By: Marina Richie

Also a part of this series:

Hardesty Mountain Roadless Area: Vigilance, Close Calls, & Heroes

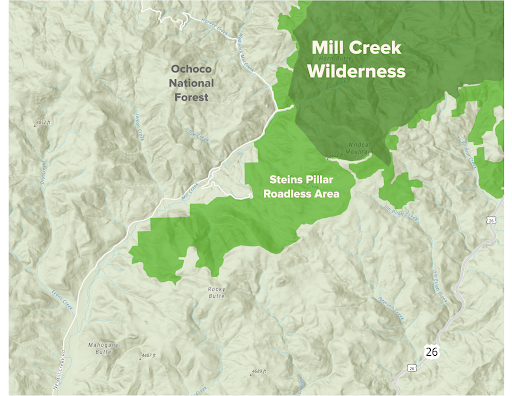

Lookout Mountain: Roadless Beacon of the Ochocos

Beloved Metolius River

Every Wild Place Has a Story

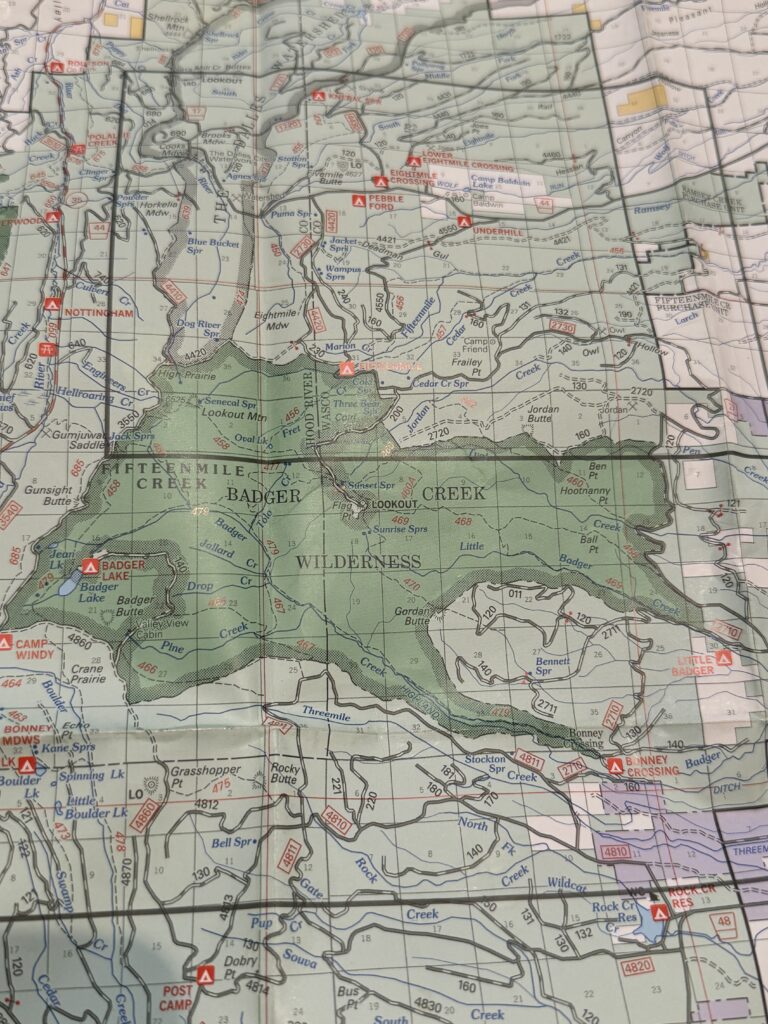

Puckery sweet huckleberries lined the upper Badger Creek trail within easy reach. Ancient western red cedars flared branches like bird wings. Noble firs, Douglas-firs, and silver firs rose columnar and elegant among Engelmann spruce, western white pine, and mountain and western hemlocks. A Pacific wren dueted with a silvery stream. Badger Creek Wilderness, at 29,000 acres, protects many centuries-old trees and ecosystems of breathtaking diversity.

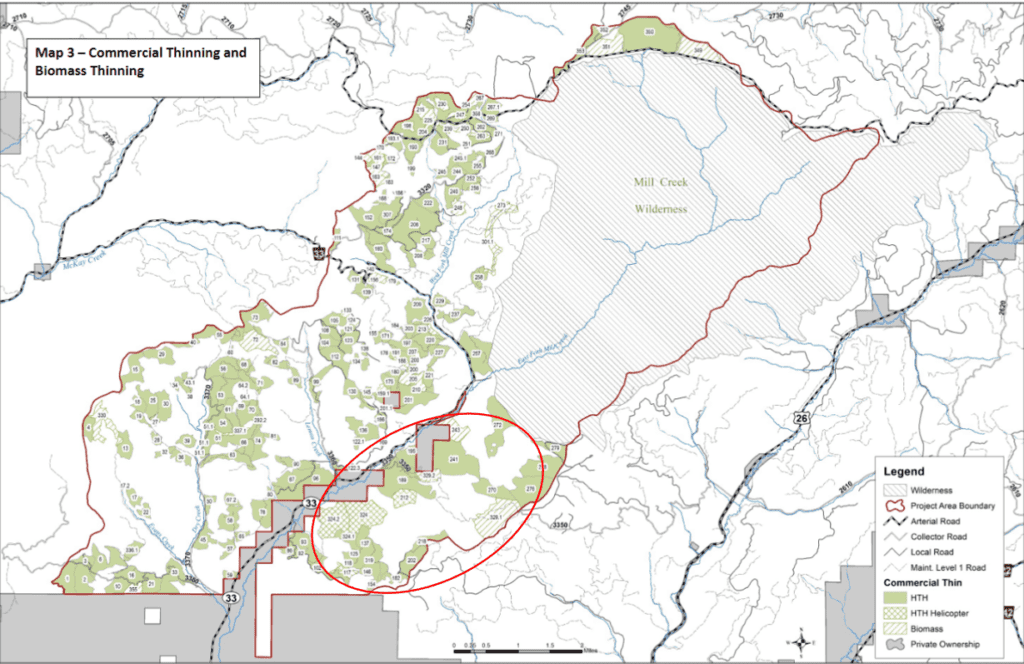

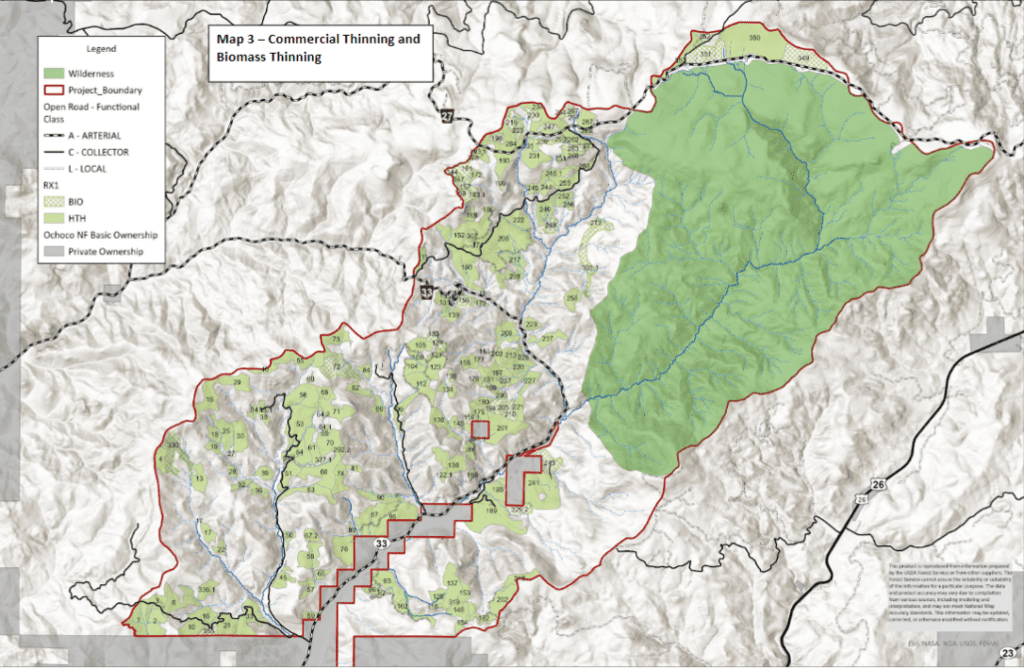

Chandra LeGue of Oregon Wild and I backpacked a round trip of 22 miles following Badger Creek to Badger Lake in early August, starting by the Bonney Crossing Campground on the eastern flank of the Mt. Hood National Forest. In our steady upward trek, beginning among white oak and ponderosas at 2,100 feet to Badger Lake at 4,400, we recorded 23 kinds of trees. It’s rare to hike within an intact canyon harboring immense trees. Thanks to Wilderness protection, Badger Creek is safe from the logging that has decimated so many low-elevation watersheds in Oregon and is still proposed (such as in the nearby Grasshopper Project).

Later, I would learn of one lucky break that likely made a key difference in Badger Creek’s inclusion in the Oregon Wilderness Bill of 1984. That story of a fateful aerial flight came from Dave Corkran, who volunteered on the Mt. Hood Forest Study Group (no longer active) and lives in Portland with his wife Char. A beloved history teacher at Portland’s private Catlin Gabel High School for 35 years, his environmental passion remains strong at age 89.

My phone call with Dave skimmed the surface of his lifetime engaged with the wilds—from surveying potential wilderness areas in Wyoming and Montana after passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act to fighting to save the Bull Run watershed (Portland’s drinking water) from logging. And yes, he knows the Badger Creek Wilderness.

“Have you been to the top of Lookout Mountain?” he asked, evoking that spectacular 360-degree view of Mt. Hood, St. Helens, Rainier, Jefferson, Adams, and Three-Fingered Jack from the 6525-foot-high summit. I admitted I had not—at least yet.

“Ruth and Ken Love were the most interested in our group in saving Badger Creek,” he said. The couple coauthored a Guide to Trails of Badger Creek, 92 pages of detailed hikes and a list of birds, butterflies, and lichens. The Portland couple founded a member group of Oregon Wilderness Coalition (OWC), the original name of today’s Oregon Wild. The Badger Creek Association consisted of themselves—Ruth and Ken. But size didn’t matter. OWC encouraged people passionate about specific wild areas to form a group and grow the coalition. The same tactic works today. There’s power in naming wild places under threat.

The story Dave would tell me about Ken’s flight over the proposed Badger Creek Wilderness with Representative Les AuCoin is one I’m betting few people have heard. If Ken were alive today (he passed in 2021), I think he’d be pleased more people know of this fortunate day. The flight was part of a successful effort by the Mt. Hood Forest Study Group to get the attention of politicians reluctant to clash with the timber industry.

“We finally persuaded Senator Mark Hatfield and Congressman Les AuCoin to look at all proposed wilderness areas around Mt Hood,” Dave said.

I imagine the small plane, miniscule beneath Mt. Hood, veering eastward. Representative AuCoin strained to hear Ken’s words above the noise of the propellers. Perhaps he was extolling the wild forests fed by three main creeks—Badger, Little Badger, and Tygh. He pointed to favorite peaks and trails. But the savvy legislator registered something else. He saw where the plane was heading—east to a treeless landscape somewhere toward Dufur.

“So instead of looking at the timber below him, he saw all that country without trees and figured this place wouldn’t impinge on logging,” Dave said. I heard him chuckling and could picture him shaking his head in amusement. He knew Ken hadn’t meant to give the congressman that impression, but that’s what Les AuCoin took away.

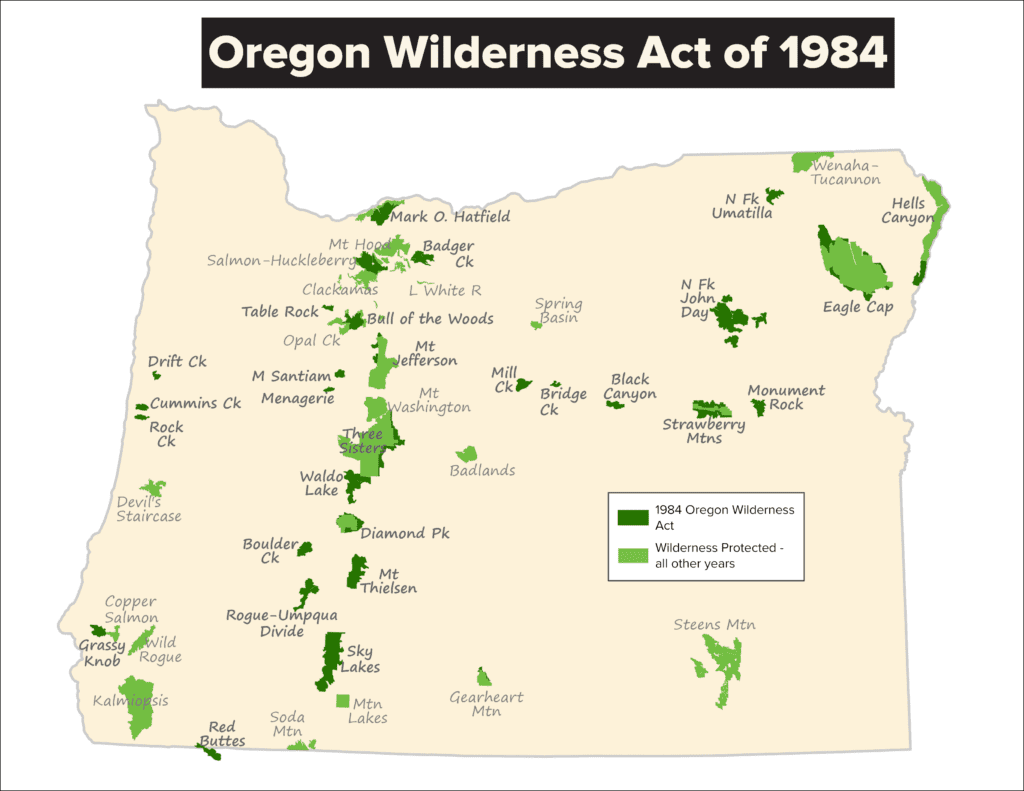

The final version of the 1984 bill included old growth forests in the Mt. Hood area in Badger Creek Wilderness as well as Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness (44,600 acres). Oregon Wild and its long list of coalition members achieved a significant victory statewide—adding 21 new Wilderness areas and expanding eight existing ones. Every one of those areas has a story of people championing the places they loved. The 1984 Act added more than 860,000 acres to the Wilderness preservation system in Oregon. Today, the state total is almost 2.2 million acres.—with 350,000 acres added since 1984.

Before my conversation with Dave Corkran ended, I couldn’t resist asking him if he’d known Brock Evans, the legendary eco-warrior hired by Dave Brower in 1967 as the Sierra Club’s Pacific Northwest field representative— and still active as a board member of Greater Hells Canyon Council from his home in La Grande.

“Yes! We all knew him. Brock organized us,” said Dave. “He’d say, ‘draw a line around the roadless area. Start agitating for the area to be set aside. Draw a line. That was his message to us. Draw a line! So, we did.”

Wild areas are far more than lines on the map. They are headwaters of drinking watersheds, strongholds for great forests capturing and storing massive amounts of carbon, havens for biodiversity, corridors for wildlife, and sanctuaries for the human spirit.

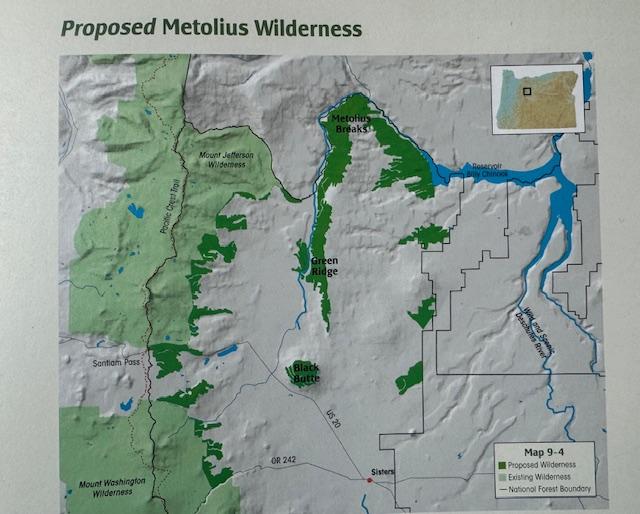

Draw a line….Trace the wilderness boundaries on a map with your finger. Celebrate Wilderness—the green protected places free from roads, logging, and all that is motorized. And then? Draw the lines around Oregon’s more than five million acres of roadless wilds on national forests. Name them. Agitate for them. In this year of decade anniversaries—60 for the Wilderness Act, 50 for Oregon Wild, and 40 for the Oregon Wilderness Act—there’s no better time than now to pull out the maps and dream big.

It’s never been easy to save Wilderness. To keep up our spirits and remember why it’s all worth it I believe in revitalizing our spirits often. Dip into the wilds near and far. Closing my eyes, I am back on the Badger Creek trail picking huckleberries until my fingers stain purple. I kneel to notice the low-down way of vanilla leaf and twinflower. Run my fingers over ferns like feathers and into icy spring water trickling by a tipped-up tree root of a great fallen fir. Spread my arms wide around the buttressed trunk of a western redcedar. Watch bats fluttering among larch, fir, and pines before I zip open my tent beside Gumjuwac Creek, flowing under great downed trees to a confluence with Badger Creek.

I give gratitude to all that shapes wild forests and is so often misunderstood—fungi, budworm, mistletoe, beetle, ant, fire, and trees packed tight together in their way of companionship. Huckleberries sweeten every thought. Abundance. Generosity. What is the way of reciprocity? Draw a line. Honor the legacy of those who came before us. Learn from our elders. Save the wilds.

Take Action: Comments on the national old-growth protection amendment are due Friday, September 20. Add your voice now! And stay tuned for ways to weigh in on proposed changes to the Northwest Forest Plan that will impact millions of acres of forests on our National Forests.

Additional Information

Take a Hike: Badger Creek Trail

Oregon’s Ancient Forests, a Hiking Guide, by Chandra LeGue, Oregon Wild—for several hikes in the Mt. Hood area outside of protected Wilderness, including Fifteen Mile Creek—just north of Badger Creek Wilderness. (Buy it here!)

Gumjuwac: The name originates from an early sheepherder called Gum Shoe Jack, known for tromping around in his rubber boots—or gum boots. This is not an indigenous name. Since time immemorial the Mt. Hood National Forest lands have been the home of many peoples, including the Cascade Chinook, Clackamas Chinook, Molalla, Warm Springs, and Wasco people.

Gumjuwac-Tolo Research Natural Area: Designated in 1996, the 3600 acres within the Badger Creek Wilderness Area encompass a high diversity of forest and stream ecosystems. Natural areas are tracts of wildlands that serve as prime examples of distinct natural features and ecosystems.

Badger Creek Trail to Lake – Chandra and Marina’s Tree Species list, including a few that might be considered shrubs but grew to tree size so we included them (elderberry). While we noticed orderly shifts of species by elevation (like mountain hemlocks, silver and noble firs up higher), we were struck by surprising companionships n this east-west transition zone.

- White oak

- Ponderosa pine

- Lodgepole pine

- Western white pine

- Douglas-fir

- Grand fir

- Silver fir

- Noble fir

- Western larch

- Western hemlock

- Mountain hemlock

- Western redcedar

- Engelman Spruce

- Pacific yew

- Black cottonwood

- Big leaf maple

- Alder

- Willow

- Chinquapin

- Hazelnut

- Rocky Mountain maple

- Mountain ash

- Elderberry

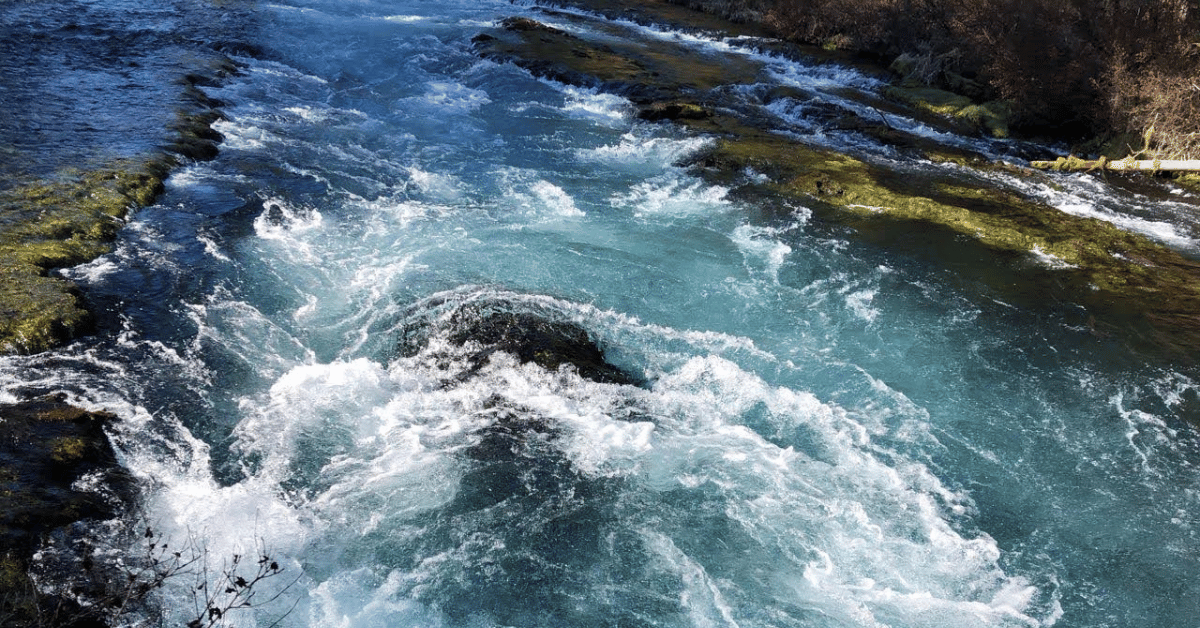

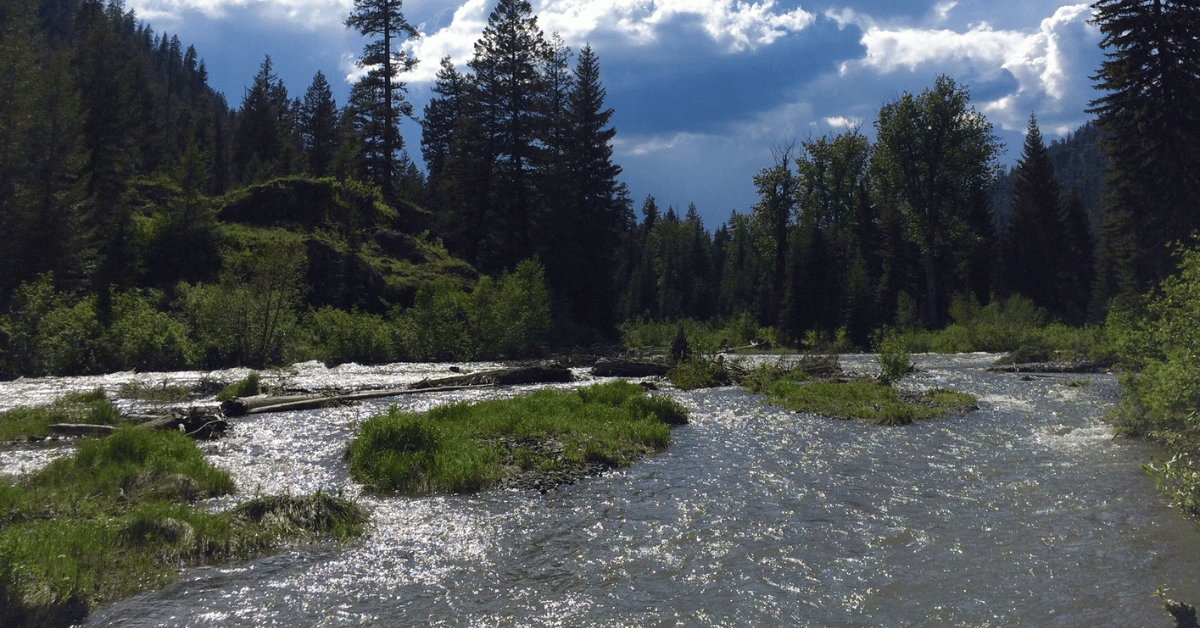

The Wild and Scenic Imnaha River

The Wild and Scenic Imnaha River