public opposition and potential devastating environmental impacts. This project would have logged 1,000 acres of trees between 98-170 years old within the vicinity of important McKenzie watershed headwater streams such as Anderson Creek and Olallie Creek. Without permanent protections, these forests and streams remain at risk.

The Trump Administration has also recently announced that it aims to roll back the 2001 Roadless Rule, jeopardizing 58 million acres of intact, backcountry National Forest lands. In Oregon, the rule protects nearly 2 million acres of Oregon’s forests from destructive logging, road building, and development. In the McKenzie watershed, this includes thousands of acres of wild, old-growth forest surrounding the river’s headwaters.

The River Democracy Act

The River Democracy Act, co-sponsored by Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, would designate dozens of miles of the McKenzie River and other important tributaries in the watershed as Wild & Scenic Rivers, providing additional safeguards for water quality, fish and wildlife habitat, and backcountry recreation opportunities.

Streams in the watershed proposed for protection include the 15 miles of the mainstem McKenzie River, the South Fork McKenzie River, Blue River, Horse Creek, Lost Creek, Deer Creek, Olallie Creek, and Anderson Creek.

Destructive activities like mining and dam building are prohibited in and along Wild & Scenic Rivers, and other projects like commercial logging and road-building that negatively impact the landscape are tightly regulated so as to not degrade the river and river values. The River Democracy Act extends these safeguards a half-mile from each river bank, offering enhanced protections for critical waterways.

Take Action

The River Democracy Act is currently making its way through Congress, but it needs your help getting across the finish line! Take action today and help protect the McKenzie River watershed and hundreds of other Oregon waterways by signing on as a Citizen Co-sponsor and urging your members of Congress to pass the River Democracy Act!